Has African Migration to the US Led to a Literary Renaissance?

Yogita Goyal Considers “Afropolitan” Literature

“For the first time, more blacks are coming to the United States from Africa than during the slave trade.” So begins Sam Roberts, chronicling recent African migrations to the United States in 2005, but suggestively framing the phenomenon by invoking the history of slavery. Implying a possible redemption of the earlier coerced movement, it is as if the voluntary migration of Africans fulfills a providential destiny, with African subjects now inhabiting, and in doing so rejuvenating, the familiar story of coming to the United States.

Noting that one in three blacks in New York City is now foreign-born, Roberts suggests that this movement “is already redefining what it means to be African-American.” In his follow-up essay from 2014, Roberts puts the figure of legal black African immigrants at one million between 2000 and 2010. He then wonders what this will mean culturally as these new immigrants identify as African or African American, and how these changing demographics will shape questions of affirmative action, reparations for slavery, and intraracial conflicts based on ethnic, religious, or linguistic differences.

That Roberts situates the issue of new African immigrants within and against the frame of Atlantic slavery is not surprising, given that most models of diaspora have tended to prioritize a similar setting. From Paul Gilroy’s focus on the memory of slavery for the descendants of a black Atlantic to frequent efforts to use Countee Cullen’s plangent query, “what is Africa to me?” as the pivot for thinking diaspora in relation to racial heritage or memory, to journeys organized around roots and return narratives, diaspora has largely been understood in relation to the African American experience.

But the Nigerian-Ghanaian writer Taiye Selasi (pictured above) tells a very different story of the migration and circulation of Africans in the world, in which the history of Atlantic slavery finds no mention: “Starting in the 1960s, the young, gifted and broke left Africa in pursuit of higher education and happiness abroad . . . Some three decades later this scattered tribe of pharmacists, physicists, physicians (and the odd polygamist) has set up camp around the globe.” As she continues, “Somewhere between the 1988 release of Coming to America and the 2001 crowning of a Nigerian Miss World, the general image of young Africans in the West transmorphed from goofy to gorgeous.”

The figure Selasi terms the “Afropolitan” refuses to choose any one place as home or to see itinerancy as tragic or alienating, insisting on multiple ways of being African. Selasi accordingly emphasizes complexity and situatedness: “To ‘be’ Nigerian is to belong to a passionate nation; to ‘be’ Yoruba, to be heir to a spiritual depth; to ‘be’ American, to ascribe to a cultural breadth; to ‘be’ British, to pass customs quickly.”

Selasi—along with such writers as Chris Abani, Chimamanda Ngozi Adichie, NoViolet Bulawayo, Teju Cole, Dinaw Mengestu, and Binyavanga Wainaina—belongs to a generation that not only heralds an African literary renaissance but also insists that new migrations demand new conceptualizations of diaspora. Most of the prominent theories of diaspora over the last two decades have been galvanized by the aspirations and contradictions of the journeys of a W. E. B. Du Bois or a Richard Wright. The new visibility of African writers is a welcome antidote to such tendencies. Yet to open up the script of diaspora itself, we still need more multifaceted histories and models of what such visibility entails or enables.

The fictions of the new African diaspora decisively shift away from existing templates of Atlantic slavery. . .

For Selasi, her blackness must be marked as different from a more visible and normative African American one: “Until I got to high school, my world consisted of white people and Nigerian people. I simply didn’t think in terms of white and black. In fact, it wasn’t even white people and Nigerian people. It was Nigerian and other.” Moreover, both her parents were disaffiliated from an African American identity: “My mother doesn’t call herself black. My father has spent his entire life as a sort of conscientious objector to American culture.”

Thus far, the figure of the contemporary African immigrant appears in this book as a refugee or child soldier, Lost Boy or kidnapped girl, seeking remedy for a subjectivity structured through trauma. For the most part, such figures experience extreme and spectacular suffering, with few scenes of ordinary life and frequent recourse to allegory and abstraction. The fictions of the new African diaspora decisively shift away from existing templates of Atlantic slavery, insisting on new frames for fathoming contemporary patterns of migration. Moreover, they reject other available prototypes—such as the ethnic bildungsroman or the immigrant plot—to funnel their stories of arrival.

In doing so, they make visible numerous critical possibilities for the study of diaspora, expanding previous geographies and weaving together race and class with location. Moving away from the concerns of previous generations—anticolonial resistance, the clash of tradition and modernity, alienation and exile—they also resist received notions of what constitutes African literature. By inviting the appreciation of varied histories and geographies of African migrations while rejecting a linear path toward immigrant assimilation in the United States, their emphasis on the varied routes of migration that have generated the new diaspora helpfully counters the hegemony of any single genealogy of blackness.

Firmly rejecting any sentimental lens through which the experiences they describe may be interpellated—whether in a humanitarian guise or a neocolonial one—these writers also rebuff models of racial formation that induct new immigrants into antiblackness. To reshape the resonant figure of the African in the West and received narratives of black difference, they illuminate hitherto marginalized histories of race by focusing on migrations other than those occasioned by the Middle Passage or Atlantic return.

To do so, they have to navigate the fraught space of Africa as an overdetermined signifier of trauma on the one hand and celebratory narratives of immigrant assimilation or triumphal globalism on the other. Available genres of sentiment, horror, or romance fall short as these writers choose to return to realism.

For the new African diaspora, the ideas of race and migration generated by Atlantic slavery no longer serve as adequate containers for black subjectivity. As Selasi puts it, “The young African immigrant must locate herself along three divides: the first between blackness and whiteness; the second within blackness, between native and foreign; the third between African and American.”

Because of such complexity, existing narratives within postcolonial or African studies must also be revised, as the traditional tendency to view locally based texts as authentic representations and those focusing on immigrant experiences as somehow less valid no longer seems applicable. That is to say, although many critics see the spectacular success of such figures as Selasi, Cole, or Adichie as somehow diluting the real African experience on the continent, such Manichean frames cannot fully account for the power of the new African narrative, which insists on thinking intermixture beyond the language of contamination or assimilation alone.

This is why despite the often middle-class protagonists at the center of these novels, we find time and again a focus on the figures that have populated this study thus far—refugees, forced migrants, and displaced and vulnerable children in the world’s largest slums. Contemporary African novels thus both rehearse and reverse the Middle Passage, prompting the question of how modern experiences of being a refugee or trafficked person or child soldier relate to the historical experience of Atlantic slavery.

The new African novel thus becomes the place where contemporary migrations are most forcefully mapped.

If the Middle Passage is understood not just historically but metaphorically and conceptually as the engine that produced African Americans (transforming a “man” into a “slave,” an “African” into a “Negro”), giving birth to the modern concept of race (indeed, the birth of modernity itself, as Morrison suggests), then does it not become available for theorizations of racial disposability in the present? How might we understand this analogy across time and place ethically—without collapsing past experiences into the present in a melancholy vein, or conflating a range of geopolitical situations into a sentimental template of a generalized global feeling?

If the first tendency is visible in the literature of neo-slavery and Afro-pessimism, and the second in the human rights construct of modern slavery, then how might we position as comparative counterpoint or complement novels like Half of a Yellow Sun, GraceLand, and We Need New Names, all of which represent civil war, military rule, and extreme poverty and inequality in the postcolony in direct relation to the United States—either literally, through immigration to the United States as escape, however incomplete or ambivalent, or through the circulation of such texts as Frederick Douglass’s Narrative of the Life of Frederick Douglass, an American Slave?

Such new migrations, as Selasi notes, are shaped by generation and demography: “Where our parents sought safety in traditional professions like doctoring, lawyering, banking, engineering, we are branching into fields like media, politics, music, venture capital, design.” And certainly, the figure of the Afropolitan may be traced in fashion, music, art, and architecture. But the stunning visibility of novelists like Adichie (whose TED Talks have made her into a household name, as her words appear in Beyoncé’s video “Flawless,” on Dior’s T-shirts, while she serves as the face of a makeup line, and New York City chooses Americanah for its 2017 One Book One New York project) clearly establishes the primacy of literary fiction rather than its often assumed demise.

The new African novel thus becomes the place where contemporary migrations are most forcefully mapped. And they do so in mostly realist fashion. Neither wildly experimental nor postmodern nor magic realist, they do what novels do best: map middle-class manners (Adichie), narrate stories of formation and education (Abani, Bulawayo, Cole), explore the possibility of romance (Adichie, Mengestu), chart social transitions (Mengestu), and probe the dysfunction of families and individuals (Cole, Selasi) with psychological depth and social intricacy.

Capturing ordinary life (as opposed to the sublime, gothic, or fantastic), these realist novels are nonetheless revisionist to their core. Whether juxtaposing the novel with the race blog, satirizing ethnographic expectations of tribal Africa, reversing the imperial romance by situating the West as the heart of darkness, or claiming the mantle of writing the great American novel, these fictions of the new diaspora fundamentally reshape the boundaries of the American, African, and African American canons alike.

__________________________________

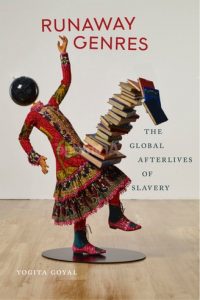

Reprinted from Runaway Genres: The Global Afterlives of Slavery by Yogita Goyal (2019) with permission from New York University Press.

Yogita Goyal

Yogita Goyal is Professor of African American Studies and English at UCLA, author of Romance, Diaspora, and the Black Atlantic Literature and the editor of the Cambridge Companion to Transnational American Literature. She edits the journal Contemporary Literature and is President of the Association for the Study of the Arts of the Present (A.S.A.P.).