It was time for reflection, Honey reflected. She would maneuver around Gordon’s assessment somehow, keep her spirits high. Their deaths would matter. They would effect, what did he call it, a paradigm shift, the earth would heal as a result of their actions, balance and beauty would return.

She decided she’d stay in the courtyard tonight, her legs were too tired to carry her to her room. She liked the courtyard, where fragments from the resort’s carefree past could still work their way up through the dirt to the surface—cribbage pegs, lanyards, confetti. You really couldn’t call it dirt anymore, least of all soil, because some worm had come through and changed its composition but the stuff was generally referred to as dirt, it being accepted that it was too much trouble to define it as something else.

She settled herself down cautiously. Heart of gold and limbs of lead and several minds directing the whole apparatus. She tried to suppress her longing to have her Cadillac back. Like a great beamy boat it had been transporting the cargo of her body. It would take her anywhere she chose to go. It was harder to get around now, even here, particularly here.

She was old now and it had taken her far too many years to arrive, but she could still pinpoint the moment when a chain of events culminated in a debt it had taken her decades to pay off. But that was what happened in a world where you were asleep and made sleepy accommodations as a dreamer would, in a dream.

The first links of the chain appeared in the semblance of a man wanting to resurface her driveway. A few hours later it was a man who wanted to repair the crack in the Caddy’s windshield. She couldn’t even see it but he detected it and offered to fix it. Someone wanted to prune her trees, hang up holiday lights. Life is too short to clean your own house, a woman told her vehemently. Lastly arrived the vendor with the fish. She was outside, then, still in her bathrobe, wondering what was killing the birds again. She had stopped feeding them, hoping the problem would resolve itself but it had not. A stumpy truck clattered up her driveway.

“Look,” she said, “I don’t even own this place. I’m renting.”

“I want to sell you some beautiful fresh fish. For supper. Join my club for a small fee and each week I’ll deliver a beautiful fish to your drawer.”

“Drawer!” she exclaimed, laughing.

“Door, door, of course,” he said irritably. He had orange hair and wore mirrored glasses.

“No, no, no. No fish. I sympathize with you having to drive around like this trying to make a few bucks but no. No fish.”

He darted around to the back of the truck and raised the door. “Look. Just look please, then decide.”

Something of the purest white with a long needle-like snout lay on a shelf from which water hung in gelid strings.

“What is that?” Honey asked. “Its head doesn’t have eyes in it. See? The real thing.”

“The real thing,” Honey said. “What is it?”

“From China, this fish. Baiji. From the Yangtze.”

“But how did it get here?”

“Truck. Refrigeration. Latest large aquatic mammal driven to extinguishment. Before that, it was, oh gee, the Caribbean monk seal in the fifties.”

Honey, in her favorite bathrobe, had never felt more vulnerable and decided on the spot that she would discontinue this swanning around in the old comfy thing of a morning.

“I wouldn’t know how to prepare it,” she said. “I’m not much of a cook.”

“Just like with anything. A little oil. Shallots if you’ve got.”

She saw her bathrobe in his glasses, a wildly cubed and patterned thing. It was as if she were a fly looking at herself.

“What if I offered this whole fish to you for two dollars.”

“Why don’t I give you two dollars and a Coke and you keep it,” Honey said quickly.

He ran his hands through his orange hair, considering.

“You know,” Honey said, “I’m a blood donor. I have an appointment this morning actually to give blood. I should have left already.”

“OK,” he said. “Two Cokes and two bucks.”

In the house she quickly changed into a long skirt, boots and several sweaters. She was very cold. She took two Cokes out of the refrigerator and a ten-dollar bill out of her purse, and hurried back outside.

He was sitting in the cab, looking impatient. “Here,” she said, “thank you very much.”

He took the offerings and looked at her disdainfully. Water shot from the truck’s bed as he accelerated away. She was driving to the Bloodmobile in her big gray Cadillac, wondering if she’d locked the house. She’d like to move away now more than ever. Sweet Jesus that fish! but as people always said, Where you gonna go? Every place is like every place else . . . What was she doing even renting a house anyway? She was a free spirit. When she’d seen that whale on the beach all carved up by drunks and pranksters she thought her life would become different but she’d just become more earthbound and maybe even more susceptible to horrid situations.

She sat mulling at a red light at a gigantic intersection. The light turned green and she floored it, she was so late, it was past actually the . . . An object smashed into the passenger door of the Cadillac, T-boning the door to a modest degree. The object, a sports car with the vanity plate MUVORER, became airborne, flying like a crumpled Kleenex into a cement utility pole by which it was trephined with glittering efficiency.

Honey was taken to the hospital for observation, though her only apparent injury was a bitten lip. Someone stole her purse as she was assisted into the ambulance but she had scissored her credit cards long before. Honey had never been able to handle the responsibilities of credit. That purse wasn’t going to get anyone anywhere.

The sports car’s driver—blatantly dead—had been the renowned commercial real estate developer Eddie Emerald, driving to close on a refugium of international significance. The elitists and extremists and anti-humanists who thought they’d secured the refugia aspects of the refugiums long ago at considerable cost and compromise found they hadn’t at all. There was a comma in a place where it wasn’t supposed to be. Or it was a comma absent from a place where it was supposed to be. The plans were still fluid as to how the properties would be utilized, but a Supercuts had shown interest in a slice of the site which comprised some stunning acreage.

The environmental community was ecstatic at the news of Eddie’s death. Eddie Emerald gone! Eddie Fucking Emerald offed by a fatty in a Caddy. Honey became as a goddess to them.

At the hospital the decision was made to keep her for observation—a week or two at the most, they said. Something was amiss with her but the doctors couldn’t determine what. She was large, but she didn’t at all look her age, which she reluctantly disclosed. She had always had good skin and being practically gigantic, everyone knew, kept you looking younger longer. You’d ask anybody to guess her age and they’d be off at the very least by ten years unless they sensed a trick and threw out a figure that wasn’t sincere.

It was when she was in the hospital that she discovered the cell in the basement, not a cell naturally with bars and a cold floor but a group of people who considered themselves a Cell. There were never more than half a dozen of them. They sat around a scarred table under bright fluorescent lights and listened to a pleasant voice emitting from a tape recorder. They didn’t believe in reality the way most people believed in it, was the nearest Honey could get to what they believed in. Though “belief ” wasn’t even the proper word. When the recording was over, the leader—she guessed he was the leader even if he seemed self-effacing to a fault—made a few comments in a soft voice. Sometimes someone would ask a question, making a stab at clarification, she supposed. Is this the same as this? Or, Don’t you think we ought to . . . The answer was always no. There was never any wine or cookies or juice. The hour was not at all companionable. Still, the meetings thrilled her in some anxious way though there was very little she could retain from the discussions. Once there was some talk about the Net. The Net holds the person who is asleep by ropes and cords and pulleys and hooks. The Net holds us fast. The Net exists even in the Underworld and the dead regard it with dismay and abhorrence. The subject of the Net was then dropped. Someone quietly remarked that a person who is not horrified by himself knows nothing of himself.

Then the Cell moved elsewhere. The room was taken over evenings by an investment seminar. No one knew where the Cell had gone or under what banner they had managed to obtain the room in the first place as it was primarily reserved for CPR instruction or lactation classes.

Honey was bereft. It was around this time that the environmental groups stopped sending flowers and grateful notes to her room because Eddie Emerald’s widow had gone ahead with the dozing and flattening of the refugium even though her legal right to do so was in doubt. The blading of the site was done the morning the scrappy developer was buried, as a final tribute to him. At the same time the mourners were enjoying post-internment cocktails and munchies at the DoubleTree, the announcement was made to whooping applause that the land was 100-percent leased out, In-N-Out-Burger, an organic farmer’s market and a car and truck detailing station were the last lucky tenants. Eddie Emerald might be gone but so was the pocket wilderness. Honey might even have accelerated its death, some activists groused. Fucking Eddie had been the devil they knew and occasionally he had tossed them a bone. And now he was no more.

The hospital was abruptly eager to discharge her. Whatever Honey had was unusual and fatal but the doctors with their poking and prodding and questioning had gotten pretty much all they could out of her without cutting her open, a suggestion she rejected, she hoped, with grace and good nature. She was susceptible to her lost basement’s Cell’s idea that self-annihilation was necessary for spiritual rebirth but she didn’t think that consigning herself into the curious hands of surgeons at this undistinguished institution was what they meant.

The nurses said goodbye, gave her the usual—the plastic pan, the bath wipes, the Sure-Grip socks, the tube of moisturizing lotion, the complimentary magazine.

“It might take you a little longer than you’d think to read these articles,” a nurse suggested. “Your comprehension might be down a bit.”

While she was waiting for a wheelchair to remove her she read about a seven-year-old who got fourteen years in the slammer for environmental activism. If she’d had even one milk tooth left in her head she wouldn’t have fallen under the terrorism enhancement sentencing guidelines but she didn’t so she had. The child’s name wasn’t being released because of her age but the journalist did provide the detail that she was no higher than a tabletop which meant that she couldn’t even attend a carnival ride unattended. But what had the poor kid done anyway? Honey couldn’t seem to extract this information from the article. “Punishing crimes in the name of the environment is our highest priority,” the successful prosecutor was quoted as saying.

The phrasing seemed wily in the extreme, but Honey feared the nurse might have a point. Her comprehension had begun to fray.

A bill was presented and at last a wheelchair was provided. In it she was pushed to the curb. She owed the place over three hundred thousand dollars which she naturally lacked the means to pay. They assured her they would hound her to the ends of the earth and beyond if necessary to collect these funds.

She had lingered outside the hospital’s doors for some time. It was eerily silent and the air smelled sharp and acrid. Nothing was particularly recognizable to her, nothing seemed suited to her nature. She walked a few yards and it became dark quickly. Then it was day again and she was cooling her swollen feet in the tepid waters of a sorry-looking lake. Yellow scum tickled her ankles. It felt nice though, no doubt about that. Her poor feet blessed her for her presence of mind in an untenable situation. The people here weren’t as intriguing as those in the Cell but they weren’t all that different from them either. They didn’t seem to be in full possession of their faculties but who was these days? She sometimes entertained the thought she’d died in her dear old Caddy and that this was death. But if that were the situation then everyone here would have to be dead as well which was possible if unlikely, even that new girl who’d shown up who seemed so familiar but who was not. And if that were the situation why were there so few of them and why were the demands being made upon them so futile given their condition? The world seemed to be proceeding as it always had, it hadn’t ended after all, which was strange too.

She’d been so discouraged once, so discouraged, and even this place could make her blue. For example, the story about the whale, the story that meant so much to her, had scarcely been acknowledged, and she was sure she hadn’t mentioned it before, which would have been tiresome she guessed.

She tried to settle down and enjoy the night which enveloped her not that comfortably, though she preferred it to the days, which mostly had a rubbery, unforgiving texture. This place was outside the perimeter of death, she assured herself. Or was it parameter she wondered . . .

_______________________________________

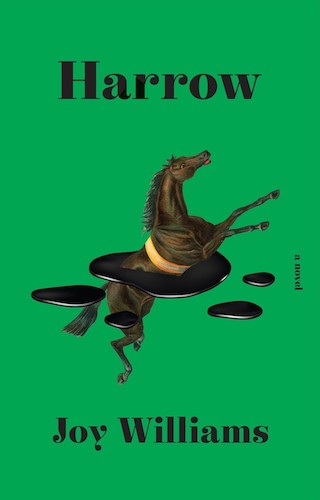

From Harrow by Joy Williams. Copyright © 2021 by Joy Williams. Excerpted with permission from Knopf Publishing Group.