Harold R. Johnson on How We Tell Our Own Stories

“We are the stories we are told and we are the stories we tell ourselves.”

We are all story. We are the stories we are told and we are the stories we tell ourselves. To change our circumstances, we need to change our story: edit it, modify it, or completely rewrite it. You have your lifestory. It’s the story you tell yourself about yourself. It’s as true as any other. If you tell yourself a story over and over again, no matter how improbable it may sound when you begin, in time the story will manifest itself.

Stories are not part of your culture. Your culture is story. It is entirely story. Everyone’s is. We are all the stories we are told. Our being is story. Our essence is story. Our vision is shaped by story; our hearing, our morals and ethics are all story. The wiring in our brains is shaped by story. Every thought you think is framed by story.

I am story.

You are story.

The universe is story, and it all comes from the Trickster.

To change our circumstances, we need to change our story.

None of the stories we tell ourselves are true. We’ve made them up. It wasn’t intentional. We simply inferred meaning into the experiences we encountered. Shortly after my birth, someone put a nipple in my mouth and squirted warm milk. At the same time, I heard sound. My brain connected the sound I was hearing with the taste of warm milk in my mouth—a neural pathway was created, and I inferred meaning to my experience. I connected the taste of my mother’s milk with the sound of her voice.

My mother’s voice was a story that meant I was cared for. As I grew, I continued to infer meaning into my experiences. Each new experience built upon previous experiences. I interpreted them, I inferred meaning into them, based upon what was already in my body of understanding. That is to say, upon previous inferences.

A child learns an amazing amount in its first years. I learned a language. I learned the rules of socialization. I learned mobility and balance. I learned to walk and talk and think. I learned things adults struggle with. I learned how to imagine, how to play, how to pretend. Each bit of learning, as I developed my understanding of who I was, where I was, and who I was related to, built upon previous understandings.

I interpreted new experiences based upon what was already in my brain, and I continued to add to that body of understanding throughout my life, through grade school, then high school, into the world of work, through marriage and parenthood, into university, and throughout my career as a lawyer and writer, and now as an Elder.

Each time I came upon new information, I inferred meaning into it based upon what I had already learned. I interpreted the world around me based upon a core body of understanding that I continuously grew.

This is different from assuming meaning. Assumptions are conclusions based upon belief. Most racist ideas are assumptions. Inferences, on the other hand, are conclusions based upon an interpretation of the evidence available—not based purely on belief.

I hope I relied, and still rely, more upon inference than I did upon assumption, but I am human and humans err. Some of what I think I know is merely assumed, based in belief, and might be wrong. But even if I didn’t make any assumptions—if my interpretation of the world around me was pure inference—it still is likely wrong. This is because the act of inferring, of interpreting experience and evidence, relies upon knowledge that is already in my mind.

Everything in my mind is a chain of inferences going all the way back to the taste of warm milk in my mouth and my mother’s voice. If anywhere along that chain, I inferred wrongly—if I interpreted an experience or evidence poorly—then everything that follows is informed by an idea that isn’t true.

Here’s an example. Early on in life I came to the conclusion that hard work was essential to my purpose. I allowed it to define who I was. Being a hard worker won me respect and accolades, which in turn reinforced my belief in the importance of hard work.

I should have figured it out while I was in the midst of it. For a time I worked one week in a remote mine camp, followed by one week at home. Except I didn’t spend the week at home. Instead, I ran a small forestry operation. I worked extremely hard. Harder than anyone I knew, and yet I lived not very far above the poverty line. Hard work on its own does not ensure success. I lost my forestry operation when Canada Revenue came after me for back taxes.

The story I have been building throughout my life is probably a fiction in more ways than one.

It’s only now, as an Elder looking back, I can see how that faulty inference diminished my life. I spent too much time working and not enough time with my family. In real terms I would have been much richer if I had not pursued economic wealth over mental, emotional, and spiritual wealth.

*

The story I have been building throughout my life is probably a fiction in more ways than one. Knowing that I inferred wrongly at times as I built the chain of inferences that make up my understanding leads me to conclude that I cannot say with any certainty that anything is true.

And neither can you.

This conclusion is liberating. If we cannot with certainty say that anything is absolutely true, then we are not bound to any single version of the story we inhabit. We are free to change our story, modify it, amend it, or completely rewrite it. We are free to adopt any story we chose.

That means there is no such thing as non-fiction. Multiple stories can be told about any event. We choose which one to tell. For example: I told you that I went to Harvard because I wanted to prove that nobody gave me anything. That’s true. But I also went to Harvard because Harvard is a prestigious place and I wanted some of that prestige. Another reason I went to Harvard was to study. I wanted to know more.

Without all of the details, and as you’ve seen with my Harvard story, when elements are missing, you only get one version of the story. When new information is added, the meaning of the story is changed.

Try to tell a completely true story of our gathering this evening. You would have to tell the thoughts of each person here. You would have to tell how they came to be here, and to tell each person’s story accurately, you would have to tell the story of each of their family members. You would have to include the fire we are sitting around, how it was started, which wood was chosen, and the story of the tree the wood came from. For the story to be complete you would have to tell the history of this place going back 4.543 billion years and the story of everything that has ever happened here.

I know that’s a bit extreme. I know what I am saying is impossible in practice. We try to tell whole stories by telling only the pertinent parts, and, out of necessity, we omit that which we consider irrelevant. But that’s the point. We choose what we leave out. Like a carver, we shave off bits and pieces until we have the image we are looking for. While the image might be the best that we can create, it is still something that we created, and a created story is the very definition of fiction.

So nothing is true.

That’s okay.

*

We are in a new age. Yeah, we are all sitting here around a fire and the sun is going down and the mosquitos are beginning to come out, and everyone has their cell phones shut off. I don’t see anyone with their head down, looking into their hands, checking the latest status updates. But even though we have put them aside for the time we are here, we are undoubtedly fully in the age of the cell phone. If you look across the lake—there—up in the hills, that red light. That’s a cellular tower. The bandwidth here is a little low, reception isn’t great, but we are covered.

With the invention of the transistor in 1947, we left behind the industrial era and entered the information age. Developments in transistor technology allowed the computer to shrink so that now your cell phone has more computing power than the computer used by NASA to put the first men on the moon. Our lives have been fundamentally and forever changed, and the change has been rapid. Consider that the Wright brothers first flew in 1903, the transistor was invented in 1947, and we landed men on the moon in 1969—only sixty-six years after we first took to the skies.

We are free to change our story, modify it, amend it, or completely rewrite it. We are free to adopt any story we chose.

We are in a new age, and we need a new story. We need a story that will tell us who we are at this time in history, that includes all the new things we have learned, that tries to be more complete and doesn’t leave anybody out. The old stories from the last age can’t tell us what we are supposed to be doing now, nor what our purpose is.

Remember that the religion story facilitated the agrarian revolution. The invention of the steam engine, coupled with the wealth pilfered from the Americas, brought about the Industrial Revolution, and a new story was required to facilitate this massive societal upheaval. We came up with two: capitalism and socialism. Despite their alleged contradiction, they are both industrial stories. Both encourage the land-based serf to leave the farm and move into the city to work in factories. Both promise to improve the life of the worker.

Capitalism, in theory, allows him to work his way up a proverbial ladder of success with a promise that with hard work and luck, he, too, can become a tycoon. Socialism promised the serf freedom to work in a factory, a decent salary, benefits, and a pension. Both the capitalist and socialist stories depend upon the exploitation of the Earth’s resources. A capitalist will cut down the last tree if there is money to be made. A socialist will cut down the last tree so long as the worker doing the cutting belongs to a trade union. They are just two of the many stories we are telling ourselves now, stories from which we derive our conscious world, our understanding of ourselves, and our understanding of our place here.

Some of our stories, like the story about rights, are so powerful that some people are prepared to kill other people to protect their interpretations of them. Rights don’t exist in nature. Rights are stories we made up. I’ve heard some pretty bizarre claims of right—the right to not wear a mask during a pandemic, the right to say horrible things about people on social media, the right to a gun. When asked where these rights come from, we often hear they came from God. They didn’t. The best claim to a right is that it exists in legislation.

The Charter of Rights and Freedoms is a beautiful story. It should win the Governor General’s Award for fiction. It’s okay. The Charter, despite its fictional nature, is the best we can do right now. When we organize our society, we can use stories about rights. They help to balance things. They only become a problem when people begin to believe that these stories we call rights are somehow fundamental, that they exist separate from us, and that they need to be defended with violence.

Another story, told by fundamentalists, is the one about evil. It’s just a story. We made it up. It exists nowhere other than in our minds. In our original Nehithaw way of understanding, everything was good and bad at the same time. We don’t get the separate concept of evil unless we create a dichotomy—when we break what we see in nature into two and make them opposites. It doesn’t do us any good to do that; it serves no useful purpose. The concept of separate good and evil drives division and conflict. It gives us something to fight against. We can name a thing or a people evil and go to war against them.

Evil does not exist in nature. Look around you. There is nothing you can point to and say, “That is evil.” A bear takes a fish, an eagle scavenges roadkill—these are natural acts, neither good nor bad. In the modern world, it is hard to say what is good and what is evil. The Aswan Dam in Egypt helped farmers irrigate, but because it reduced the nutrients that flowed down the Nile into the Mediterranean Sea, the sardine fishery fell from 18,000 tons in 1962 to 460 tons in 1968. The dam might have been good for the farmers, but it was an evil for the fishers.

People come from all across Canada to work in the tar sands. To them, employment and high wages are a good thing. To Aboriginal people living downstream and subjected to higher rates of cancer as a result, the tar sands are a death sentence. You might think that after working in the criminal justice system for two decades that I would have encountered a few evil people. I assure you I have not. I met some people who were so unhealthy they were a danger to themselves and to others, but I never met anyone I would classify as evil.

Even things we believe are absolute fact are merely the best story we can tell about ourselves right now. Science not only has its basic tenets rooted in story, it is essentially a story-generating machine. The original Christian story placed man at the center of the universe. Copernicus changed that story to one where the planet Earth orbits the sun. Newton retold the orbiting planets story to include gravity. Einstein modified the story about gravity with the story of relativity.

Quantum physics retells the story in impermanence. The Higgs-Boson story gives solidity to the impermanence. Fifty years from now, the story will change yet again when new ideas replace existing ones. Fifty years after that, the story will change yet again when even newer ideas emerge. At any given time—past, present, or future—the best science can do is to give us the most compelling story available about ourselves, our planet, and our place in the universe. No matter how compelling the story, we should know that it is not the incontrovertible truth. At some point in the future, the story, the truth we rely upon today, is going to change. It will be replaced by a new story.

That the best science can do is provide a coherent story does not diminish the validity of science. That the story is inevitably going to change in the future doesn’t change the fact that the story science provides today is the best possible story available. We can still rely upon the story science provides to make decisions while knowing the basis of our decision is only the best presently known.

The universe might exist because we have a story that says it does.

Think about it this way. I like working on old vehicles and have kept a few antiques running. When these vehicles were built, they were the best available. Then it was quite common to pull the points out of a distributor and use a bit of sandpaper to clean them up. They were easy to work on and easy to replace because they were designed to burn out.

Yeah, there was a condenser to reduce the rate of burning, but it didn’t eliminate it, and eventually you had to replace the points. Now the best available, our current, modern vehicles don’t have points. They have electronic ignition, but even that is on its way out as we move to electric vehicles and the best available is shown again to be just that: what we have right now.

Science textbooks are good collections of stories, and the subjects of scientific studies are likewise story. The universe itself is possibly made from story. We know that the foundational building blocks of all matter, even dark matter and antimatter, are made from quanta, discrete units of energy that we’ve named quarks. In their normal state, subatomic particles are in superposition until they are observed. They are in effect everywhere and nowhere at the same time. Upon observation the particle collapses to a single point. This is known as the observer effect.

If we apply the concept of the observer effect to everyday reality, then the universe exists because we are aware of it. Albert Einstein did not agree. He famously asked if that meant the moon was not there when he was not looking at it. Despite Einstein’s doubts, the evidence keeps piling up that the universe exists because it is part of our story. It’s possible that our combined consciousness generates the illusion of physical reality. The universe might exist because we have a story that says it does.

_____________________________________

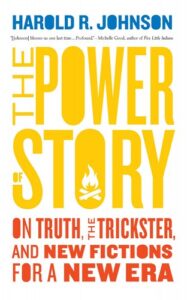

Excerpted from The Power of Story: On Truth, the Trickster, and New Fictions for a New Era by Harold R. Johnson. Copyright © 2022. Available from Biblioasis.

Harold R. Johnson

Harold R. Johnson (1954–2022) was the author of six works of fiction and six works of nonfiction, including Firewater: How Alcohol is Killing My People (and Yours), which was a finalist for the Governor General’s Literary Award for Nonfiction. Born and raised in northern Saskatchewan to a Swedish father and a Cree mother, Johnson served in the Canadian Navy and worked as a miner, logger, mechanic, trapper, fisherman, tree planter, and heavy-equipment operator. He graduated from Harvard Law School and managed a private practice for several years before becoming a Crown prosecutor. He was a member of the Montreal Lake Cree Nation.