The Beef Sometimes Begins with a Dance Move

A waltz in a circular chamber of your homies and not-homies, shouting chants of excitement. There are whole seasons where the people I grew up around didn’t want to throw fists, but might do it begrudgingly. These seasons are never to be confused with the seasons where people charge into all manner of ruckus until a playground or a basketball court is a tornado of fists and elbows and sometimes legs. In those seasons, one might have to fight once or twice just so people know they aren’t afraid to. Run the white tee through a light wash so the stain of blood might take on a copper tint when the summer sunlight spills onto it.

These seasons don’t align for everyone. Sometimes, if the hands are fresh from burial, or from planting roses on a grave, calling them to make a fist seems impossible. In school, if any sports team was relying on your presence, a teammate would likely pull you away from whatever your emotions were dragging you toward.

What I have loved and not loved about beef is that it becomes more treacherous the longer it lies dormant. When I was coming up, particularly in school, sometimes the performance of beef was in two people who didn’t particularly want to fight, inching toward each other’s faces, airing out a set of grievances ferociously, hands clenched at their sides. If you have had beef that careened toward a violent climax, you know when someone is and isn’t down to scrap. I knew if someone locked eyes with mine—unblinking and unmoving—then there wouldn’t be much of an actual physical fight to be had.

Just the performance of perceived dominance. I wish more people talked about the moments that build up to a potential brawl as intimacy. The way it begs of closeness and anticipation and yes, the eye contact, tracing the interior of a person you may hate but still try to know, even if the knowing is simply a way to keep yourself safe.

There were the real beefs of my neighborhood: over territory or someone coming back to the block with too much product or not enough cash or any long string of retaliatory violence. Those were the beefs that might end in a funeral, or a prolonged hospital stay, or a parent trembling under a porch light and yelling their child’s name down a dark street only to have the darkness lob their own voice back to them.

The secondary beefs—the ones that most consumed me and my pals growing up—were almost exclusively about the trials and tribulations of romance. Particularly when it came to the boys. Someone had a girlfriend, and then they didn’t. If someone kissed someone else outside the Lennox movie theater while we all waited to be picked up by parents on a Friday night, by Sunday, who knows what the perceived slight could be built up into. This was the era before widespread cellphone use among teenagers, before camera phones and the boom of the Internet. Everything seen was passed along in a slow chain of information, the story being accessorized with salacious details as it bounced from one ear to the next.

And so we either threw fists or didn’t, mostly over our broken hearts. To “win” meant nothing, of course. A part of this particular brand of beef meant the brokenhearted fighting or not fighting in an attempt to heal the ego, but not to bring themselves closer to being back with the person who broke their heart. A person they maybe loved but probably just liked a little bit, in a time when love was most measured by proximity and not emotion. It’s easier to circle someone in an endless waltz of volume and eye contact than it is to tell them that they’ve made you very plainly sad. And so, there is beef, the concoction of which at least promises a new type of relationship to fill the absence.

There are many ways the beef can begin with a dance move and then spiral outward. Just ask James Brown and Joe Tex, who both kicked their microphone stands and did their splits and there’s no real telling who got to it first, and it is safe to say that neither of the two invented legs or the high kicking of them. But Joe Tex definitely got to the song “Baby You’re Right” first in 1961. He recorded it for Anna Records at a time when he was searching for a hit. Tex first came to prominence in 1955, after he stormed into New York from Rogers, Texas. In his junior year of high school, he won a talent show in nearby Houston; the prize was $300 and a trip to New York, complete with a weeklong hotel stay at the Teresa, situated in close proximity to the legendary Apollo Theater.

I wish more people talked about the moments that build up to a potential brawl as intimacy.Amateur Night at the Apollo Theater was the first and truest proving grounds for young artists, because there was no real barrier between the performance and the audience’s expression of pleasure or displeasure at the performer onstage. The audience was empowered to display their distaste for a performer’s act, both vocally and even physically, with demonstrative actions like running into the aisles and shouting while pointing fingers, or—if pleased—pretending to faint with joy. The Apollo existed in the days before paneled judges would offer feedback, when even the rudest of comments from a judge seem scripted and a little too made-for-television.

At the Apollo, the audience was there to perform just as much as the person onstage. Like any good audience in a schoolyard escalation, they could dictate the arc of a night, or a whole life, right in the moment. It can be argued that no roomful of people should have this much power, but the crowd of largely Black people was there to give mostly Black performers what they needed: honesty from their kinfolk.

In a moment, I will return to foolish-ass James Brown, who stole “Baby You’re Right” from Joe Tex and so maybe it could be said that he also stole the dance moves or at least had the theft of his own dance moves coming. But now is the time to mention that when Joe Tex arrived for Amateur Night at the Apollo back in 1955, Sandman Sims was the person who had the honor of playing the role of the Executioner. The audience loved the Executioner, but performers didn’t want to see his ass while they were onstage, because if that nigga is coming out after you, that means your time is up. By the time you see the Executioner, the boos are probably so loud that the audience can’t hear whatever shoddy rendition of that thing you were doing anyway. The Executioner’s job is to cleanse the audience of whatever it was they were enduring, by running onstage and tap-dancing the performer off while the boos gave way to cheers.

Howard “Sandman” Sims once wanted to be a boxer out in California but broke his hand twice as a young man, and you can’t box if you can’t keep a fist closed, but the joke with him was that he wasn’t much of a boxer anyway. He was known for how he’d move around the ring. The age-old idea of the desire to dance outweighing the desire to actually get into the messy throwing of punches. He’d look almost like he was floating, dodging and ducking and juking. The sound his feet made as he bounced around the ring, shuffling the rosin around the wood. Like sand being kicked up everywhere.

When he figured out dance as a career alternative to boxing, he tried to glue sandpaper to his shoes or to his dancing mat, in an attempt to reproduce the sound of his shoes moving around the boxing ring. When that didn’t work, he sprinkled sand on flat platforms to create soundboards. This was in the ’30s, when movement was king, and sound and the body were becoming one. Tap dancers like Sandman carried shoes with them everywhere they went, and if they spotted someone else carrying shoes, one dancer would throw their shoes down on the ground, initiating a challenge, which would take place right there in the middle of the street.

Sometimes the beef begins with a clatter of shoes against pavement.

Sandman left California and moved to Harlem in the early 1950s. He’d swept through all of the street dancers in Los Angeles, then he heard there were ones in Harlem who could dance on dinner plates without breaking them, or tap atop newspapers without tearing them. Those challenges were more than worthwhile, but Sandman had his eyes set on Harlem for the famed Apollo Theater. He’d heard word of the Wednesday night show, where amateurs could seek glory on the stage. He would go on to win the competition a record-breaking 25 times. After the 25th time, a new rule was made: performers were no longer allowed to compete once they had earned four first-place prizes.

One of the many problems with beef—as it has been constructed throughout history—is that bystanders are used as a currency within the ecosystem of the disagreement.The Sandman had conquered the Apollo and rewritten its history but had nothing particularly tangible to show for it. He still didn’t have steady work as a dancer, or much of anything else. In the mid-50s, the Apollo decided to hire him as a stage manager. Shortly thereafter, he began his role as the Executioner. He revolutionized the role, not only dancing performers offstage but adding comedic elements to it, like chasing them off with a broom or a hook while wearing clown suits or diapers. It was all a trick to pull the audience back from the brink of their displeasure and give them something satisfying in between acts.

Story goes that once he got the performers safely backstage, he would drop the act and console the people who needed it. Sandman was the longest-running Executioner at the Apollo, staying in the role until 1999. The entire time, despite having a job that paid, he’d still carry his dancing shoes with him on the streets of Harlem, throwing them down for a fight whenever he saw fit.

But Joe Tex never met the Executioner during his time on the Apollo stage, because he never got booed off the Apollo Stage. He won Amateur Night four weeks in a row before he’d even graduated from high school. When he did graduate, in 1955, he immediately got signed to a record deal with a label called King Records, out of Cincinnati, Ohio. They were known best among Black people as Queen Records, which distributed a run of race records in the 40s before folding into King, where the focus became making rockabilly music, and Joe Tex seemed like a star in the making. He was charismatic, a sharp songwriter, with a voice that hit the right kind of pleading—like a gentle and trapped bird asking for escape.

The problem was that early on in his career, Joe Tex couldn’t channel any of that into a hit. He recorded for King between 1955 and 1957 but couldn’t break through with any songs. In an old label rumor, it was said that Tex wrote and composed the song “Fever,” which eventually became a hit for King labelmate Little Willie John. Tex sold it to King Records to pay his rent. This was, I imagine, the first sign that Tex’s time at King was in need of coming to a close.

Tex moved to Ace Records in 1958 and continued to be unable to cut a hit, but where he could always eat was on the stage. There he was a step ahead of his peers. He garnered a singular reputation for his stage acts, pulling off microphone tricks and dance moves that hadn’t been seen before. Including his main gimmick: letting the mic stand fall to the floor before grabbing it, right at the last moment, with his foot, then proceeding to kick the stand around, on beat with the song he was singing. His onstage stylings got him cash and a few choice opening gigs. He would open for acts who were also ascending, as he was, but were seen as having more star potential. Acts like Jackie Wilson, or Little Richard. Or James Brown.

This of course is not to say that James Brown waited in the wings and watched Joe Tex, studying his dance moves and mapping them out for his own use. But James Brown sure could make a mic stand do whatever he wanted it to, and so could Joe Tex, and some would say—again, there’s just no telling. Back to “Baby You’re Right”: Tex recorded that tune in March ’61, when Anna Records was owned by Anna Gordy, Berry Gordy’s sister. Tex was looking to build a pipeline to Motown, and so he recorded “Baby You’re Right” for them, and a few others. The song was unspectacular for its era, with a slow finger-picked guitar backbone and bursts of horns punctuating the lyrics, affirming to a lover that she is missed.

Here is where James Brown enters again. Later in 1961, James Brown recorded a cover of the song, altering the melody and changing the lyrics slightly. Brown’s lyrical melody drags out the words, adding a palpable urgency to the questioning. “Yooooouuuuuuuu think I wanna love you?” hangs in the air for a touch longer than Tex’s version did, while the listener—even if they know the answer—eagerly waits for a response. Tex was singing to convince his beloved, while Brown was singing with the understanding that his beloved was already convinced. It was enough to catapult James Brown to the pop charts and the R&B Top Ten. Brown chose to add his name alongside Tex’s as a songwriter in the credits.

Tex, who hadn’t been able to break onto the charts at all in his career, finally got there. A small circle of light inside the shadow of James Brown.

***

I lied when I said winning meant nothing, and this is how you can tell that I have lost enough fights to know I should stop fighting. The ego’s ache calls for bandaging, and that salve could come in the way of dominating an opponent in a physical fight, or getting to a song before they do, but the ego will call for the salve nonetheless. A dancer throwing their shoes at your feet is attempting to push your pride past the point of no return. To say they know you and what you are capable of better than you know yourself. It is good to know you are feared. It’s what kept the Sandman running into the streets, and what kept performers on the Apollo stage from clocking him one when he ran out in the middle of their performances with a broom. Winning sometimes means you can opt out of whatever violence comes for you next. Winning sometimes means you get to go home with a clean face and no questions from your worried kin.

It was the wedding scene that kept New Jack City out of some theaters in my city when the film touched down in the late winter of 1991. The whole film is about the depths the powerful will go to in order to maintain power, but the wedding scene is specifically harrowing. While walking down the steps after the ceremony, one of the young flower girls drops one of the wedding accessories. As she retreats back up the steps to get it, the kingpin, Nino Brown, bends down to retrieve it and hand it back to her, a smile mapping its way along his face. Something was always going to go bad because Nino’s in all black at a wedding, dressed like he’s prepared to bury or be buried. And anyone with half a mind could peep the scene and know that the caterers closing the doors of their van at the bottom of the steps were actually the Italian mobsters, looking to settle a score. But it’s already too late, even if you knew what was on the horizon. The mobsters have their guns out and start firing, the way guns are fired in movies—haphazardly but not really hitting anything.

If the scene were to simply spiral into your run-of-the-mill movie shootout from here, it would be unspectacular, and unworthy of controversy. But there is a moment that lasts about four seconds. As the young girl’s father runs back up the stairs to protect his daughter, as bullets kick up small kisses of smoke from the concrete, Nino snatches the screaming girl and holds her over his face and torso, using her as a shield. Even within the precedent of horror set by the film, it is an especially horrific scene, clearly situated within the film to push the boundaries of violence but also to draw a line in the sand on Nino Brown as a character who could be redeemed by any reasonable audience.

Parents in my neighborhood caught wind of the scene when reviews came out. There was pressure for theaters to drop the film from their lineup, and some did. Local news panicked about the movie inciting violence—a threat that would be bandied about later in 1991, when Boyz n the Hood dropped, and in 1993 when Menace II Society came out.

It is the part of the film that most clearly articulates that power—particularly for men—means having access to bodies that are not yours as collateral. Countless options for remaining unscathed.Those who could snuck out to see the movie anyway. I was too young to see it in theaters, but not too young to hear the older hustlers and hoopers dissect it on the basketball court across the street from my house, or listen in on my older brother talking about it with his friends. If it’s real beef, the kind with bodies left bleeding out in a city’s daylight, then the stakes become different. Someone is dead, and so someone else has to die. But even among the streets there is a code, usually revolving around women and children, funerals and weddings. Nino Brown was unsympathetic because he didn’t have a code, I’d hear. And to see the lack of a code played out in the manner Brown chose rattled the foundation of those who did tend to their beefs with a firm understanding of who bleeds and who doesn’t.

The full shootout lasts just over a minute, but the part of it that is not as memorable to most as the child-as-shield moment comes at the end. As Nino Brown and his crew hide behind tables and wedding gifts, firing their own parade of reckless bullets in the general direction of their foes, the mobsters slowly begin to retreat. Somewhat inexplicably, Keisha, the lone woman member of Brown’s gang embroiled in the shootout, runs out to the center of the steps with her gun and begins firing. Expectedly, free from the cover of the wall she was hiding behind, she is hit with a stream of bullets, each painting a small red burst along her cream-colored suit. She collapses to the steps, and Nino Brown survives. It is the part of the film that most clearly articulates that power—particularly for men—means having access to bodies that are not yours as collateral. Countless options for remaining unscathed.

For James Brown, that option was Bea Ford. Ford was a background singer with a sharp and inviting voice. She was married to Joe Tex until 1959, and in 1960, James Brown recruited Ford to sing with him on the song “You’ve Got the Power,” a slow, horn-soaked ballad that opens with Ford singing:

I’m leaving you, darling

And I won’t be back

I found something better

Somewhere down the track

By the time Brown’s voice enters the song, his and Ford’s vocals are stitched together, inextricable, as if they’d known each other an entire lifetime.

At some point after the song’s release, Brown sent a letter to Tex. The letter insisted that he was “done” with Ford and that Tex could have her back. In response, Tex recorded the song “You Keep Her,” which opens with the lines:

James I got your letter

It came to me today

You said I can have my baby back

But I don’t want her that way

So you keep her

You keep her because man, she belongs to you

There are many ways to poke at a person over a long stretch of time, digging the knife into their worst insecurities and then twisting the blade. The word “belongs” is the blade here, I suppose. If one searches wide and far on the Internet, there isn’t much about Bea Ford to be found. The only recording she’s ever credited for is the duet with Brown, and she didn’t last on the James Brown Revue much longer after the song was released. The first photo in a search is of her standing at a microphone singing while a young James Brown watches, expectantly.

One of the many problems with beef—as it has been constructed throughout history—is that bystanders are used as a currency within the ecosystem of the disagreement. When the beef is between two men, those bystanders are often women. Women who have full lives, careers, and ambitions but are reduced to weapons for the sake of two men carrying out a petty feud. This is the downside to it all. Beef is sometimes about who has and who doesn’t have, and with that in mind, even people can become property.

And so, in the midst of all the fireworks, and all the thrilling talk about fights and the public rubbing their hands together to see who will spark the next match, I don’t want it to get lost that Bea Ford was a woman of talent. A woman who perhaps had career ambitions beyond the men she found herself in between. A woman I have to largely speculate about, because the only information easily found about her is that she was once married to one singer until she was singing a duet with another. There is something damaging about what happens in the periphery of two men fighting with each other. The ego of a powerful man detonates, and in its wake is a land that looks nothing like it did before the explosion. Even the clearest memories become wind.

__________________________________

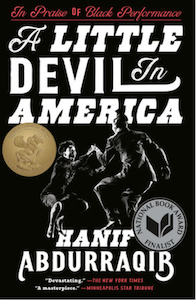

From A Little Devil in America. Used with permission of the publisher, Penguin Random House. Copyright © 2021 by Hanif Abdurraqib.