My boss and I start the day with many pencils, four of five of them, tools as necessary to us as carpenters as our hammers and our drills. The flat carpenters’ pencils with a thick tip don’t roll. Tipless old Ticonderogas poke out of tool bucket pouches, their pink eraser butts have the feel of a flexed thigh; a couple quick flicks with the utility knife, cedar curls on the floor, and the sharpened point is ready to write. Mary, my boss, who’s taught me the carpentry trade for the last six years, often tucks one behind her ear. I keep mine in my right back pocket, tip up, which results in inadvertent scribbling when I get my ass too close to a wall, or sit down on the couch after work, forgetting it’s there, and leave a pencil smudge on a pillow.

As the workday goes by, our pencils disappear, eaten by the tool bucket, swallowed by the saws, abandoned out of sight in some crack or crevice. We start the day with fresh points, safely stored and ready to mark. We end the day with questions. Do you have the ¾ where’s my ¾ I’ve got two in my pocket ¾ there’s one behind your ear ¾ where’d I put the ¾? Crucial and elusive, tool of sketchbooks and rough drafts and measure marks. The sharpness of the tip can impact the precision of your cut. Water won’t erase a pencil mark, but the smudge of a thumb will.

The pencil’s predecessors were called penicillum in Latin, the diminutive of peniculus, meaning brush. Peniculus itself is a diminutive of penis, which means tails. Henry Petroski, in his book The Pencil: A History of Design and Circumstance, chastens us: “Our interests are better served by looking at the functional rather than the Freudian antecedents of the object.” And he delineates the difference between pencil and pen: “Ink is the cosmetic that ideas will wear when they go out in public. Graphite is their dirty truth.”

In our work, we use pencils for measure marks, sketches, scribbles, materials lists, quick math on scrapwood or drywall. These are the dirty truths of building, dirty and first.

Back at the beginning of my work as a carpenter, when I was first learning the trade, Mary and I were building a deck, a small deck with a set of stairs out the backdoor of a house on a dead-end street in Somerville, Massachusetts. It was the first one for me, and the process of building it was blowing my mind. I’d come into the job with zero experience, barely knew how to drive a nail, and this was a powerful thing to see, that this deck, a structure we could stand on, came to exist as the result of our efforts ¾ Mary’s math and design, my chopping of boards.

When we’d fastened the final post cap, I stood back and beamed, excited and proud.

“Do you ever sign your name?” I asked Mary.

She pulled shreds of tobacco out from the end of the cigarette she was rolling and patted her pockets for her lighter. “Do I sign stuff?” she repeated, lighting the smoke.

“Yeah, like carve your initials somewhere or something?”

She exhaled a lungful of smoke. “No,” she said, in a way that said of course not.

I’d come from the world of journalism, from the world of bylines. I was used to having my name attached to work I’d done. And here I was with a splinter in my palm and a speed square in my hand feeling impressed as hell and proud of this new deck, and it seemed right that we should make note that we were the reason this thing existed, that we were the people behind the work. I also wanted to signal to workers down the line. In dismantling the rotting deck that we’d replaced, I had hoped to find some initials carved, a date, some hello to us from the carpenters who built this thing before. No such luck.

I realized the urge to note my name was longstanding. In all my bedrooms, as a child and adult, before moving out, I’ve climbed on stools and chairs and once a ladder, and written my name in pencil in tiny letters in a corner of the ceiling. Age eleven, and about to move across town, I wanted to signal to whoever might next occupy the room, some boy or girl, that the room had been mine, a small sign that I was here, too to whoever would spend their nights sleeping in that room after me, breathing new life into the house, breathing in the old life there as well. Did you find it? Did your parents paint over it? You couldn’t tell from the floor what it was ¾ a smudge of dirt, a spider web, a shadow. I think back on the rooms and wonder if anyone found my name, and if they felt, like I wanted them to, the way I would have if someone had left their name for me: haunted, as though I existed there still, a ghost.

Back at the deck we’d just finished, I pulled the fat orange pencil from my back pocket.

“You want to sign your name?” Mary said with a mix of amusement and skepticism. “Go ahead and be my guest.”

I ducked into the underside of the deck, stood in the corner. It was dim under there and cooler out of the late afternoon sun. Pencil poised to write, I turned to look at Mary. She made a gesture with her chin that said, go ahead, get on with it. I raised the pencil to a place on a board in the corner where the deck met the side of the house. It would be hidden, unless you were right up under the spot. In small neat letters, with a vandal’s thrill, I wrote Mary and Nina and the August date. I turned and gave Mary a thumbs up. She shook her head.

To sign names is to prove existence, to take ownership of the work. In marking initials, in carving our names, in putting tiny letters in pencil in the corner of a ceiling, we say I was really here, and this real thing is here too because of the work we did. On that first deck, unused to this new life, I was trying to make it feel real for myself, too. I am here in the work, is what the signing said.

I’d like to be able to say the impulse faded with time, but it hasn’t. I still feel tempted to sign my name or leave secret messages behind walls, on studs and joists, on the backs of cabinets, in secret places only found when the wall is opened up again. And it’s because I always wish to find secret notes left for us when we open up walls. I want to find a time capsule tag ¾ Hello from 1822, Jed + Ethan. Hello old hands who also touched this wood, who helped build the skeleton of this house. I feel your presence and nod to your work.

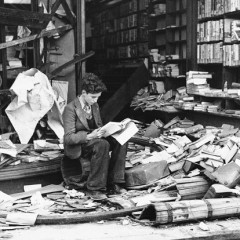

We haven’t found many notes left for us. We have found marbles, old newspapers, a girl’s white ice skate, odd things to excavate from inside the walls of a house. A ghost girl appears, one foot skateless, half gliding, half padding sock-footed across an icy pond. She’s part of the energy of the house, long-gone but there still.

William Faulkner, whose sentences are logs, credited the builders of houses, not the inhabitants, with breathing life and spirit into the walls. He writes in Absalom, Absalom!: “…as though houses actually possess a sentience, a personality and a character not from the people who breathe or have breathed in them so much as rather inherent in the wood and brick or begotten upon the wood and brick by the men who conceived and built them.” But surely it’s a combination that gives a house its character ¾ the wood and brick and metal, the conceivers and the builders, and the inhabitants, the people who rest their bones, share meals, argue, betray, abuse, take shelter and solace in the home. These all, in combination, give life to the house. And in writing our names in the walls in pencil, we sign that spirit, as contributor to it, co-creator of it. We’ll be ghosts for someone someday, I hope, our names there in the skeleton or the corner of the ceiling.

From HAMMER HEAD. Used with the permission of the publisher, W. W. Norton & Company Inc. Copyright © 2015 by Nina McLaughlin.