Hal Ebbott on Writing a Novel of Male Friendship

Jane Ciabattari Talks to the Author of “Among Friends”

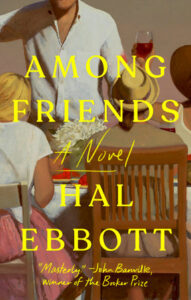

Hal Ebbott’s extraordinary first novel, Among Friends, opens with a brief prelude in which the two friends, Amos and Emerson, meet in college. It’s August, only athletes have returned. “In the distance, boys sweep across sharp, nearly cut grass. The ball predicts their turns; sweat spreads like moss on their shirts. Eventually they will stop and come up the hill, their smiles brilliant, exhausted. One pushes another. The group receives him, this act of love.” Amos studies Emerson, the boy pushed, whose “brown eyes accept the campus like something owned.” He notices how he moves “with the lazy grace of a prodigy, natural and untended. Amos was better, and at the time he had been glad. But walking beside him now, he feels ashamed of his effort. The summer hours spent sweating grow needful and unsightly.” It turns out they are roommates. And soon to be best friends.

This opening brought me back to James Salter’s Light Years (there’s a new Vintage edition just out, honoring the fiftieth year of its publication and Salter’s hundredth birthday June 10), another novel about friendship, marriage and family, with an opening paragraph I return to regularly: “We dash the black river, its flats smooth as stone. Not a ship, not a dinghy, not one cry of white. The water lies broken, cracked from the wind. This great estuary is wide, endless. The river is brackish, blue with the cold. It passes beneath us blurring. The sea birds hang above it, they wheel, disappear. We flash the wide river, like a dream of the past. The deeps fall behind, the bottom is paling the surface, we rush by the shallows, boats beached for winter, desolate piers. And on wings like the gulls, soar up, turn, look back.” Gorgeous lines that show Salter’s genius with sentences, perspective, observation, detail, fresh language, all the novelist’s skills. And profound lines like this: “There are really two kinds of life. There is…the one people believe you are living, and there is the other. It is this other which causes the trouble, this other we long to see.”

Among Friends has echoes of Salter’s brilliance, in its elegant lines, flawless metaphors, and its mirroring of the cracks and shattering implosions lingering just beneath the surface of our closest connections.

Photo © Beowulf Sheehan

*

Jane Ciabattari: You open with the moment when two college roommates meet for the first time, with Emerson, one roommate, perceived as more entitled, more naturally confident, by the other, Amos, who comes from a lesser economic background. What drew you to write a novel about this type of male friendship?

It was far more interesting to interrogate a dynamic between men who have no problem expressing their love….Love and toxicity are hardly unfamiliar bedfellows.

Hal Ebbott: American culture tends to privilege romantic and familial relations as the bedrock of a good life, with friendship falling in the category of “nice to have.” As someone who believes it ought to garner the same degree of respect and concern, I was drawn to the way this story could do that. Marriage is certainly crucial to these characters’ lives, but it tends to orbit the friendship rather than the other way around.

As for the idea of specifically male friendship, much has been made about the epidemic of loneliness, and we’ve all encountered the bog-standard stuff regarding men’s fecklessness when it comes to emoting and so on. Hopefully the dynamics here ring a bit truer. I have many wonderful male friendships full of affection and vulnerability, as do lots of men I know.

Plus, it was far more interesting to interrogate a dynamic between men who have no problem expressing their love and yet, despite that, still find themselves in the position they do. Love and toxicity are hardly unfamiliar bedfellows.

JC: Some thirty years later, Amos, his wife Claire and daughter Anna, are driving north along the Hudson from New York City on an early October day to join Emerson, his wife Retsy and daughter Sophie, to celebrate Emerson’s fifty-second birthday. The two men have been best friends for decades, not without some simmering dark undercurrents. How did you develop the narrative arc of this friendship as it approaches a breaking point?

HE: The “breaking point” was really the germ of the novel, so in many ways writing felt more like excavation than creation, a retroactive attempt to understand how such a thing could occur. You know certain details—or think you do—and from there you can feel your way a bit further. But at every point you’re ringing a kind of tuning fork, asking, “Is that true? Is that true? Is that true?” Ideally, this leads to a place where even the unthinkable doesn’t seem senseless.

JC: What made you settle on this title? Was it your working title?

HE: I liked a couple things in particular about this title. First, that it can be read in two tones: either the comforting or the slightly more sinister. Dualities of that kind often appeal to me, but felt especially apropos here. In addition, the phrase itself, the words, seemed to sit nicely in my hand. I could roll them around like marbles. They had a pleasant weight.

JC: How complicated was it to develop the intimate third person interior point of view sections for each character—Amos and Emerson, their wives, Claire and Retsy, their daughters, Anna and Sophie. Did you always intend this to be a polyphonic narrative?

HE: Certainly it could feel difficult to hold things in my head, let alone get to a place where each character seemed warm-blooded and alive. But it never felt tenable to be constrained to a single point of view. I suspect that’s something of a personal disposition as well as a demand of the story. Even now, the thought makes me feel panicky and claustrophobic in a straitjacketed way.

JC: How are you able to be so detailed and specific in describing the frustrations and pleasures of these two long-term marriages? And the mother-daughter, father-daughter relationships, as the girls are now sixteen?

HE: I’m flattered by this question, of course, though I’m afraid I won’t have an especially concrete answer. I’ve never been married and I don’t have any children. But I do love people. They’re pretty much all I care about, and I try as hard as I can to pay attention. Beyond that, I suppose it might come down to a hopeful kind of faith—that somewhere within my experience of being alive are the materials to help me understand this other thing.

JC: Emerson’s birthday weekend includes a shocking event that could end this friendship, even undermine all the complex family relationships you have created. The second half of the book unspools the possibilities for these six characters to move forward. You explore the alternatives in intriguing ways. Without spoilers, can you say if you had your ending in mind all along? Or other alternatives?

I suppose it might come down to a hopeful kind of faith—that somewhere within my experience of being alive are the materials to help me understand this other thing.

HE: I never had a particular ending in mind. As with the leadup, this was really a question for the tuning fork. I did try the final section in multiple ways, and there were certainly endings which, on a personal level, I would have preferred. But none of them ever rang true. I never really believed in any outcome but this.

JC: Who is most alone at the end of this novel, Amos? Emerson? Anna? And why?

HE: I’m sorry to be so unsatisfying, but I don’t think that’s for me to say. I’m much more interested in a reader’s impression of this!

JC: Among Friends reminds me of James Salter’s novel Light Years. I’m curious about the writers whose work you admire. Which writers might have influenced you?

HE: Once again, this flatters me immensely. I can think of few writers who come closer to James Baldwin’s imperative that sentences be “clean as a bone.” Elsewhere, I often find novels with tight frames to be compelling. Christopher Isherwood’s A Single Man and Paula Fox’s Desperate Characters come to mind (Virginia Woolf too, of course, plus Claire Keegan and Barbara Pym). There’s a satisfying constriction in these which feels immersive to me as a reader, and as a writer affords the space to fixate on minutia that might not be appropriate in something more expansive. Though a completely different medium, Jacqueline Novak’s “Get On Your Knees” is also a wonderful example of what can be achieved by confining oneself to an ostensibly small box.

I do read a fair amount of poetry as well, and look to it for a kind of sentence-level courage. Some favorites include Louise Glück, George Oppen, Anne Sexton, and Sharon Olds.

JC: What are you working on now/next?

HE: It’s probably premature to be much more specific, but in general my interest tends towards situations which strike me as fertile in a dense, compressed kind of way. If something feels excruciating to think about, that’s probably a good sign.

__________________________________

Among Friends by Hal Ebbott is available from Riverhead Books, an imprint of Penguin Publishing Group, a division of Penguin Random House, LLC.

Jane Ciabattari

Jane Ciabattari, author of the short story collection Stealing the Fire, is a former National Book Critics Circle president (and current NBCC vice president/events), and a member of the Writers Grotto. Her reviews, interviews and cultural criticism have appeared in NPR, BBC Culture, the New York Times Book Review, the Guardian, Bookforum, Paris Review, the Washington Post, Boston Globe, and the Los Angeles Times, among other publications.