Grown Ups Were Getting on Her Nerves, so Rivka Galchen Wrote a Kids’ Book

When Writing for Adults Loses Its Joy

In the middle of the second presidential debate of 2016, my computer made a high-pitched whistling noise. The (horrible) image on the screen contracted into a single dot of light. Then even that went out. Okay, I thought, that was strange, but surely it’ll be okay. I tried turning my laptop back on with this arrangement of keys. Then with that arrangement of keys. I tried turning it on connected to power, I tried turning it on not connected to power. I began to panic. Sometimes, a pale gray bar would briefly, tantalizingly, appear on the screen. Eventually not even that. The next day I went to the computer store. Then I went to the messy back desk of the even more tech-savvy computer store. Then I shipped the laptop off to somewhere in Northern California. They told me they’d let me know more in about three weeks.

I had no backup for the files on my computer. This is because I am very bad with technology. Or did I have no backup because I was as annoyed with my files as I was with everything and everyone else that year? The magicians in Northern California told me that they could usually save 85 percent or so of the things that were sent to them. Then the magicians in Northern California told me that the files were gone.

*

That spring and summer of 2016, most everyone I cared about was staring intently at the glow of a screen for hours and hours and hours, often late into the night. The screen-glow began to feel like the menace, rather than the very menacing news being read on the screen. It was a switcheroo, but a convincing one. I had a vivid dream/nightmare in which I came out of the bedroom to find everyone I loved staring at an enormous glowing white lantern. Then stepping into the lantern. Then disappearing into it. Then I had that dream again.

I had long wanted to write a novel for children in part because I was reading novels for children—to my daughter, but also to my younger self—most days. That reading was the best part of the day: the part of the day when I was amusing my very favorite person. You may also remember about 2016 that pretty much everyone got on your nerves. At least that was what it was like for me. Even my friends, most of whom held pretty much the same values as me, filled me with rage with the tiniest observation about politics. One good friend wrote an excellent piece about an intelligent woman who, it was clear, she really didn’t like—and even that seemed to me as much a harbinger of an awful November as the Brexit vote.

What I’m saying is: I also wanted to write for children because they were the one demographic left that I straightforwardly loved.

In addition to reading lots of children’s literature, when I was traveling with my daughter on a subway and forgot to bring a book, I told her stories that I made up. They were very rough first drafts—even kind of boring! —but she never seemed to mind. On the contrary, a “made-up” story was always her first choice. What mattered most to her in these made-up stories was sticking to a cast of recurring characters; she wanted serial adventures. I began to understand why the short serial form—basically the Victorian novel—translates so well into kids’ books. Not that I ended up writing quite that kind of book. Maybe next time.

*

But what kids’ novel did I dream of writing? One that my daughter would like, and one that I would have liked as a kid.

As a kid I was pretty happy. Which is not what people expect to hear when they learn I grew up the daughter of Israeli immigrants in Norman, Oklahoma. I didn’t have many books, but I still had lots of words to read that I loved. Those words included: the wrapper jokes of Bazooka bubble gum and also of Laffy-Taffies; the nutritional information on the sides of cereal boxes, and also the games there; the kids’ science magazine 3-2-1 Contact!; all the science books from my dad that mostly went over my head but that I still loved—there was one about Penrose Tiles, there was also A Brief History of Time by Stephen Hawking, and everything by or about Richard Feynman; then there were those Magic Ink Puzzles we bought at truck stops when we went on road trips—those were maybe my very favorite of all. There was a book of brain teasers written by someone who I was told had also written a book about running but had died of a heart attack at a young age. And I adored the puns and play with catchphrases in The Phantom Tollbooth by Norton Juster. My dream for the children’s novel I was writing was that it would manifest at least glimmers of all those things I had loved as a kid.

And that it would start with that lantern, which I found so spooky and compelling.

It was fun to stumble across my own feelings in a funhouse mirror.The only reason I wasn’t writing the kids’ novel was that (in my mind) I had to, had to, had to finish the grown-up novel—the one that had vanished in the hard drive crash in the middle of the presidential debate.

My “adult” novel was—it’s always embarrassing to say or even think these things—about a male pregnancy. I thought of it as a kind of Frankenstein story, which is to say also a sweet story, about learning to love certain kinds of monstrosity, the difficulties therein, etc. Then, suddenly, that person who was interested in loving monstrosity, in the power of pregnancy manifesting in man—that person who was me had been crushed, or maybe had simply vanished. If I had finished that book, after that computer crash and in those seasons that followed, I would have been just connecting the dots, or mad-libbing my way through the rest of the project—but mad-libbing in a bad way. I can imagine mad-libbing in a good way. But it wasn’t working. I also had a short story that was 90 percent done when I lost everything. I decided to try and rewrite that story from memory—I felt like I remembered it all, even its little turns of phrase. But the remembered story read like speaking with a hot stone in your mouth. None of the words sounded right. And it was painful.

When I would try to work on any of my “grown-up” work, I felt heavy and even like I was faking it. Faking what? Maybe faking that I was having fun. For me, writing is a kind of playing. It’s supposed to involve some joy—that’s the only time it’s even half-good.

When I worked on the kids’ novel that I told myself I wasn’t really working on, I had joy in my heart. Sappy but true. That was how the last book I had finished and been pleased with had happened, too—with some love and joy, and not according to plan. It was like being a kid again, but without the difficulties of reaching the popsicles at the back of the freezer, and without the maddening lack of autonomy.

Each incidental character satisfied something frustrated or fearful within. I found my characters needing to cross a Sea of Technically True Things—just as I so often do. In that sea were Insult Fish who rudely shouted things that were, well, technically true: they call the main character One-Nosed, and Bipedal, and Lonely. When the characters meet the Rat Queen—a mother, like me—she’s eating trash, and is a grouch, having passed a catastrophic rule of No One Being Allowed to Get Older in the first place. I got a kick out of her because of course I also found it objectionable that my daughter wouldn’t always be little. It was fun to stumble across my own feelings in a funhouse mirror. Especially since it always felt like another random invention—just another little story made up to pass the subway ride from 34th Street Penn Station down to Chambers Street.

My main character does finally make it out of the lantern, but part of what she and I learned along the way was that maybe the lantern was not the only broken place around—or the only magical one. I discovered that the Rat Queen’s growth had to be finding a way to like not only children, but even older children, maybe even adults, again. At least a little bit.

__________________________________

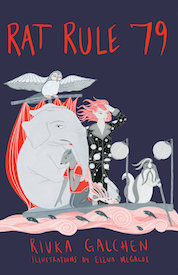

Rivka Galchen’s Rat Rule 79 will soon be available from Restless Books (Sep. 24). Copyright © 2019 by Rivka Galchen. Illustration copyright © by Elena Megalos. Featured with permission of publisher, Restless Books.