Growing Up with Classic Russian Literature in Rural South India

Deepa Bhasthi on Her Grandfather's Collection of Cheap Soviet-Era Editions

“It is to books that I owe everything that is good in me. Even in my youth I realized that art is more generous than people are . . . I am unable to speak of books otherwise than with the deepest emotion and a joyous enthusiasm . . .—I am beyond cure.”

–Maxim Gorky in a preface to a book by P. Mortier, Paris, 1925

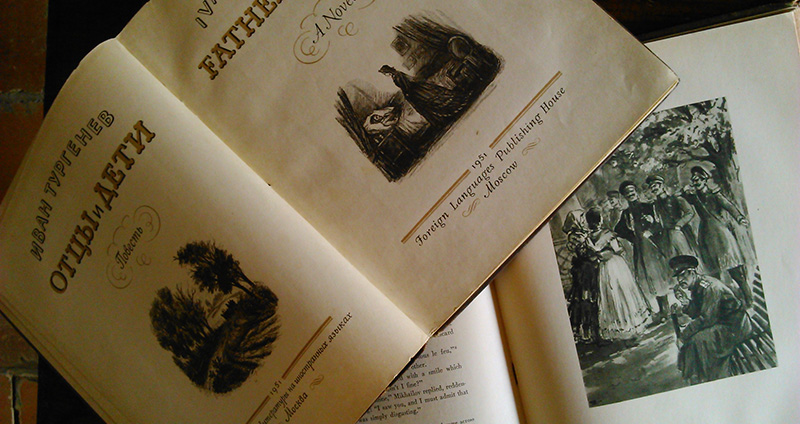

My edition of Gorky’s On Literature, which includes the essay On Books quoted above, has a beautiful, asparagus green cover. The “On“ is printed in neat calligraphy, and the pages are a soothing cream color. It was translated from the Russian by one V. Dober, printed in the USSR, and published by Foreign Languages Publishing House (FLPH), Moscow. The book smells, like all old books, of warmth and magic.

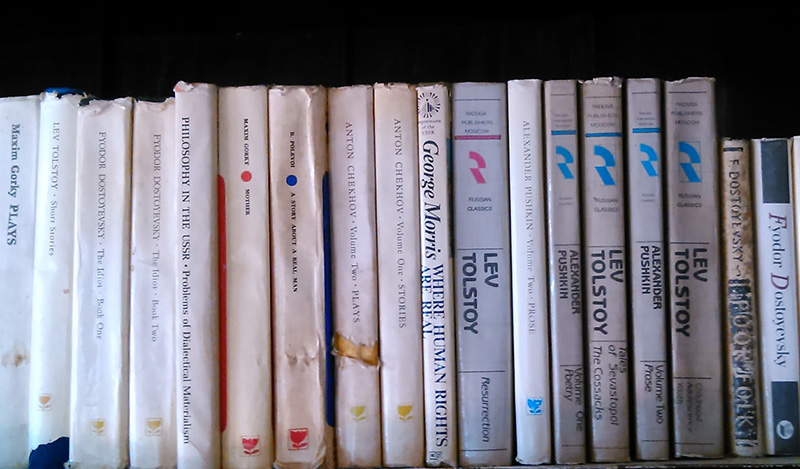

The magic, to the initiated, lies a lot in the name of the publishing house. FLPH—along with Raduga Publishers, Progress Publishers, Mir Publishers and some lesser known others—was an essential part of the growing-up years of a few generations of Indians in the mid-20th century. Starting in the 1950s, until the tail end of the 1980s, the USSR spent a lot of money and manpower flooding India with Russian literature classics, children’s books, science and technology textbooks, philosophy, handbooks on political and social theory, and other reading material meant to demonstrate the grit and glory of the Motherland. In the thick of the Cold War years, India and the USSR maintained very cordial relations, with a dedicated focus on cultural exchange, a strategy longer lasting and perhaps more penetrative than political rhetoric. While the Tolstoys and Pushkins bombarded India, Hindi movies became extremely popular in the Soviet states. Curiously, Indian literature—and Russian movies—did not cross over in the same way.

Moscow set up several publishing houses whose sole purpose was to produce books for the Indian market. These books were translated into English and most other major Indian languages in Moscow and then distributed in India at incredibly low prices. Each book cost a few cents, half a dollar or so at their most expensive. Nearly all were gorgeously illustrated, often with grand calligraphic flourishes. In a socialist era, the low cost of the books was a great incentive, and generations of Indian readers grew up as familiar with Olgas, Borises, and Sashas as they would be with Rama and Arjuna and the rest of the in-house mythological pantheon of our traditionally told tales.

What continues to intrigue me is the reach of these distribution networks, down to the smallest of towns. I grew up in a village in the hills, a blip on the map of South India. To this day we do not have a bookstore in town, except for the newspaper vendor who stocks select pulp fiction titles alongside gossip tabloids and the day’s newspapers. And when I was growing up, there were no online marketplaces to log on to, of course. But there was Grandpa and his books from Russia.

My grandfather was a famous doctor in those parts and is still remembered 35 years after his death. He also participated in the Indian Independence movement, went to prison, and came out a Communist leader who ran for election and grandly lost. He lent money he knew would never be returned, treated more people for free than he ought to have (what with a dozen mouths to feed at home), allowed his clinic to be a gathering place for idealists, and invited hippies home whenever they passed through town. And he read, my grandpa; he read everything.

He died six months before I was born. Sometimes, Grandma would look at me and quietly remark that I had inherited his forehead. Everyone else wordlessly noted that my own years of rebellion, of being liberal and Left in a family that remains traditionally Right, came from him. No one said so openly, lest I see that as a fillip. But despite never meeting my grandfather, I would come to know him well, for I grew up knowing his books well. When he died, he left behind a vast collection that—because I was born in the house he lived in, because the rest of the family didn’t seem much interested in such heretic literature—I inherited entirely.

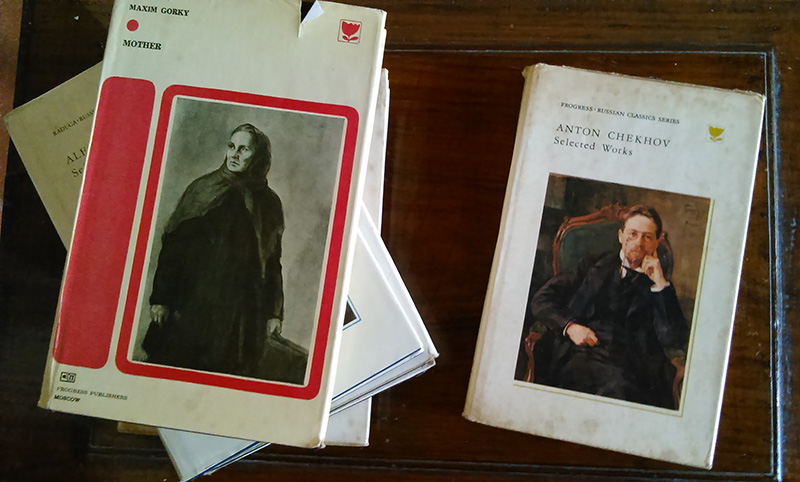

The bulk of his library was made up of books published by Raduga and other Russian publishing houses of its ilk. It was thus that by age ten or so, the first grownup book I read was Maxim Gorky’s Mother. Without a bookstore in town, without siblings on the homestead, the kinds of books I was supposed to have been reading I had long read, read, and re-read by then. I must have picked up Mother on a desperate summer afternoon. I remember the cover distinctly: A babushka with a scarf on her head, holding a box suitcase in one hand, poised to walk off the edge. Her face has worry lines; the times in which she lived were surely hard. I would thereafter pick up many Tolstoys, Pushkins, and Dostoyevskys, though it would take me over a decade more to truly appreciate the language and the nuances of these old favorites.

Now and again over the years, I have tried searching online for more information about these Soviet-era publishing houses. Though there are several websites and blogs managed by fans of these books, there is little official history. Mostly, the sites offer readers a place to list the titles they have, post photos of covers and inner illustrations, and exchange nostalgic notes about how much they loved growing up with these books.

Depending on which version of the story you want to believe, the FLHP was founded to centralize all literature meant for non-USSR readers. Sometime in the 1960s, or perhaps in 1931—no one seems to be able to decide on an exact time period—FLHP became Progress Publishers. Their logo was a combination of the Sputnik satellite and the Russian alphabet’s “P.” A couple of decades later, Raduga was formed to take over the publication of all classic literature titles, some contemporary writers, and some children’s books. Mir, working alongside Raduga, managed the science and technology titles. (A hardback pocket book on astronomy called Space Adventures in your Home by F. Rabiza fueled astronomer ambitions early in my childhood, until a physics class in high school made it clear this was an unrealistic life choice). Novosti Press Agency Publishing House for pamphlets and booklets, and Aurora Publishers in Leningrad for art books, rounded out the international Soviet publishing scene.

In a city I very briefly lived in during the early 1990s, my dad had found used copies of something called Misha, published by Pravda Printing Plant. A children’s monthly, it was bilingual, with some sections in English, crosswords with which to learn the Russian language, and cartoons, contests, even a pen-pal section.

These sparse details are all I have. There is nothing on the big wide internet about who the translators of these many books were. On an inside page, when they include a name at all, the books display only the second name of the translator—Babkov, Smirnov, Maron, etc.—preceded by an initial. I imagine translator bios were irrelevant in the greater service of the Motherland. Perhaps most well-known among the few who lent their full names to their works was Ivy Litvinova, the British wife of a Soviet diplomat working at the turn of the 20th century.

I managed to hear once about the son of one such translator, who went from Eastern India to Moscow and was employed to translate the books into Bangla, the language of his state. Translators from several Indian states were housed in apartment blocks with their families; children were born and raised there, and after the split of the USSR, some left, though many stayed back and continue to see out their lives there. I sought this person out, asked him to tell me more, but for reasons I could understand, he stopped answering my messages.

Perhaps like the folk tale of the fox and the sour grapes, it is best to leave the mystery intact instead of lifting the veil and being disappointed in its possible banality.

I hear these books are now fast becoming collectibles. For a generation that came of age at the cusp of that very strange period in India when socialism ended and capitalism was becoming wholeheartedly embraced, these books remain a kind of sentimental paraphernalia. The world depicted in the Russian stories was an exotic one, far removed from the neighborhoods of South India, different in weather, names, food, and façades. But the affordable books made it a world its readers felt able to touch, to sense and know well.

For me, the books also provided access to a second world: the one in which my grandfather lived, read, fought, and loved. I like to think at least some of the choices I make come from what grandpa would have taught me; I am in part the vestiges of who he was. His books are my assurance, my reiteration, my connection to a man I never met but have come, through the library, to know.