Growing Up in the Soviet Union’s Hero City

Or: Self-Portrait with Madonna by the Palace of the Republic

I grew up in a microregion of apartment blocks on the south-western edge of the capital city in a provincial Soviet republic that gained its independence around the time when a few girls in my class claimed they got their first periods though it would take me a few more years to get there. A long sentence, yes, but so was my apartment building, stretching for two bus stops, twelve entrances long and eleven floors high. Ours was the second entrance and I wasn’t allowed to walk past the third. The blocks were arranged in a paisley pattern; three schools stood lined up in the kitchen window like three military divisions. The apartment building and the schools were separated by playground spaces that, from the height of our sixth floor and in memory, appear to look like a metal digestive tract between the reproductive system of the apartments and the three-sphered brain of the schools.

The school hallways were brightly lit while the bulbs inside the apartment entrance were always out and the staircases stood in the dark like still water. The elevator smelled of urine; the school corridors smelled of chlorine. The cleaner the school in the morning, the sicker my stomach would turn.

Is there anything more beautiful than night in a Soviet microregion? Thousands of windows light up transforming concrete panel blocks into the hanging laundry of light, mothers lean over the stoves, the night sky reflects the glow of electricity. I would like to walk through it as through a carpet market moving the hanging carpets of apartment buildings with my hand. The air smells with mothers: their perfume, their hair spray. In their purses: lipstick, a loaf of bread, and a used public bus ticket. There is always a girl swinging on a creaking swing and cutting the air with her feet like a butcher’s knife. Who is she? Isn’t she mad from that creaking? Does her swinging wind the clocks in every apartment?

Our bedroom window faced away from the apartments and into a state dental clinic. Across the street from the clinic, there was a round cemetery, the size of a small garden. Once, the cemetery plugged a village; now the patch of old trees looked disproportionately small next to the densely-populated apartment buildings. The clinic took no appointments—first come, first serve. In winter, I’d wake up for school at 6 am and people would already be lined up. From the top of a bunkbed on the sixth floor, I’d sense human movement in the outside dark, in a DNA-like ribbon each human link was—a swollen mouth of pain.

I was always aware that I lived not on a street, but on an avenue. Living on an avenue added pathos to my microregion citizenhood. Not to mention that in school we never said “Minsk.” No, it was always “the hero-city of Minsk,” and the avenue was named after the Soviet newspaper “Pravda,” which, in English, means truth. I lived on the avenue of Truth in the hero-city of Minsk and this is my poetic prosody: start by holding breath in fear of the dark, open like a small bight elevator, hold your breath again because of the urine smell, quickly move upward, enter a warm apartment and walk room to room looking at patterned wallpaper, curtains, and crystal glassware in the cupboards that multiply square footage inside the small living space. There’s my grandmother telling stories about the war. What other stories can there be in a hero-city?

Minsk has four distinct seasons; each is its own country. Winter is like being inside the static of an untuned TV channel. Inside the winter’s static: school’s marble hallways stretch like a long electric buzz. Winter’s ice debris is magnetized by the Palace of the Republic, a gray planet that commands the rings of snowstorms. There are people bent over in the ice debris, there’s blood on the snow. There are police truncheons raised like black wheat – a city square of truncheons rising and falling like black wheat in the storm. When I look out of a school window, it’s always a winter night, and there’s always blood in the snow.

In the winter dark, the art teacher is projecting slides with Rembrandt onto a blackboard. She wants us to understand something about Rembrandt’s darkness but I look outside and it’s dark and there’s blood in the snow. She shows us Leonardo’s “Madonna Litta,” points to the ripped stitches of the Madonna’s dress. “The mother decided to stop breastfeeding and had stitched up the nursing slits in her dress,” the teacher explains, “but the divine child must have cried, asking for breastmilk, and she ripped the threads.”

The art teacher wants us to be moved. But my grandmother made her living sowing dresses simple as two plus two and most of my clothes are handmade. The magnetic pull of the Palace of the Republic is growing stronger and makes my head ache. The Madonna’s face is white without a single stroke visible on it. It seems to be washed in chlorine and, mixing with the bitter feeling about my grandmother’s sowing, my stomach turns. Outside, it’s winter static, there are people bent there and there’s blood in the snow. School’s lit up corridors are washed with chlorine. What is without a stroke? The smooth marble of monuments, the smooth marble of school corridors, the smooth marble of gravestones.

Corridor—currere—a place for running. Running in the hallways is forbidden

On each shoulder, I have epaulets of snow. There was often blood in the snow by the dental clinic next to our block, but there’s more blood in the snow by the Palace of the Republic. Blood debris circle around the Palace of the Republic, magnetized.

I close my eyes and open them back again. When my eyes open they make a sound like a creaking swing. It’s the swing that winds up all the watches in microregions. It’s the watches that mothers look into like into mirrors. They adjust their hair: each hair on their heads is a clock hand held up by a hair spray.

I lived on the avenue of Truth in the hero-city of Minsk and this is my poetic prosody: start by holding breath in fear of the dark, open like a small bight elevator.Mothers live inside concrete carpets of light. I walk brushing them gently away from my face. Only suddenly, it’s pages of a book that I’m brushing. I run through corridors—currere, currere!—I croak over the black wheat. I swim up the still water of staircases holding my breath. Inside history books, mothers are feeding the dead with our unsatisfying homework. I too am a mother and I wipe blood from the snow with a public bus ticket. After being carried in a purse next to a warm loaf of bread, the ticket is soft. Here’s my grandmother stitching punched bus tickets back up. Here are the columns of the Palace of the Republic punching holes in the people’s heads. Ice debris circle the Palace of the Republic. There is a secret corridor that leads from an ice crystal on the square to the crystal bowl in our cupboard. But the entrance into the ice crystal is blocked with a drop of blood.

Some winters are like being inside the static of a TV channel that has stopped showing the news. I look out of the window to see what’s going on at the Palace of the Republic, but I have to look through the darkness of Rembrandt first. I see a large square planted with the black wheat of police truncheons thrashing in the snowstorm. I’m safe behind the marble tape of school corridors, and “corridor” means either “run” or “there’s nowhere to run” or “time is running out.” I fail my history class which is a class on the origins of the word “corridor.” (Is it a corridor or a corridor of shame? Is it perhaps not a corridor but a long apartment block? Is it the Stalin Line? The Pale of Settlement? The Exclusion Zone?)

Operation “Winter Magic” was aimed at creating a depopulation zone on the Belarusian-Latvian border. Several hundred villages were burned with all the civil population gathered inside barns. This is why we do not build barns any more. We build the Palace of the Republic. The Palace of the Republic won’t let us be burned inside it. But first, there’s blood in the snow. But first, we have to do something with all of this blackened wheat caught in the ice storm.

This is the winter magic that is not “Winter Magic.” I live in an overpopulated microregion in a previously depopulated country and my city is a hero-city and there is blood in the snow. I’m safe behind the marble tape of school corridors. A type of torture practiced by the employees of the Palace of the Republic is called a corridor. The employees of the Palace of the Republic line up in two rows facing each other, thus forming a corridor (currere, currere!). They force the detainees to run through this corridor while they beat the detainees with truncheons: currere, currere!

This is not the old “Winter Magic” but it’s always winter. The art teacher is speechless in front of Rembrandt. Currere, currere! I close my eyes with a creak. I try to clap my eyelids like a creaking garlic mincer. Let my mother hear the creaking. Let her look out for me from the hanging carpet of light on Pravda avenue.

*

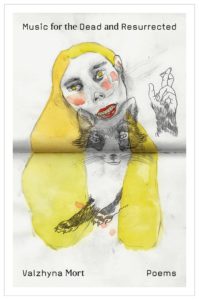

Read “Self-Portrait with Madonna on Pravda Avenue” from Valzhyna Mort’s new collection.

__________________________________

Music for the Dead and Resurrected: Poems by Valzhyna Mort is available via Farrar, Straus and Giroux.