Growing Up in the Shadow of Birmingham’s Racist Violence

John Archibald on Living with the Domestic Terror of 1960s “Bombingham”

I spoke to God last night. With him I shared my dreams. A living sacrifice, I want to be wholly accepted, Lord, to thee. But instead, to my weary soul it seems weakness and failure follow me.

–Rev. Robert L. Archibald Jr., journal entry, March 25, 1963

*Article continues after advertisement

Most people think Birmingham got its nickname, “Bombingham,” after four little girls were killed in an explosion on a September Sunday morning at Sixteenth Street Baptist Church. But that’s not true. As many as forty bombs, some lit with fuses and others detonated with timers rigged from fishing bobbers in leaky buckets, exploded across the city between the end of World War II and the Sixteenth Street blast in 1963.

Birmingham was exploding as I was born.

I know this not from Alabama schoolteachers, for they taught me none of it. At least not officially. Nor did I learn it at home. My family left the Birmingham area a few months after I was born. My father was a Methodist preacher, and we moved to larger and more prestigious churches across north Alabama, and would not return for a decade. But for years to come, the mere mention of the “Birmingham problem” drew little more than faraway looks of sadness from my mother and father.

It was turmoil and meanness from a past no one wanted to see, and it might as well have been the Civil War. It was as if all the violence and injustice in centuries of slavery and racism could be tied up in a bow and dismissed as “Birmingham.”

All that was too hard to comprehend. So it was common for reputable and important people to simply shake their heads grimly, to talk instead of just how far we’d come.

Look how far we’ve come. Just look where we’re going! Yeah, right.

So I grew up, the son of reputable and important people of goodwill, with no real idea that the state of Alabama was at war with itself, that its most prominent city was ruled by terror for decades. Birmingham and Atlanta were roughly the same size in the 1950s. Atlanta was moving forward, though, while Birmingham looked back. Atlanta called itself the city “too busy to hate.” Birmingham, as the world would learn, was not that busy.

But I didn’t know that growing up. I didn’t know how housing laws in the 1940s separated Black people from white, how failure to abide by the strictures of that rule brought Klansmen out to enforce it. I could not comprehend a world where, even after the

U.S. Supreme Court struck down laws allowing housing discrimination, segregationists kept their version of order with dynamite— which was easy to find in a mining town like Birmingham—and the impunity that only collusion with the local police could bring. The Reverend Fred Shuttlesworth, a young civil rights leader and pastor of the Bethel Baptist Church in northern Birmingham, was blown from his own bed in the Christmas Day bombing of 1956. His church was bombed again and again, but the fire burned in him as much as around him.

I grew up, the son of reputable and important people of goodwill, with no real idea that the state of Alabama was at war with itself, that its most prominent city was ruled by terror for decades.

It was Shuttlesworth who talked Dr. King into coming to Birmingham in the year of my birth. It was Shuttlesworth who saw that the hatred in Birmingham was so barbaric it would shock the world into attention. It was Shuttlesworth who knew what would take place.

Birmingham was exploding all around, and I never knew.

Not as a child. Not of bombs or demonstrations or corrupt governments that did all in their power, and the power they claimed but did not deserve, to keep Black people in their place of disadvantage. I did not know of sit-ins at downtown department stores on the day I was born, or Shuttlesworth’s march to city hall the next day, or the arrests that would follow. I did not know of King’s incarceration or his letter from jail or a summer so intense its shocking images of snarling dogs and bludgeoning fire hoses would be seen on television screens around the world.

Only much later, when I read the words of Harrison Salisbury in The New York Times—they were considered fighting words in Birmingham back in 1960—did I begin to see.

“From Red Mountain, where a cast-iron Vulcan looks down 500 feet to the sprawling city, Birmingham seems veiled in the poisonous fumes of distant battles,” he began under the headline Fear and hatred grip Birmingham.

It speaks to me like poetry. It paints a masterpiece of a place I love and live and shines a light on all its flaws. It makes me fear the past, for if I look too deeply into it, I’m afraid of what I’ll see:

On a fine April day, however, it is only the haze of acid fog belched from the stacks of the Tennessee Coal and Iron Company’s Fairfield and Ensley works that lies over the city.

But more than a few citizens, both white and Negro, harbor growing fear that the hour will strike when the smoke of civil strife will mingle with that of the hearths and forges.

It speaks to me like poetry and truth and pain and premonition. Because I know now what will come for this city that tore itself apart. I read it, I can see it now. I can almost live it. And I dread where this journey will lead.

Salisbury’s story was legendary when I went to work in the newspaper business in Birmingham much later. It said the things few locals were willing to say, in a way that embarrassed chamber-of-commerce types and prompted the powerful to decry “outside agitators.” It said what could not or would not be said in civic clubs or between the stained-glass windows of white churches. It told truths that dared not be spoken in the oppressive censorship of the mid-century South:

Every channel of communication, every medium of mutual interest, every reasoned approach, every inch of middle ground has been fragmented by the emotional dynamite of racism, reinforced by the whip, the razor, the gun, the bomb, the torch, the club, the knife, the mob, the police and many branches of the state’s apparatus.

In Birmingham neither blacks nor whites talk freely. A pastor carefully closes the door before he speaks. A Negro keeps an eye on the sidewalk outside his house. A lawyer talks in the language of conspiracy.

Telephones are tapped, or there is fear of tapping. Mail has been intercepted and opened. Sometimes it does not reach its destination. The eavesdropper, the informer, the spy have become a fact of life.

I always wondered how so many otherwise courageous, decent men and women could look away, blind or oblivious or numb to the injustice surrounding them. It never dawned on me to look at my own home.

Salisbury’s thunderbolt of a story appeared in the Times on April 12, 1960. A few weeks later, my dad climbed into his pulpit at Alabaster Central Methodist Church, as it was then known, and preached a sermon about the horrors of the world.

His sermon was called “Where Is God?” and was based on a psalmist’s cry. He began by relaying a conversation:

Some time ago a group of men were talking. They were not talking about the bills and inventories that they had. They were not talking about the problems of their respective jobs. They were talking about the problems of the world—Katanga, Cuba, Vietnam and the many other problems that face the world. Finally one of the men just burst forth with the agonizing cry: “Where is God? Where has God gone?”

In the margins he scribbled notes. “Near East. Cambodia. Korea. Guatemala.”

Not Birmingham. Not among the bombs, or the whips, or the blades, or the politicians pandering in the name of God to a confused and hateful population. Not so close to home.

“Where is God?” I cannot help but think it a good question, for God is not in a sermon spoken from a pulpit in the shadow of Bombingham in the age of hatred and fear. Not even with the words of the Psalms and the great theologians. There is no mention of rights or race or wrongs in this church a half hour from Bull Connor’s office in Birmingham’s city hall. No mention of beatings or lynchings or the inhumanity of racism.

“Problems” are easier when they are foreign and far away, the sins simpler to hate when they are academic and theoretical. The omissions are glaring and the references, if they exist at all, veiled and vague.

The real problems were never foreign and far away. They were there in the courthouses that denied Black people the right to vote, there in the pews, where uncomfortable silence apologized for the hate of the Klansmen, who proclaimed it “Christian” to stand against equality for all. It was there in Birmingham, where powerful men argued that church was no place for integration. It was there in Alabaster, in my father’s own church, and at his alma mater, Birmingham-Southern College.

Salisbury talked about BSC in his story, too. And it surely would have struck home with my father, for Birmingham-Southern was like a friend to him. It is a Methodist liberal arts college and headquarters of the North Alabama Conference of the Methodist Church, the regional ruling body of the church to which he was so committed. He loved the rolling hills of that campus, and took his family there every chance he got. He sang for the bishop’s choir there, and attended conference sessions in its arena. He parked there to walk to Alabama football games at Legion Field, the old gray lady once known as the “Football Capital of the South.”

The real problems were never foreign and far away. They were there in the courthouses that denied Black people the right to vote, there in the pews, where uncomfortable silence apologized for the hate of the Klansmen.

The president of Birmingham-Southern College in 1960, Henry King Stanford, was under intense pressure then to expel a young white student who dared to participate in sit-ins supporting the civil rights of Black people, Salisbury wrote. Stanford refused to rush to judgment, and stood by Thomas Reeves, the twenty-one-year-old student and part-time preacher.

“In Birmingham this kind of courage does not come cheaply,” Salisbury wrote.

He went on to quote an anonymous Birmingham citizen about the pressures to remain silent.

“You weigh the situation. You take the counsels of caution. You listen to the voices which say don’t rock the boat,” the unnamed person said. “But finally the time comes when a man has to stand up and be counted.”

If not then, well, when? If not from a pulpit, then where? The words of Dr. King ring in my head:

I came to Birmingham with the hope that the white religious leadership of this community would see the justice of our cause and, with deep moral concern, would serve as the channel through which our just grievances could reach the power structure. I had hoped that each of you would understand. But again I have been disappointed.

Disappointed. Again.

________________________________________

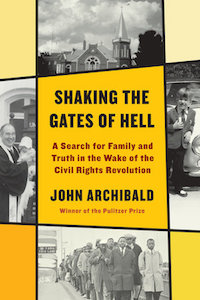

Excerpted from SHAKING THE GATES OF HELL: A Search for Family and Truth in the Wake of the Civil Rights Revolution by John Archibald. Copyright © 2021 by John Archibald. Excerpted by permission of Alfred A. Knopf, a division of Penguin Random House LLC. All rights reserved. No part of this excerpt may be reproduced or reprinted without permission in writing from the publisher.

John Archibald

John Archibald is a journalist for The Birmingham News, where he has been a regular columnist since 2004. In 2018, Archibald was awarded the Pulitzer Prize for Commentary. He lives in Birmingham, Alabama.