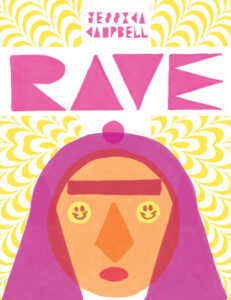

“Growing Up As a Girl in the Church, I Felt My Position on Earth Was to Serve Men.” A Conversation With Graphic Novelist Jessica Campbell

The Author of Rave Talks to Nicole Georges

Jessica Campbell (Rave) and Nicole Georges (Fetch) spoke to one another as part of D+Q Live, a spring event series by the graphic novel publisher Drawn & Quarterly. The conversation centered around the release of Rave—Campbell’s mordant and striking tale of a young woman coming of age within an evangelical, small-town community.

Both authors spoke about the risks of telling stories informed by truth, the grueling process of editing comics, and their respective relationships with their tumultuous religious backgrounds.

*

Nicole Georges: Did Lauren, the main character, come to you or did the events come to you first?

Jessica Campbell: The events came to me. I knew I wanted a protagonist that’s not exactly me, but I picture her as this passive person to whom events are taking place and she’s responding to them based on these voices that she hears through her friends or through church or whatever. So it was really the events that came to me first, but I knew I wanted that kind of character at the center of it.

NG: I was going to ask you where you end and she begins? What parts of your story do you see in her, or the people around her?

JC: Well, I think there’s much of this that’s coming from my own biography or my own upbringing in the church, my friends and situations that happened over the years. One of the dominant feelings that comes to mind when I think about my own adolescence is this feeling of immense insecurity and an immense lack of confidence, and feeling like I wasn’t even entitled to my own opinions.

That, to me, is central to this character, to the transformation that she goes through over the course of the book.

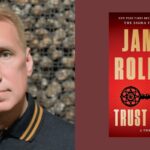

From Rave

From Rave

NG: I want to talk a little bit about the research that you did for this book, and what it was like to be around you during the three years that you were creating this book. I know you had to go to some dark YouTube places to write the dialogue as spot on as you did.

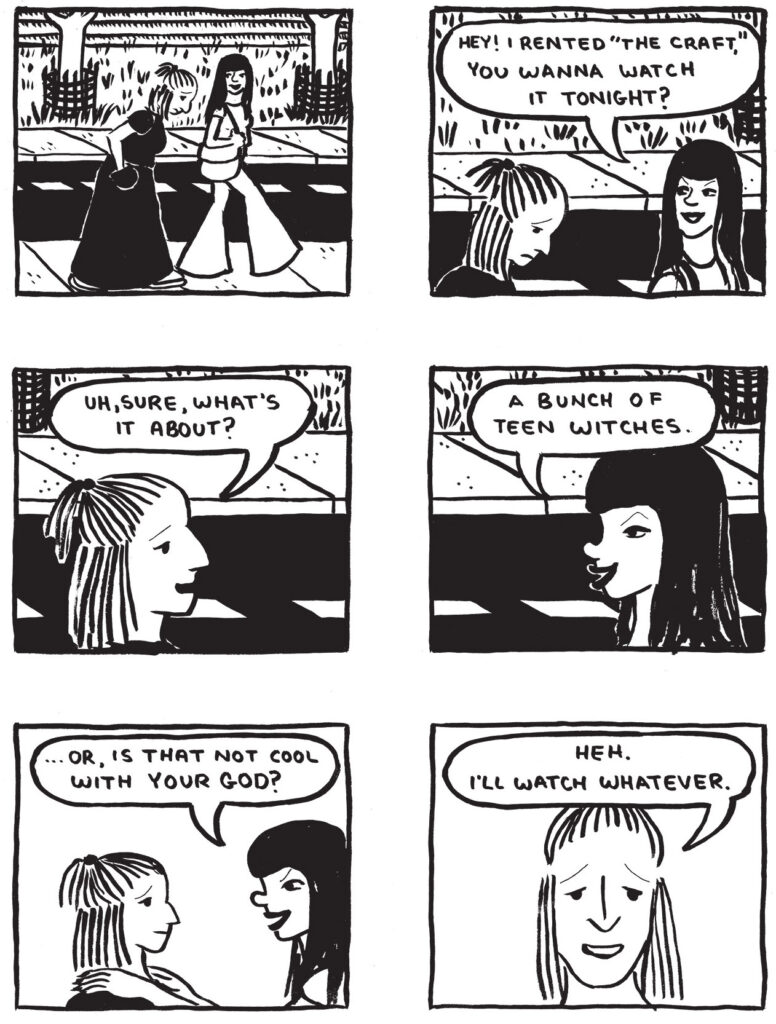

JC: A lot of the book is sermons or people—the youth minister, the pastor, or another kind of guest pastor—speaking. There’s such a particular cadence to it, at least in the States, and there’s something very powerful about that. It’s very evocative, and hearing someone speak that way makes me feel kind of queasy, but I wanted to be able to capture it as accurately as possible.

However, it’s been a long time since I’ve attended church regularly, so I went to YouTube and did some deep dives. I was specifically looking at sermons about women and girls and sex and things like that. I was triggering myself listening to them, but it was helpful. I realized one guy just kept repeating himself over and over again. Like, “You feel me? You feel me?” There’s this trance-like facet to it.

From Rave

From Rave

NG: I want to geek out for one second on your process. I just feel so strongly about editing in comics. And I know that you have so much experience as a reader, as somebody who worked at D&Q, as a writer, and a professor. I want to know what your editing process was like, and how important editing was to you on this project?

JC: Editing in comics seems extremely difficult to me. Especially if you’re writing a longer form book, you can’t just go back and put another panel in page ten, you have to put in multiple pages to edit anything. Previously, I just worked directly from thumbnails. Or an outline, then thumbnails, and then the final book. But I wanted the dialogue to feel real. I wanted the pacing to be a little bit slower than in some of my previous work.

So, I had conversations with a couple of cartoonists—Nick Drnaso, who did Sabrina, and Anya Davidson, talking specifically about her book Lovers in the Garden. Both of them, for those books, wrote prose scripts, and then thumbnails, and then moved into a final stage. I’d just been hesitant to work that way, because I know Lynda Barry just puts pen to paper, and then it’s like magic. Or Chris Ware, similarly, doesn’t outline anything. And they’re two of the greatest living cartoonists.

For me, having this extra layer of editing started with point form notes, and then prose expanded from there, before moving on to a script. It made the book a lot stronger than I’d been able to do previously.

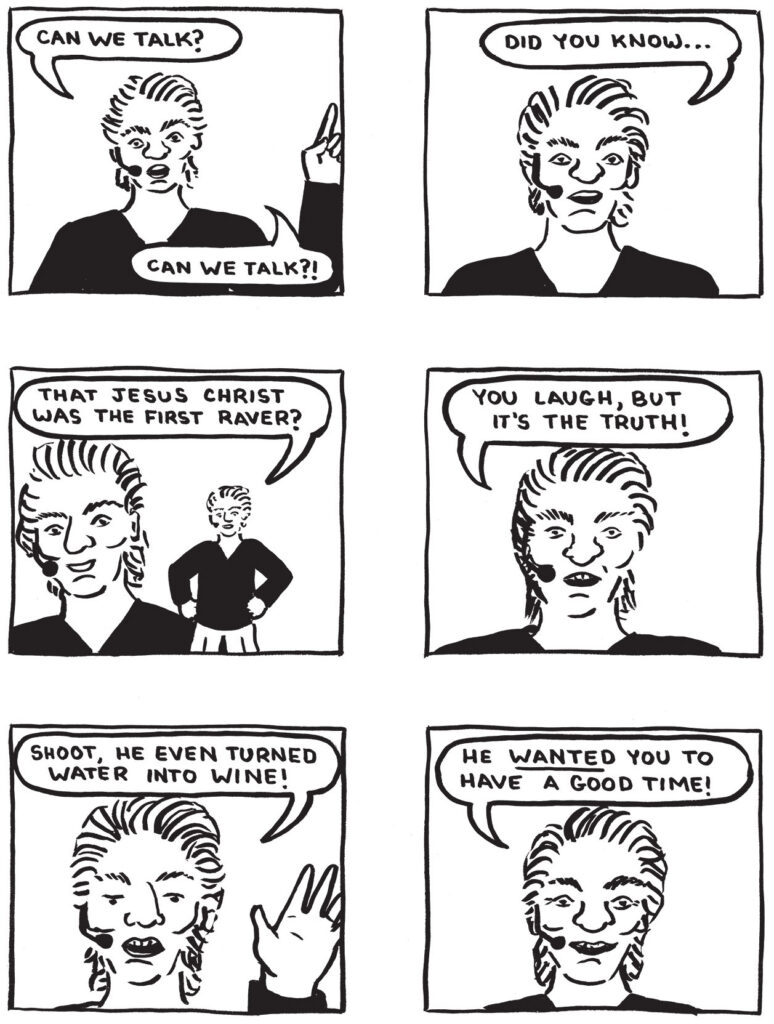

From Rave

From Rave

NG: If you could go back in time, is there anything you would tell your teen self? Or if you, as an adult human, could go and talk to Lauren the character, what would you say?

JC: Just that things can get better. That you can start to feel comfortable in your own skin. My life has a lot of problems, and objectively in the world, there are a lot of problems, but the idea that I got to spend time at Drawn & Quarterly and now have this book published by them, and I’m exhibiting my work… sometimes I wake up and I’m like, “Oh, I have the life that I envisioned for myself.” And that’s really amazing.

Sometimes when you’re living as a teenager, in a cloistered environment, in a small town, it doesn’t feel possible to freely live the life that you want or love the people you love. But I think it is possible.

From Rave

From Rave

NG: Let’s talk about your drawing technique, your materials, your process. We talked a little bit about the writing and editing process, but what materials did you use? What kind of paper did you use? How big did you draw? That’s important too.

JC: I drew this on 11 x 14 Bristol paper. It’s great for cartooning. You can get it in either a smooth surface or vellum, which is a little bit more toothy. I like the vellum textured Bristol. I use a normal HB pencil, and a lot of the inking I did with a Pentel Pocket Brush, which I like because it’s transportable. It has bristles as opposed to a Faber-Castell brush pen, which has a long felt tip.

I used this to do the lettering, and that’s because I was using a micron for the last book and the lettering just wasn’t thick enough. I also used some India ink and a nib, but that’s about it. Pretty cheap materials for the most part.

From Rave

From Rave

NG: What kind of permissions, if any, did you need to acquire? Or is it allowable to simply change some names and locations and go ahead and tell your story?

JC: I got no permission from anyone. There were some specific incidents that I had in mind —some traumatic things like deaths that happened in my periphery, and to people that I cared about. It’s the sentiment of some of those experiences, but not any direct references to them. I realized as I was writing the script that, inevitably, people were going to ask me, “How much of it was autobiographical?” Initially in the first draft, there was stuff with the parents in it. And then I realized, “Oh, I don’t want to hurt my mom.” Because I was writing them as fictional characters, but it seemed inevitable that they would think about it as them represented on the page, so I cut most of that out.

NG: I always change names. I make composite characters where I need to switch up people’s details. Because you just have to think, what’s the emotional truth of the story? And what’s important to the story? This isn’t journalism, necessarily.

JC: Exactly. Most of these characters, like Mariah, are amalgams of different people. Even people like the biology teacher, that’s definitely referencing my own experience as a teacher, where I’m cracking jokes and everyone’s looking at me stone-faced. So there are parts of it that are autobiographical in that way as well.

NG: When you’re working on a book, do you put other types of art aside? Or do you work on lots of different things at once?

JC: I find it impossible to work on lots of things at once, I feel like I have a really bad work/life balance. I’m either working on something and not doing anything except for working on the project, or I’m laying on a couch, but I don’t do anything in the studio. And likewise, I find it impossible to switch between making comics and then making fiber work or whatever. So at the moment I’ve been focusing more on installation and fiber projects. Once I’m fully recovered from this book, I have a sort of hybrid project that’s going to come up next year that’s part comics and part installation.

From Rave

From Rave

NG: So this final question asks, how did you get away from the church?

JC: I wish that it was a clear and decisive break, but really it was something that kind of crept up on me over the course of many years. I got this job working at Munro’s Books, where I was asked to work on Sundays. Then I had some interactions with my family, where I was questioning certain things about church doctrine, and was dismissed in a way that made me feel like thinking critically about the church was not allowed.

Combined with having a lot of friends who weren’t in that environment, who I knew were good people, and maybe some Ouija board demons, it all started coming together. Growing up as a girl in the church, I felt like my position on earth was to serve men, and the idea that I only get to live one life and I’m not even entitled to a full life or agency over my body, was so distressing to me that it felt like it couldn’t be legit.

It was a really long, slow process to fully leave. And I don’t know that there was even a moment where I was like, “I don’t believe in this anymore.” It just kind of happened over time.

______________________________________

Rave by Jessica Campbell is available now via Drawn & Quarterly.