Group Sex Therapy at the Local Synagogue?

On Reading the Sexy Bits of the Bible

Ruthie, a professional sex educator, was trying to help us out a bit. “Get into groups of three or four,” she instructed us, “and describe a significant spiritual experience you’ve had. Describe what it felt like. Then look for where your stories use similar language or images and try to create a definition of spirituality.”

We’d been gathering every other Tuesday in the large mezzanine of the historic synagogue we rent out for our church gatherings to discuss sex and spirituality. For many of us, just grouping the two words “sex” and “spirituality” felt uncomfortable, almost oxymoronic. It seemed like something you’d hear from a creepy 1970s Southern California guru—some lech in linen drawstring pants talking about self-gratifying nonsense.

Ruthie manages to talk about sex in such a non-awkward, matter-of-fact way that it had put most of us at ease almost immediately. She is a compulsive knitter, has the strong back and shoulders of a former competitive swimmer, and is almost as tall as I am. She also is the proud owner of what I consider to be the nerdiest tattoo at church, which is saying a lot since at least two people at HFASS have Flannery O’Connor–related ink. On Ruthie’s chest is a drawing of an old prop plane surrounded by a diagram of lines and equations, representing all the forces that act on an airplane when it’s in flight: lift, weight, thrust, and drag.

That night, we had grouped ourselves in threes according to Ruthie’s instructions: in one group a retired divorced librarian, a young single teacher, and a gay partnered accountant; in the next, a married social worker in her twenties, a widowed lesbian factory worker, and a straight baby boomer. We described what our spiritual experiences had been like, and reported to the larger group the similarities in our responses:

That which is beyond expectations.

That which brought a freedom from something (like fear or shame).

Awe—beauty or discomfort.

Support—even if it was uncomfortable, there was still something holding us.

Transformation—a radical acceptance of life and getting outside of one’s self.

Mystery—hard to put into words.

That which brings us both deeper into ourselves and lets us be outside of ourselves at the same time.

Reagan broke the silence: “Sounds like the kind of sex I’d like to be having.” Everyone laughed in solidarity as we realized that all of these responses about good spirituality did sound a lot like good sex.

It was a relief to laugh knowingly together about sex, especially since so many people in that room struggle with shame over sexuality.

But not Sheila, a close friend of our congregation. Sheila is shameless. She grew up with five older, overprotective brothers on a family farm. When her brothers realized that their teenage little sister was sexually active (she was blatantly unapologetic about this), they tried to keep her out of more trouble by piling up outdoor chores for her. Sheila developed a deep brown tan that tops her natural olive color, and which she maintained through young adulthood by remaining a lover of the outdoors.

“I think my skin is beautiful,” she is known to say, without a trace of embarrassment. Even now she makes her living outdoors, working as a zookeeper and specializing in various sheep and oxen from the Middle East. She and her partner, Mike, met at work. Apparently she finds time every day to flirt with him. If nothing else, she sends him sexy text messages that tell him where she wants to meet up later and what she wants to do to him. They compete with each other in a sweet and slightly old-fashioned way: by seeing who can write better poetic lines about the magnificence of the other’s body using only images they see at work. Sheila gets lots of jokey midday texts comparing her breasts to the baby gazelles in the zoo nursery.

When another kid my age at church told me there was a book in the Bible about sex, it felt as though they admitted that there was a book in the Bible about cocaine.

I’ve often wondered what exactly people mean when they say someone is “in their body,” but even while I am still not sure of the answer, I know that Sheila is an example. She is self-possessed when she moves, as if in ownership and control of each bone and muscle, not just defaulting to the ones absolutely needed for ambulation. Like she is aware of each inch of her and delights that each inch of her is hers. Like she is both science and magic. It’s not vanity. Vanity is thinking everyone around you considers you the prettiest. What Sheila demonstrates is aplomb.

Sheila and Mike appear to have none of the sexual shame that seems to plague most of my congregation. They aren’t married and yet it never once dawned on them to hide that they are, indeed, lovers. They take great delight in each other and in their own selves, as if the attraction they have for each other has turned into a deep appreciation for and confidence in their own selves, personally, physically, and sexually. They belong to each other, body and soul, and yet remain distinct individuals.

I began to see Sheila and Mike as a standard of body positivity and sex positivity—that is, at the same time deeply spiritual. Their relationship to sex, to each other, and to themselves seems integrated and whole, a stark contrast to so many of my parishioners who were raised in “Bible-believing” churches. But why is it that Sheila and her lover seem to be exceptions to this rule? How is it that they seem so free from the shame of having a body, and a sexual body at that?

Well, it is because Sheila is not actually someone I know. She is the narrator of a very long, very hot erotic poem, a poem in which she expresses her sexual desire without shame, expresses the love of her own beauty without qualification, expresses a longing for and an appreciation of her lover’s body without apology. Where might you find this poem, you may ask?

You guessed it. The Bible. The b-i-b-l-e. The same book that brought you such sexual ethics as the rape of Tamar and “women, be subjects of your husbands” and “if a woman does not bleed on her wedding night, stone her” also brought you two unashamed lovers in an erotic poem called Song of Songs. Because the Bible, like sex and every other visceral experience, is never only just one thing.

When another kid my age at church told me there was a book in the Bible about sex, it felt as though they admitted that there was a book in the Bible about cocaine. So one Sunday afternoon, when I was alone in my room, I took out my Bible, the one whose cover featured pictures of hippies inside the big letters announcing “good news,” and found Song of Songs (mistakenly called Song of Solomon), eager to get some answers. But all I found were a couple of mentions of kissing and some guy comparing a girl’s breasts to animals, which felt weird. I was no closer to cracking the sex code than before.

Now I know. The Song of Songs tells a story about sex, but it’s not porn. It’s erotica. It’s more about desire than it is about coitus (forgive me for even using this word). But it is not just about desire in general. It is primarily about female desire. And as Carey Ellen Walsh says, rightly, it is “shocking that an entire biblical book is devoted to a woman’s desire . . . It is truly subversive, offering a dissonant voice of the canon, that of a woman in command of and enjoying her own sexual desire.”

All throughout the poem, Sheila says beautiful things like this:

As an apricot tree stands out in the forest

My lover stands above the young men in town

All I want is to sit in his shade

To taste and savor his delicious love

He took me home with him for a festive meal

But his eyes feasted on me!

If it’s true that the church sees sex as its competition, then Song of Songs is like if the competitor set up camp inside the church’s borders.

Here we have nature, feasting, sensuality, sexuality, and desire . . . in the Bible. But since Song of Songs is a poem primarily about female sexual desire it should surprise no one that for most of its history, in the hands of male clergy, scholars, and theologians, it was not seen as such. It was read as allegory.

A rabbi from the second century, Rabbi Akiba, famously said of Song of Songs, “All the writings [of Israel] are holy, but the Song of Songs is the Holy of Holies.” He was saying that the writing in Song of Songs was not an erotic poem but a mystical key for understanding the love of God.

“For the next two thousand years,” writes poet and scholar Alicia Ostriker, “rabbinic commentary would interpret it as an allegory of the love between God and Israel.” Subsequently, Christians would read the same text as an allegory of Christ’s love for his church. If it’s true that the church sees sex as its competition, then Song of Songs is like if the competitor set up camp inside the church’s borders. Religious leaders bent over backward to deny Song of Songs its identity.

This happened pretty early on, beginning with a guy named Origen. Origen lived in Alexandria in the 200s and was a prolific Christian writer, thinker, scholar, and preacher. Origen reportedly wrote ten volumes about Song of Songs, much as Augustine—the guy who had such profound hangups about his penis—spent his career writing volumes about how Adam was able to control his erections before “the fall.”

Origen had a few lifelong hangups himself. (Surprise, surprise.) He was so tortured by his own sexual desires that he took the matter into his own hands, literally. Origen took seriously the Platonic notion (often repeated in some of Paul’s writings) that the spirit is of a higher plane than the flesh, that the body is an enemy of the soul. So rather than be plagued by sinful sexual desires, he castrated himself. That’s commitment.

Self-castration for the purpose of avoiding temptation seems so extreme, and yet it differs only in degree from insisting that women hide their bodies so that they do not tempt men, telling hormone-soaked boys that they have to avoid even thinking about sex, and describing sex as sinful and dangerous and toxic outside of heterosexual marriage. All of it smacks of the bullshit Cindy’s pastor barked about: “transcending our sinful bodies.”

But the fictional woman I’m calling Sheila seems to embody none of this separation between the flesh and the spirit. It’s why I find her poetry to be so freeing. She is so different from most of the people I encounter, so different from myself.

The writers of the New Testament lived in a deeply Hellenized culture, one in which Greek thinking held sway, including the belief that the body was corrupted and that only the spirit could be holy. There were even forms of Christianity early on that clung so deeply to this idea that they refused to believe that Jesus even had a body at all. He just seemed to, they said. And the Greek word for “seeming to” is the root of the word docetism, which describes a belief that denies the Incarnation—that little thing about who Jesus was. But orthodox thinking holds that Jesus is God made flesh. Flesh. Carne. Meat. So docetism was eventually ruled heretical.

Why, then, did Sheila’s erotic love poem become something Christians believe was written by King Solomon about Jesus’ love for the church? Marvin Pope explains it in his book Song of Songs: “Origen combined the Platonic and Gnostic attitudes toward sexuality to . . . transform it [Song of Songs] into a spiritual drama, free from all carnality.” How bizarre that a religion based on the merging of things human and divine—a religion based on God choosing to have, of all things, a human body; a faith whose central practice is a shared meal of bread and wine that we say and even sometimes believe is the body and blood of Jesus—could develop into such a body-and pleasure-fearing religion.

I find myself outraged at how the erotic nature of Song of Songs has been domesticated, forced into a tame little allegory, and how the anti-body, anti-woman, anti-sex teachings of the church we’ve discussed have hurt me and so many people in my care. It’s infuriating and makes me want to dismiss huge chunks of Christian teaching and history.

How is it possible that we can reliably hurtle thousands of tons of human and metal through the air?

But then I think, Hold on. While I bristle at the interpretive move men have historically made regarding the one book in the Bible that is quite possibly written by a woman—and a sexually expressive woman at that—I remember how Ruthie taught us that sex and spirituality are inextricably coupled. Those who influenced the course of biblical interpretation may not have intended to make the text of Song of Songs even richer by pairing sex and the spirit—yet here we are, the Holy of Holies.

Because, again, the similarity between the language we used in that discussion group to describe spiritual experiences and the language we used to speak about really mind-blowing sex—the kind of sexual experience that Sheila embodies, unselfconscious, transcendent—was startling.

That night we participated in Ruthie’s exercise, we already knew the conversation was about spirituality and sex, so I wondered if that might’ve been why our answers skewed in a sexual direction. The next day I went on Twitter and asked, “What words or images would you use to describe a profound spiritual experience you’ve had?” Here’s a small sampling of the replies.

Amazed and confused. Then grateful.

I was placed in a bubble of warmth and a calm voice told me everything was going to be okay. My mind was changed about God then.

Warm. Unclenched shoulders. And then completely terrifying and bewildering and embarrassing as soon as I step out of the stillness and try to understand what happened. Comfort, freedom, release.

Home: being welcomed into a space that means I don’t need to make or do anything, but I can just be who I am at this moment.

Restorative.

Feeling deeply clean.

Overwhelming, tearful, burden lifting, joy.

No words . . . just the feeling of a great opening and inner spaciousness.

Here’s a thought experiment. Imagine if Sheila—so in her body, so free from shame—were asked to describe what it’s like to have really great sex. What might she have said? Would she have used words and phrases similar to those listed above? I can’t help but think so.

*

Back in the mezzanine at church, I was staring at Ruthie’s tattoo of the old prop plane when I remembered why she’d gotten it in the first place. She’d told me that she chose it because of her love for math and physics, and how, while those things explain how most stuff works, they don’t explain everything.

“How is it possible that we can reliably hurtle thousands of tons of human and metal through the air?” she said. “We should just fall to a fiery death. Humans have only ever dreamt of flight and have written myths about it for millennia. But now we do it every day without even giving it a thought. Air pressure doesn’t really begin to account for it. It’s also magic. So my tattoo is my reminder to sit back and wonder at the magic of it all.”

Maybe the same could be said of being human. There’s a classic Star Trek episode in which the crew encounters a highly evolved life-form that is basically pure consciousness, and this life-form derisively and yet also accurately describes humans as “ugly bags of mostly water.”

We humans are ugly bags of mostly water. We are a scientifically understandable combination of chemicals and particles—and, yep, lots of water.

But you cannot understand humans by simple formulas, scientific, religious, or otherwise. Because there is also magic. We can determine the amounts of oxygen, carbon, hydrogen, calcium, and phosphorus that constitute a human body. But when we draw a diagram of the forces acting upon these bodies, there is still the one thing we can never solve for: The magic. Spirit. Soul. The imago dei. The breath of a living God who gives us life. Yah. Weh.

Too often, the diagram that religion draws up for explaining sex takes the snake’s-eye view—it names only the physics of fear, threat, and control, but none of the magic. Likewise, media and advertising thrust the commodification of sex our way, and sex becomes either something to trade in or just another aspect of life in which we are judged and found lacking. But neither of these approaches is enough. Neither points to the whole truth. Because there is also magic.

This magic is what God placed in us at creation. It is the spark of divine creativity, the desire to be known, body and soul, and to connect deeply to God and to another person. This magic is the juiciest part of us, and the most hurtable. This magic was breathed into us when God emptied God’s lungs to give us life, saying, “Take what I have and who I am.” This magic is what snakes seek to darken with shame. This magic was what was sanctified for all time and all people when Jesus took on human form and gave of himself, saying, “Take and eat, this is my body given for you.”

__________________________________

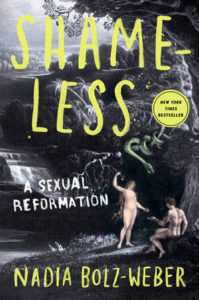

From Shameless: A Sexual Reformation. Used with permission of Convergent Books, an imprint of Penguin Random House. Copyright © 2019 by Nadia Bolz-Weber.

Nadia Bolz-Weber

Nadia Bolz-Weber first hit the New York Times list with her 2013 memoir—the bitingly honest and inspiring Pastrix—followed by the critically acclaimed New York Times bestseller Accidental Saints in 2015. A former stand-up comic and a recovering alcoholic, Bolz-Weber is the founder and former pastor of a Lutheran congregation in Denver, House for All Sinners and Saints. She speaks at colleges and conferences around the globe.