Grant Faulkner on Capturing the Essence of a Short Story

“It’s the writer’s job to capture essences in words.”

The following first appeared in Lit Hub’s The Craft of Writing newsletter—sign up here.

*

Japanese author Yasunari Kawabata was obsessed by capturing the essence of a story. Essence as the intrinsic, indispensable quality that characterizes something, an extract that holds the fundamental properties of something in a concentrated form, a perfume, a scent.

Perfume comes from the Latin “per,” meaning “through,” and “fumum,” or “smoke.” Perfumes have been traditionally made by extracting natural oils from plants through pressing or steaming. In steam distillation, steam is passed through plant material, turning the plant’s oil into gas, and then the gas goes through tubes, where it is cooled and liquified. The oils are collected, then they’re blended together by a master, called a “nose,” who creates a scent with other ingredients and mixes it with alcohol. It’s a meticulous process that requires an intense patience and attunement to nuance to find the rare redolence that exists in quintessence.

In his most strenuous effort to capture the essence of a story, Kawabata—who won the Nobel Prize in 1968—turned his acclaimed novel Snow Country, into an 11-page story, “Gleanings from Snow Country.” Kawabata completed the story just three months before his suicide in 1972. “Gleanings” pulls scenes almost intact from the novel, but Kawabata does not offer a condensed retelling, as one might expect; instead he becomes more suggestive.

“Gleanings” moves without backstory, without the context of the novel, which centers on a story of two people meeting on a train in a doomed love affair. “Gleanings” defines these characters as being more like particles floating through space, unattached, not moored in a particular world or pulled forward by a particular trajectory or fate. In his spare style, Kawabata intensifies images and excavates new facets of his novel.

Why did he rewrite Snow Country as a short story? Did he suddenly realize that the novel, all of those pages, all of those words, didn’t serve the story—that the truth of the story required a smaller space, to be passed through smoke like a perfume? The novel was already written with brevity, focused around essence. In fact, Fred Chappell describes the novel as full of haiku in prose form. Did Kawabata realize at that point in his life, when his eventual suicide must have been on his mind, that we carry only a handful of essential images with us?

The title is interesting to me because “Gleanings from Snow Country” isn’t a new title but hearkens back to the novel. He could have recast the images as an entirely new story, except he wasn’t interested in a new story. I wonder if Kawabata was telling us that the “gleanings” matter more—that the gleanings are the essence we need to pay attention to. His miniaturization intensifies the isolated images. He works with understatement and ambiguity as if they are part of his color palette. He writes behind a veil. Elusiveness permeates. Ambiguity and suggestiveness are tools to capture essence, he seems to say.

The word essence carries the connotation of mystery because it’s often viewed as something that’s hidden. One must pay acute attention to realize the quiddity of something. Or, perhaps essences don’t lurk within things so much as we move through essences in life as we move through air, breathing oxygen without even thinking about our need to breath oxygen.

When I look up from my computer, I see my dog sleeping on the couch, I see an oak tree outside my window, I smell a beef stew simmering on the stove. I’m taking in the world through its essences, as if detecting essences is a sense unto itself, my senses and my consciousness and my memories determining that the tree is an oak tree and not a palm tree or a cherry tree and that my little dog is not a cat. Essences belong to the “flesh of the world,” as the philosopher Merleau-Ponty said.

As you read you feel the story’s weights and measures, taste its consonants, absorb the essence of it in ways you might not even be able to name.

We search for essences. It’s the writer’s job to capture essences in words. The senses come into play in a new, more intense, more nuanced way. A smell combines with the angle of light, which combines with a car door slamming outside, which combines with a memory that creates a mood, a moment on the page.

The music of language is a concentrating force as well. It creates intimacy with the rhythms of a writer’s imagination, its cadences communicating hints of irony or sincerity, humor or distress. The sounds give shape to the story. As you read you feel the story’s weights and measures, taste its consonants, absorb the essence of it in ways you might not even be able to name.

The search for the essence of the essence drove Kawabata. He also wrote miniatures, “palm-of-the-hand stories,” which he said “flowed from my pen naturally, of their own accord.” It was the form he felt encapsulated his art, the one where “the poetic spirit of my young days lives on.” One might, in fact, say that his novels are essentially linked miniatures.

Miniatures allowed Kawabata to focus on ambiguity as a narrative tool. The ambiguity creates different contours, curves that are spacious and deep because they open into deeper meaning rather than weaving connections and explanations. The irresolution of Kawabata’s stories speaks to the epic nature of our interior lives.

In his story “The White Flower,” a writer tells his lover, “You bring a beauty like a fragrance that you can’t see with the naked eye, like the pollen that perfumes the spring fields. How shall I write it?” A writer knows that all of the words, all of the time in the world, can’t possibly describe such beauty, so he has to rely on a less perfect, a less comprehensive approach: “Put your soul in the palm of my hand for me to look at, like a crystal jewel,” he says. “I’ll sketch it in words.” A person’s soul, their beauty, can only be captured in its distillation.

“The poet gives us his essence, but prose takes the mold of the body and mind,” said Virginia Woolf. I think Kawabata might have been in search of a way to do two things at once: to give the body and mind of a story while also giving its essence, its poetry. Only by using the tools of brevity—such as distillation, condensation, and ambiguity—could the corpuscular be transformed into gleanings. Essence is about attentiveness. You deepen what you regard.

Even God knows the story can’t be told in its entirety. A profligacy of words soon disorients. Rococo flourishes end as fulsome decadence. It is absence that spawns the fundamental mystery of life. Subtle gestures, dashing glances, unspoken words whisper through our days, a beguiling puzzle. No explanations, please. Listing a dish’s ingredients reduces its taste. Keen images pique the palate best. We drift, rush, falter, and flounce, following scents. A flicker of light appears, a thunderclap in the distance. Illumination, short-lived, then gone, or so it seems. We can only touch nuances and wonder. And then, that final breath.

___________________________

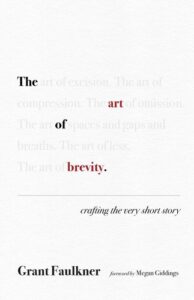

Excerpted from The Art of Brevity. Republished with permission of University of New Mexico Press.

Grant Faulkner

is the executive director of National Novel Writing Month (NaNoWriMo) and the cofounder of 100 Word Story. He has published two books on writing, Pep Talks for Writers: 52 Insights and Actions to Boost Your Creative Mojo and Brave the Page: A Young Writer’s Guide to Telling Epic Stories. His essays on creativity have been published in the New York Times, Poets & Writers, LitHub, Writer’s Digest, and The Writer. He’s also cohost of the podcast Write-minded.