On May 28, 2013, I tweeted: Spent the weekend just wandering around outside, caramelizing things with my crème brûlée torch.

And then on August 28, 2014, I tweeted: Just learned this morning that my Imaginary Intern is an ethnic Chechen. I was being facetious, of course, and I wasn’t sure if the Imaginary Intern had even seen the tweet, because we were both very busy that morning, off doing our separate things. I think he was reviewing and archiving childhood crayon drawings and digitized 8-millimeter birthday-party footage that my dad had shot in the early sixties, and I was, uh . . . you know what? . . . I think this was a period of time when I’d become, like, mildly obsessed with Spaten lager beer . . . so I’m pretty sure that that day I was out looking for a place that sold it by the case. But it turned out that he had indeed seen the tweet, because once the two of us reconvened later that evening, he asked me, “What ethnicity do you actually think I am?” And I don’t remember exactly what I said, probably something like, “Oh, you’re a paracosm.” Or “Oh, you’re a quasi-autonomous notional entity.” Or “You’re an apparition from Figmentistan.” Or something like that. Just kidding around with him. And I remember he said, very seriously, “I think I’m a teratoma.” And it took me a minute before I realized he was alluding to an incident that had occurred, I don’t know, some fifteen years ago when my mom had an ovarian cystic teratoma removed. I didn’t know what a teratoma was at the time, so I did some research and I discovered that it’s a kind of tumor that can contain hair and teeth and, in rare cases, eyes and feet, but much more commonly the hair and teeth, so I went out and bought a tiny comb and a tiny toothbrush (I think they were from a set of toiletries for one of those Troll dolls that I found at a Toys “R” Us) and I gave them to my mom at the hospital. And I immediately regretted the “gift”—I’d originally thought it was sort of cute and clever in a completely innocuous way, but then it just seemed like a creepy morbid attempt at humor at her expense, and I was really apprehensive that she’d be hurt and angry. And she so easily could have hobbled me with a glare or a pained aversion of her eyes if she’d wanted to . . . because I don’t think it was funny to her at all . . . I mean, she had two huge heliotrope bruises—one from a tourniquet they’d used to start the IV drip in her arm and one from a catheter she’d had on the dorsum of her hand—that made me wince when I looked at them, she was still nauseous from the anesthesia, and she was still in a considerable amount of pain from the surgery itself. But she just smiled at me, in that beautiful, gracious, indulgent way she has of smiling at me, the way she’s always smiled at me. This is the Noh mask of her immutable benevolence.

I said a little while ago when I was talking about how my mom drove me to the mall tonight that I don’t really like to talk to her when she’s been drinking and she’s driving over ninety miles an hour, because I don’t want to distract her. And I was just being facetious. And it was a glib, thoughtless thing to say. Just for cheap laughs at her expense. And I just want to say that my mom does not drink and drive. And as soon as I said what I said, I regretted it completely. And, Mom, I looked over at you and you could have just glowered at me, which would have ruined the whole reading for me, the whole night . . . but you didn’t. You just took it in stride. You just looked up at me, and smiled that beautiful, indulgent, luminous smile of yours, and went right back to your pork fried rice.

One stands up here, on a table in the middle of a food court, as one would upon a balcony overlooking a piazza thronged with swooning Fascists. And one becomes heedless, one becomes disinhibited, indiscreet . . . and one says all sorts of things one shouldn’t say—

(MARK’S MOM, as if on cue, reaches furtively across the table to snare MARK’S egg roll.)

MARK

Don’t eat mine, Mom.

(MARK and his MOM exchange a conspiratorial wink, as if this whole little pas de deux about the drunk driving, the ovarian tumor, and the egg roll had been predesigned to finally coax a reaction—any reaction—from the PANDA EXPRESS WORKER, who simply shrugs indifferently . . . whatever.)

MARK

I think one of the first things I ever wrote was a puppet play. Not a play that was intended to be performed using puppets, but a play intended to be performed for puppets—for an audience of puppets—for the stuffed animals and action figures in my bedroom. (So, given the fact that I still think that the ideal audience for my work is inanimate objects, a roomful of empty chairs actually constitutes a full house!) These plays, these productions, performances, whatever you want to call them, sort of bounced back and forth between dialogue and dance, and they were mounted in my room, as I said, and the audience would typically consist of my stuffed orangutan, maybe a G.I. Joe or two, and several dozen plastic Civil War soldiers. Many of the topics at play in these early works were those with which I’d been fixated since I was a little boy: Pietà sculptures, claustrophilia, fascism, flagellate protozoa, androgenized female Eastern European athletes, the fragility of persona, etc. And, as I said, there was dance. The choreography was spare, rudimentary. There were two basic movements that I’d perform simultaneously as I recited my monologues. I suppose in the way a sensitive child, say, in the Middle Ages, might see the threshing motions of men and women harvesting grain in the fields and make from that a formalized dance movement, a sweep of the arm could represent the eternal rhythm of the seasons, I repurposed two motions I’d seen adults perform many times in the milieu I grew up in. The first was a shifting of weight from my right foot to my left foot, back to my right, then to my left, back and forth and back and forth—this was a particular kind of swaying or shuckling I’d gleaned watching men preparing to hit a golf ball at the driving range or at an actual course. The other movement derives from women shuffling mahjongg tiles. I would extend my arms out in front of my body, palms down, and make circles with my hands, flat, horizontal circles, clockwise with my left hand, counter-clockwise with my right. I’d perform these movements as I recited my stammering, maudlin soliloquies and the rabid harangues to my plastic soldiers. I guess this was a kind of, of . . . what’s the word? . . . a kind of . . . liminal gesturing, a gesturing that announced that we were about to cross a threshold . . . that we were waiting . . . not knowing what’s next . . . not knowing what violence or calamity my words might bring down upon us . . . This was my little Totentanz . . . my little dance of death . . . something along those lines, I guess . . . And I loved putting on these plays very, very much, alone in my room, with my rapt audience of inanimate aficionados. And, honestly, I never wanted to do “more” with it . . . or become “known” for it . . . or pursue it as, y’know, any kind of vocation or career.

Which reminds me of something interesting . . . Soon after the Imaginary Intern left, I found a postcard from him. There was a photograph on one side . . . it was a close-up of a white skinhead and behind him was this black guy (whose face and torso were out of frame) sort of standing over him, straddling him, so that his penis was lying down the center of the skinhead’s shaved white skull, giving him, like, a penis Mohawk. And under the photograph was a caption that had originally read Stay relevant. But the Imaginary Intern had added, I guess with a Sharpie or something, the prefix ir- in front of the word relevant, so it read Stay irrelevant, meaning— at least this is my interpretation—don’t do anything, whether it’s having a friend drape his dick across your head or putting on little, sort of experimental USO performances for your plastic Civil War soldiers, or whatever—for the sake of becoming well known. Do the contrary. Cultivate your irrelevance, cultivate your gratuitousness. The Imaginary Intern had also stapled a clipping to the blank side of the postcard, presumably from some scientific journal like Nature or Cell, which had the headline “South Korean Microbiologist Discovers That Even Amoebae Fall into the Five Basic Archetypal Categories: Nerd, Bully, Hot, Dumpy, and New Kid,” the meaning of which, with regard to that photograph, I’m still trying to understand, even though I realize it’s entirely possible that he just stapled the clipping to the postcard as a way of saving the clipping—in other words, that he was just looking for something to staple the clipping to in order to file it, and just randomly grabbed the postcard, so that its contents were completely irrelevant. But I really, really doubt that, just given the way the Imaginary Intern seemed to deliberately generate—well, not generate . . . locate would probably be a better word—the way he seemed to very deliberately, very painstakingly, very precisely and rigorously locate signification in just about everything he did. But it’s a precision and rigor that only becomes apparent in retrospect. In fact, I would say 99 percent of things involving the Imaginary Intern only become apparent in retrospect. And he really did fervently believe—as do I—in this whole idea of staying secret, of shunning the spotlight. A friend of mine once suggested that someone make a documentary about the Imaginary Intern . . . set up cameras all over the house like in that movie Paranormal Activity . . . and I told the Imaginary Intern about it, and he freaked. He hated the idea . . . And I immediately regretted having told him about it. It was a huge mistake. And sometimes I think that that’s actually why he left. He just wanted to be completely off the radar, left alone, completely inconspicuous, completely off camera . . . I don’t know if he’d been abused in his life or what . . . but he just wanted to be able to relax and act as loony and as dorky as he wanted to without having to worry about what anyone else thought, and I think the idea of a documentary just really shook him up, it really spooked him. I think I mentioned before that I’ve tried to re-conjure his face from the configuration of cracks in the tile floor of other bathrooms. In fact, I was sitting on the toilet in the men’s room in the Nordstrom in this mall actually, and I thought I discerned his face in some craquelure on the floor, and I remember I was concentrating so hard on it, trying so hard to force a jumble of disparate features into a recognizable physiognomy, that I was actually straining, y’know, pressing in that way that can cause hemorrhoids, so I had to stop. I’ve had that sudden, that sudden frisson, that jolt of It’s him! many times, and I’ll squint and I’ll look from different angles and inevitably it’s a false alarm, it’s not him . . . and it’s . . . it’s a big, big letdown, it really is . . . it’s a shitty feeling.

But that’s what nonfiction is, people. Shitty feelings and encounters with death. And that’s why we’re here tonight.

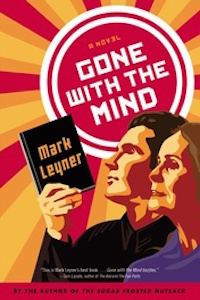

From GONE WITH THE MIND. Used with permission of Little, Brown and Company. Copyright © 2016 by Mark Leyner.