Christopher Chanticleer Norvald arrived at the East Venice Avenue bus station on October 22, 1987, clutching a bag of dirty laundry, a Walkman, and a seven-page letter—written all in caps, in pencil—to his grandma Oona from his mom. You couldn’t get any older or any whiter than downtown Venice on a weekday afternoon. It was cataclysmically tranquil. People moved there to die, comfortably and quietly, and if you had other plans then you were in the way.

To the north lay Tampa, sprawling and soulless; to the south, a no-man’s-land of half-drained swamps and gridded subdivisions. Inland was a crazy quilt of meth labs, migrant workers’ shacks, and citrus farms gone bust. The Gulf itself was always there, lazily brining the sunlight, but there’s only so much time you can spend floating in lukewarm brackish water on your back.

At times the boredom grew so punishing that the more sensitive Venice residents went quietly out of their minds: people took drugs at random and gave their life savings to mega-churches and drove head-on into interstate dividers. The month Kip got to town, one of his grandmother’s neighbors dug a hole in his backyard, as wide and as deep as the property line allowed, and tried to start charging admission.

The snowbirds reclining in their deck chairs by the shuffleboard courts down on State Street, needless to say, couldn’t have cared less about these occasional eruptions of swamp fever. They wanted anyone under sixty out of their line of sight—except when their lawns needed mowing, or their Winnebagos needed an oil change, or they wanted a cone of soft-serve on the beach. Sometimes Kip actually found it hard to breathe in Venice: the air felt thin, secondhand, oxygen-poor. The undead had triumphed over the living in Sarasota County sometime back in the seventies, and the victory was total. You could feel it on your skin.

*

Less than a week after their first hangout, from one day to the next, Leslie Z was gone from Venice High. The Powers That Be intended it as a temporary suspension, no more than a slap on the wrist—but he took it to heart, to Kip’s astonishment, and never went back. As Leslie told it, Principal Sennheiser’s motives were “crypto-political”; according to everyone else, he’d shown up to morning assembly in a pair of assless chaps. Kip couldn’t help but wonder how the Voglers had reacted to the news. He pictured them smiling up at their son from that psychedelic sofa of theirs, holding hands like college sweethearts, assuring him that all was for the best. But it was just as likely that he never told them.

He dropped by Kip’s house the day of his suspension, dressed normally again—normally for Leslie, at least—in green jeans and a Morbid Angel T-shirt. Nothing about him indicated what had just gone down. Kip’s social anxiety kicked in instantly: he was terrified that Leslie would suddenly start picking Oona’s brain about the family, or that he’d criticize her baking—or that he’d somehow scandalize her just by being Leslie—but the two of them hit it off from word one. Leslie ate three hefty slices of her trademark key lime crumble, rolling his eyes in delight, and told her about his brand-new plan of working as a chef. He’d been kicked out of high school that morning, he explained, and an experience like that was liable to make a young man think about his future. Oona laughed what Kip liked to call her “dirty granny” laugh and lit another Camel. She was having the time of her life. Leslie asked if he could bum a smoke, and she winked and pushed the pack across the table.

Kip added that to his mental list of things that only Leslie Z could get away with.

There was no way he was going to let Leslie see his bedroom—with its NASCAR sheets, its Huey Lewis and the News poster, and its general air of defeat—so they hung out in the den, barely talking at all, watching reruns of Fat Albert and The Rockford Files. The house was a far cry from the Voglers’ expansive split-level, and Oona’s trashy Swiss chalet aesthetic made the rooms feel even smaller. It was like watching TV in-side a cuckoo clock. His grandmother sat with them for a while, making no attempt to conceal her satisfaction at seeing him with a flesh-and-blood companion, then returned to her mysterious old-lady business.

“That crumble,” Leslie said softly, watching her go.

“What about it?”

“It was awful.”

Things went quiet after that. Kip had never felt his shyness or his poorness more acutely. Leslie was still an enigma to him, a borderline-supernatural being, a visitor from the stars who spoke in riddles. Kip kept thinking that he was about to confess, to explain why he’d committed academic suicide that morning—but all that came out was the occasional half-grunted word. Watching reruns on Kip’s sofa was preferable, apparently, to digging a hole in his backyard and charging admission. But not by much.

“Leslie.”

“Present.”

“I guess I’m still wondering. About today at school.”

Leslie let out a yawn.

“Seriously, though. When will they let you come back, do you think?”

“I don’t.”

Kip hesitated. “You don’t what?”

“Care,” Leslie said, sticking out his tongue at the TV.

Finally, for want of any other option, Kip deployed the magic topic.

It worked instantly. Leslie picked up the conversation exactly where they’d paused it on the walk back from the Voglers’, as if he’d been waiting all week for the secret password. He became a completely different person when he was talking about metal. Kip understood him less but liked him better.

“Electric guitar is the greatest instrument in the world, Norvald—that’s been proven by science—and heavy metal is the music that proceeds from that reality. What else is there—piano? Synthesizer? Give me a fucking break. We’ve finally got the guitar where it belongs: up on the throne, on the altar, even higher than the singer. We’ve got electronics to shape the output now, to make the Word flesh, to boost the signal and to have it do our bidding. I’m talking about transistor-driven analog effects. I’m talking about the greatest musical instrument known to humanity put in the service of medieval knowledge: the infamous tri-tone, Norvald. The forbidden interval. The unholy trinity—diabolus in musica—not that I actually know what that means. Monks were burned alive for using it in their compositions—and that’s when they were playing it on lutes. But we’ve got the goods now. We’ve got the heavy artillery. We’ve got the electric guitar.”

“If you say so.”

“Look me in the eyes, Norvald. This is important. These lines have been converging for centuries—since the Dark Ages, basically—and they finally met in our lifetime. It’s just dumb luck that we’re alive to see it. It’s one in a billion. Are you listening to me?”

“I’m right here.”

“Sometimes I think about how easily I could have been born in a completely different era. I could have missed the eighties altogether. That unsettles me, Norvald. That gives me the chills.”

“I guess I never thought much about it,” Kip managed to get in. He was starting to wonder, in some dusty crawl space of his conscious mind, whether hanging out with Leslie might not be the best idea.

“It’s more than just a sound, of course. It’s more than an aesthetic. It’s the road less taken, Norvald. It’s the fucking left-hand path. It’s a complete shadow culture, with its own laws, its own myths, its own scripture. You could call it a whole Weltanschauung. If you were a Nazi.”

“Hold on, Leslie. You’re going a little too fast—”

“Take shredding, for example. Killer guitar licks are a fundamental feature of the heavy metal code. Unlike your standard punk riff—which can pretty much be played by a bonobo— this is music that demands OCD-level commitment. Think Yngwie Malmsteen, Norvald. Think Eddie Van. Think Randy Rhoads. These guys are basically neurotics. This is music that was technically impossible when our parents were our age. Guitars didn’t even have amplifiers when my father was a kid. Can you grok what that means?”

He went on like that for ages, from The Rockford Files to The Facts of Life to Remington Steele, and Kip sat back and watched him like a movie. Maybe the weight of what had happened that morning was catching up with him, or maybe he was as giddy with freedom as he claimed to be; whatever the reason, Leslie Z was in the grip of ecstasy. None of the inhibitions and anxieties Kip suffered from existed for him—at least not at the moment. He was high, obviously, but it wasn’t just that. He was operating on a conceptual level Kip could only dream of.

“I’ve had a gun to my head three times,” he was saying now, apropos of nothing. “One time it was Harley Boy. Twice it was the cops.”

“Three times?” Kip said, more than a little dubious. “What were you doing?”

Leslie sighed. “Get a clue, Norvald. I wasn’t doing shit.”

“I’m just saying, to pull that much heat—”

“Jesus Christ. Pull heat? Where did you hear that one, Starsky and Hutch?”

“People don’t get guns pointed at them by policemen for nothing, that’s all. Not in my experience.”

All at once Leslie looked brittle and tired. “We must have had differ-ent experiences with law enforcement,” he said. “I wonder why that is.”

“Come on, Z. You’re a rich kid. Or not rich, exactly, but definitely—” “You’re so hung up on the money thing. There’s worse problems, Norvald—at least around here. You think the good people of Venice see me walking down the street and stop to consider the Voglers’ fucking equity?”

Kip squinted at the TV for a while.

“Three separate times?” he said finally. “You’re not making this up?” “The last time was Thursday.” Leslie was cheerful again. “I’d been hanging at the Perkins out on the 41 bypass with Rozz—Chris ‘Flamer’ Rozz, you don’t know him yet—and he was driving me home in this car that he’s got. You’ve maybe seen it around school—he deals out of it sometimes. A brown Isuzu Gemini. You’ve smelled it, probably. He keeps it full of garbage. Keeps the po-po away.”

“I have smelled that car, now that you mention it.”

“So we’re rolling up the Tamiami with the windows cracked, listening to the new Amon demo—barely even flamed—when Greenwood pulls us over. You know Greenwood, right? Sheriff Greenwood? Usually he’s parked out by the mall.”

Kip shook his head.

“You ladies got any idea how fast you were going? Greenwood says to Rozz, shining this dinky little pen-flashlight into the back seat. He doesn’t say a word about the garbage. It’s possible he has no sense of smell.”

“Go on.”

“By this point Rozz is pretty much wetting the bed. He’s mumbling something about his speedometer being busted, about a family emergency, about having to go to the bathroom. Greenwood is just standing there grinning. Then he reaches in and opens the driver’s door, unbuckles Rozz’s seat belt, and says in the silkiest damn voice you’ve ever heard in your life: You were moving at an average speed of sixteen miles per hour. That’s when I knew we were roadkill.”

Kip was having his doubts again. “Wait. So he pulled you over for—”

“They don’t need a reason, Norvald. This place is the reason.” That shut him up again. Leslie yawned and slid a hand between the cushions of the couch. Eventually he came out with a quarter.

“That Amon tape is lethal, by the way. It caved my pointy head in.”

The Death show at the youth center was two days away.

__________________________________

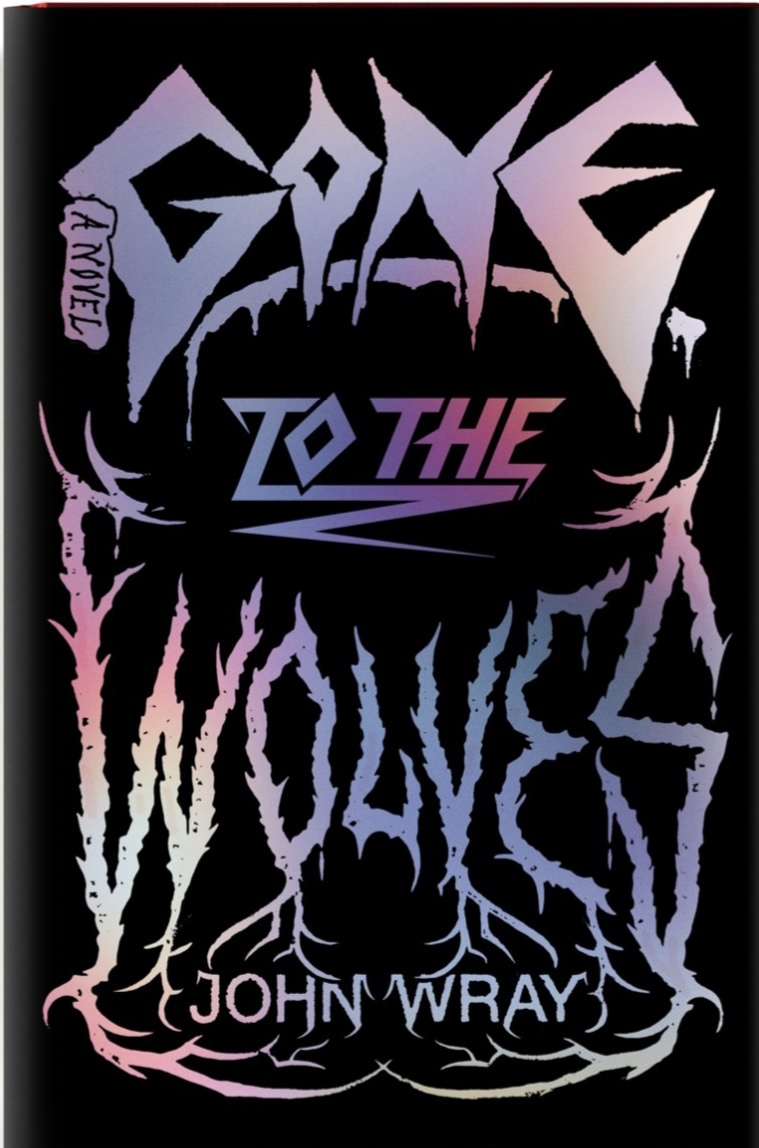

Excerpted from Gone to the Wolves: A Novel by John Wray. Published by Farrar, Straus and Giroux, May 2023. Copyright © 2023 John Wray. All rights reserved.