God-Tier Books: A Personal Library of Holy Scripture

Jon Raymond Recommends Don DeLillo, Denis Johnson, Theodor Adorno and More

One of the reasons you write a book is to talk about things you would never say out loud. Sometimes those are secret things, like bad feelings, or unpopular opinions, but more often they’re simply impressions too lyrical or banal for normal conversation. For instance, I’d almost never tell anyone how pretty I think a tree is—as if no one’s ever loved a tree!—but I’m constantly finding places to put heartfelt tree feelings into fiction. Same goes for things like making oatmeal or driving down I-5. Why describe it? But in a book you’re handing out phenomenological gossip, telling everyone how it feels to experience the world through your system.

I wrote a book called God and Sex (ridiculous title, I know) partly because those are topics my friends and I almost never discuss in real life. I mean, sex talk with gay male friends is fun, it’s true. It’s enviable. But among other friends of mine, barring something hilarious happening, we all generally keep what goes on when we’re naked to ourselves. And as for God, we never talk about that. My friends hold a healthy skepticism towards organized religion and spirituality in general. They see how quickly God talk veers into tedious, dorm room philosophizing.

And yet I love reading about God and sex both. In particular God. Over the years I’ve amassed a small shelf of books that I consider a kind of holy scripture for myself, a collection that produces in me a reliable sense of the numinous, or something akin—not so much the presence of the divine as the recent presence, the still-warm absence. These are books that, to me, suggest mysteries beyond comprehension, and distant, unapproachable majesty. They are durable engines of amazement and humble gratitude.

*

Pseudo Dionysius the Areopagite, Collected Writings

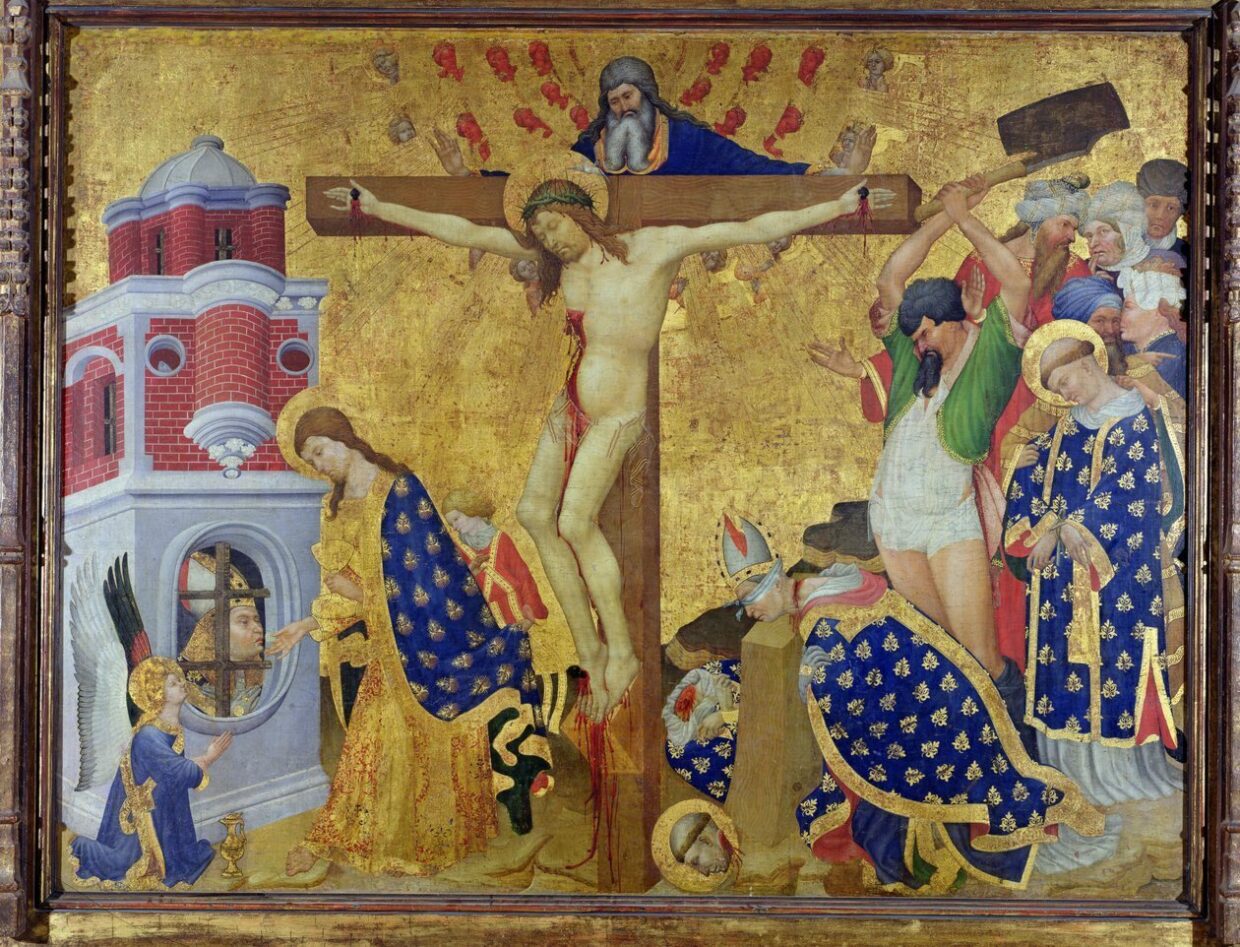

I first discovered these writings in college while writing an art history thesis about a French altar piece from 1416 called retable de Saint Denis. It originally hung in a Carthusian monastery where monks silently contemplated it from separated cubbies, almost as in a panopticon. The panel depicts two moments in the life of St. Denis—his final communion in prison and his martyrdom by beheading—unfolding underneath a gaudy crucifixion beaming with seraphim. It’s a busy picture, crammed with disparate times and places, shaped by Medieval notions of divinity and representation that lead back to a certain, anonymous Neoplatonist from the fifth or sixth century in Greece named Pseudo Dionysius the Areopogite.

In fragmentary writings with titles like “The Divine Names” and “The Celestial Hierarchy,” Pseudo Dionysius laid out some of the early concepts of what people have come to call the apophatic tradition, or negative theology—a way of seeing that believes the best approach to thinking about the divine is through negation rather than affirmation. As no image or word can ever approach the reality of the divine Godhead, or what Pseudo Dionysius calls the “Superunknowable,” the best we can do is describe what it is not. And in this failure, possibly stoke a better appreciation of the ever-hidden object of wonder.

As a college kid, this was all extremely exciting to me. Ancient writings by a pseudonymous mystic! Medieval monks arguing about the nature of light! A gnostic theology based on extreme negativity! The negative path, I could see it. Has this led me to fetishize my own ignorance over the years? Possibly.

Meister Eckhardt, The Complete Sermons

Meister Eckhardt was a German Catholic monk in the 11th century influenced by Pseudo-Dionysius. His writings were condemned by the church as heresy but found a fan centuries later in Martin Heidegger, which makes sense. Eckhardt’s commentaries on God and scripture are dense and recursive, breaking ideas into component parts, placing them onto higher and lower planes, making hierarchies and triads out of them until eventually becoming something like an investigation into being and nothingness themselves. Occasional gnomic jewels emerge from the tangle: “God is a word, a word unspoken.” “God is a word that speaks itself.” The mobius-thinking at times almost seems like Medieval Zen, what with the emphasis on emptiness and silent meditation, and in fact that was what the Church fathers objected to most: too much quiet, solitary contemplation, not enough pious instruction.

This collection of anonymous writings from 14th-century England is yet another text inspired by Pseudo-Dionysius. This one is simpler than Eckhardt, though, more like a guidebook in the style of contemporary mindfulness manuals. Hold a key word in your head, like “love” or “God.” Don’t worry too much about intruding thoughts, just let them come and go. Avoid thoughts of people you revile. Mostly, enter the “cloud of unknowing” (after passing through the “cloud of forgetting”) and focus on the notion of God as the maker and giver of time, the smallest particle of which is referred to, interestingly, as the atom.

Franz Kafka, Collected Stories

When I was a teenager, Kafka arrived cloaked in all the vestments of High Modernism. He was a very serious Existentialist author, angst-ridden and paranoid, who inhabited a world of severe black and white photography. Only later did I come to see how funny, charismatic, hapless, and romantic he was. And cosmic, too. Kafka is the master of bringing immoveable objects into contact with unstoppable forces and building traps that fit only one person or animal in creation. His thought experiments lead sometimes to stone walls and sometimes to flashes of insight or hilarity, always with an un-erasable Jewish inflection. For this batch of sentences alone (which harmonizes nicely with the Christian authors above), I thank him in perpetuity: “You do not need to leave your room. Remain sitting at your table and listen. Do not even listen, simply wait, be quiet, still and solitary. The world will freely offer itself to you to be unmasked, it has no choice, it will roll in ecstasy at your feet.”

Howard Schwartz, Gabriel’s Palace

This is a great book in part because it helps illuminate the roots of Kafka’s imagination. In Howard Schwartz’s version of Rabbinic folktales, the images and storylines of Jewish folklore become colorful, polymorphic, and wondrous while never losing an aura of ancient scariness. It’s like Jewish magical realism; as strange and phantasmagoric as any indigenous myth tradition.

Don DeLillo, The Names

They say Joan Didion read Joseph Conrad’s Victory before beginning every novel she wrote. I do that sometimes with The Names. There is a certain frequency DeLillo captures, or maybe creates, not entirely unlike that of Conrad’s and Didion’s in its clairvoyance and occasional portentousness, that suggests a secret world hovering behind the world of the everyday. It’s a place of cryptic patterns, distant, unknown powers, and wicked forces at work, never so much revealed as insinuated. In The Names, DeLillo installs his radar in the figure of James Axton, a recent divorcee and risk assessment analyst who follows his ex-wife and young son to Greece. His filmmaker friend Frank Volterra shows up, seeking a rumored cult responsible for ritual murders based on alphabetical motives.

The book progresses as a mystery, of sorts, but more like a meditation on language and violence, modernity and antiquity, terror and sex, revealing contemporary life (a contemporaneity that is still our own) as a series of onrushing glyphs from the past and the present bearing important religious and political meanings that sadly (Satanically?) can never be fully decoded. The opening moments at the Parthenon always hit me like a gong: “What ambiguity there is in exalted things. We despise them a little.”

Denis Johnson, Angels

Denis Johnson is not part of any apophatic tradition. He’s more in the line of cracker eschatologists like Flannery O’Connor and Cormac McCarthy, writers not so interested in silent contemplation as angels and demons and hearts on fire. In Johnson’s first novel, Angels, we’re invited to hang out with a collection of desperate characters as they tack through an American demimonde of crime and drugs, brushing often against the shimmering, thin veil between worlds. Irrational violence and lyric visions erupt in lacerating, supremely elegant prose that’s also genuinely funny at times. Dare I say, revealed? I might as well just make a confession here: Denis Johnson is probably my favorite American writer, which isn’t much of a confession, I guess, considering my age and demographic, but still… Also, I confess that I stole a major image from Angels in a book I wrote, the figure of an angel as intergalactic Gestapo agent. I found it so thrilling I had to use it. As long as I’m at it, I’ll go ahead and confess this, too: I also stole the surname of Frank Volterra from The Names for a different book. I hope my trespasses can be forgiven.

Theodor Adorno, Minima Moralia

What if instead of the Torah your rabbi read Das Kapital? That’s how I think of Adorno, the most mystical of historical materialists. Minima Moralia, composed in the shadow of the Holocaust, collects quasi-Marxian fragments and aphorisms that even as postscript to atrocity read as terrible prophecy. By Adorno’s thinking, fascism was never defeated. Rather, it entered into the very fibers of Western mass culture, if not human consciousness itself, and remains detectable in trace amounts in pretty much every thought and action imaginable. Drinking whiskey. Watching movies. Putting on your shoes. In bitter truisms for the ages—“German words of foreign derivation are the Jews of language.’; “A German is someone who cannot tell a lie without believing it himself.”; “The whole is the false.”—Adorno ransacks his mind for any semblance of hope, but finds none. One has to wonder what he’d have made of the world today, and the historical mutations that have led us to a place where “Zionist fascism” and “Zionist genocide” make tragic sense. Even Adorno might have been stupefied.

Charles Portis, Masters of Atlantis

My dad was a California Buddhist with Sufist leanings. His gurus through the years ranged from Krishnamurti, to Ram Dass and D.T.. Suzuki, to George Gurdjieff and Gurdjieff’s interlocutor, P. D. Ouspenski. He read the Urantia Book (an elaborate, possibly nonsensical New Age cult tome) with a towel on his head to keep the thoughts from floating away.

All of which might explain my immense affection for Masters of Atlantis, Charles Portis’ 1985 novel of the rise and fall of a homegrown American religion called Gnomonism. Less Mormonism or Scientology than Free-Masonry or the Knights of Templar, Gnomonism is a flimsy fraternal order based on Americanized bastardizations of Medieval-ish theology. There are lots of triangles involved, numerous lost source texts, much esoterica for its own sake. As one adherent thinks: “The Rosicrucians had finer robes and the Brothers of Luxor had eerier ceremonies, but in the way of ideas that could not quite be grasped, neither of them had anything to touch the Cone of Fate or the Jimmerson Spiral.”

The Jimmerson Spiral is named after Mr. Jimmerson, the leader of Gnomonism’s North American wing. He’s a dreamy, bumbling figure, cut from the cloth of American inventors and hobbyists throughout the ages—men with giant balls of twine in their garages, experimental flying machines in their back yards, interstellar radio receivers in their tool sheds. Can you imagine that now? An American innocent.

__________________________________

God and Sex by Jon Raymond is available from Simon & Schuster.

Jon Raymond

Jon Raymond is the author of five works of fiction, including the Oregon Book Award–winning story collection Livability and the Oregon Book Award–nominated novel Denial. As a screenwriter, he has collaborated on numerous films with the director Kelly Reichardt, including Old Joy, Wendy and Lucy, and First Cow. He also received an Emmy Award nomination for his screenwriting on the HBO miniseries Mildred Pierce directed by Todd Haynes and starring Kate Winslet. He was the editor of Plazm Magazine, associate and contributing editor at Tin House magazine, and a member of the Board of Directors at Literary Arts. His writing has appeared in Zoetrope, Playboy, Tin House, The Village Voice, Artforum, Bookforum, and many other places. He lives in Portland, Oregon.