Nobody in Ichulu cared for the erosion. Its tired old and its tired young were rebuilding the village indifferently. Its little ones were keeping weary smiles and discarding playtime, giving skinny dogs their place in the orange mud. Its surviving cassava leaves were drinking their share of light, with folded, wrinkled chaff corrupting the cassava’s green. All in Ichulu, every person, every household, ignored the honored eagles soaring over them.

Igbokwe foretold the dangers this rainy season would bring, scurrying behind forest trees, booming his quivering cries. He pronounced them many weeks before the storm, several weeks before it came, and was not moved to read his cowrie shells the morning the message arrived. White paint adorning his old, small body bequeathed him with gifts like clairvoyance—as the gods themselves revealed a message in the skies once a cock had crowed its fourth crow. And when he emerged from his red-painted obi, with equanimity beside him, praying a small prayer and then trudging toward a goat-horn cup for water, his gaze met the clouds, clouds shaped in ominous ways—clouds shaped in symbols that he could not name, lurking within the sickly firmament of Igwe, the god of the sky. His eyes filled with panic. He opened the earth with the tip of his staff. Its bells were shaking with war on their lips. He could not wait for the town crier, his words were too urgent, he had to deliver it himself, every ear in Ichulu was to hear his solemn warning—

“It is coming! It is coming! Dangerous water is coming!”

The fear and confusion that followed traveled faster than the winds of harmattan. Nobody in Ichulu could say how water could harm. The town stretched along Idemili, a sacred river that gave the people a place to bathe, to drink, and to witness their faith in the god after whom the river was named—Idemili, the one for whom the river was. To touch the waters of the river was to touch the body of the divine. Irrigation channels ran from the riverbanks to the rippled farmlands: heaps of earth impregnated with the seeds of yam, groundnut, and other vegetation. The village did not thirst. The children did not drown. Idemili lived for Ichulu, and Ichulu satisfied him. It held past storms with ease given Igbokwe’s divinations. If a storm’s language became threatening, Igbokwe subdued Idemili with a sacrifice. Now, Igbokwe, consulter to the gods, warned that this long-sacred deity was to attack.

This wild pronouncement might have caused the village to ignore Igbokwe’s cries echoing from within the forest. But the people of Ichulu knew Igbokwe’s word to be good and believed him to be a matchless diviner. He possessed power known far past the ends of Idemili, which the white ones too had come to fear. On days filled with jeering and humor, the elders would remind the little ones of when the white ones lost their way, stumbling upon the village seeking to establish the laws of a foreign god—laws that would shatter the peace of Ichulu as well as the peace of the white ones and their village. They would say that the white ones first came with friendship woven into their smiles, promising to build schools for the children’s reconnaissance and to build a church where the white ones spoke often of their god. Then, after four Eke market days, their friendship turned to enmity and their smiles converted to bullets. It was said that the power of Igbokwe’s predecessor caused those inept schools to crumble, and caused the barren church to collapse. It was said that the power given to him by Ichulu’s gods expelled the white ones from the village as they cried, “Their midget witch doctor has deranged me! Give me anything, anything to drink!”

“But what is witch, ehhhh?” the elders would say, chortling above the little ones. “Igbokwe—that shorter man you see—he is our dịbịa.”

Ichulu remembered the wars fought by the town of Etuọdị, and it remembered the negotiations initiated by the town of Ụmụka. It remembered, because neither the sword nor the tongue prevented either town from being toppled by the poison of a white god. “Where were the gods of Etuọdị and Ụmụka,” Ichulu’s people would ask as they threw snaps of disdain, recounting how men were imprisoned for speaking to the ones called their ancestors; and how schoolchildren were mercilessly beaten for uttering the sounds they were taught to speak; and how the fate of Anị, the goddess of the earth, was sung of in dirge, as hidden voices seldom remained to pass on sacred memories.

Only the village of Ichulu remained as it was. It remained because of the divination of Igbokwe and his predecessors—divination that came through the one called their god. Chukwu was the life source of the line of dịbịas. While it was true that their homage to Anị, Ikenga, Amadiọha, and the rest of the gods seldom wavered, they knew that the entire pantheon summed to nothing without the Supreme Being. Chukwu was the most of what any thing or one could be—the greatest among that which could be called great. Chukwu was called Chineke when Chukwu made creation; Chukwu was called chi when Chukwu became a friend; Chukwu was everywhere, unbound to any material thing. Anị had her earth; Anyanwụ had his sun; Igwe had his sky; Idemili had his river. But Chukwu-Chineke-chi governed all creation. Even as the dịbịas worshipped Idemili, Chukwu was the one they had, the one who empowered them to guide and protect the village.

So when the present Igbokwe cried that dangerous water was coming, the people of Ichulu jounced in an unexpected fear. Men hurried to thatch the roofs of their compounds with the town’s thickest palm leaves, nimbly weaving the leaves in the patterns of nests, and praying that Igwe, the god of the sky and the bearer of rain, would send them time. Women rushed to the market to sell a portion of their premature harvest, with a woman named Ngọzi already selling forty cups of groundnut, causing the others to wonder how a woman who could not conceive, how it was that she could quickly harvest and sell such an abundance of produce.

The animals, too, prepared themselves. The black nza birds flocked away from the town, dismantling their cushioned nests and migrating toward Ụmụka in the north. The vultures left the festering carcasses and sojourned northward as well, as the cows, cocks, goats, and rams allowed themselves to be sealed in barns by their owners and peacefully waited for the storm to come and pass. And the little ones, they felt no anxiety at Igbokwe’s words, but grew eager in taking a thousand showers beneath the clouds—to feel the touch of raindrops—knocking, knocking—against their naked skin.

But on the day after Igbokwe’s pronouncement, the elders of Ichulu gathered to discuss their plans to avert the storm. They knew they were required to offer something to Idemili, and they purchased a bull to appease the god of the river. Soon, they beheld four very young men pressing the animal down with taut bodies as Igbokwe opened the bull’s neck with a blade, collecting its spilling blood with a metal bowl while praying over it and asking Idemili to protect the people of Ichulu. He reminded the deity that if he failed to send mercy to the village, the people would condemn him, and he would be chastised by the power of Chukwu—warning that the Supreme Being would send a new river, and the people of Ichulu would find a new god. He reasoned. He asked. He threatened. Still, when the elders looked to Igbokwe’s face for signs that the sacrifice was taken, they wondrously found an empty gaze: abandonment and apathy.

Igbokwe was befuddled. He did not understand what could cause the storm, since he had placed four holy stones from the depths of Idemili in the four corners of Ichulu. The stones were feared throughout the village, as they had been among the stones living beneath Idemili, which kept the river clear and unpolluted. Nobody would dare move them, he believed, while thinking of the one he placed in the northwest corner, in the forest used for hunting; then thinking of the one he placed in the southwest, near Idemili, where compounds sat beside one another; then thinking of the third, placed by the iroko trees in the southeast, which separated Ichulu from Amalike; then the last one—the one he saw in his mind—lodged deep inside the northeast, fixed within the Evil Forest. He had blessed them each morning, and could not understand why they now failed, and dismissed the thoughts of accusing a faultless person, or an innocent town. And before Anyanwụ, the god of the sun, had departed from the day of sacrifice, Igbokwe knelt among his scattered cowrie shells cast within his obi, offering supplications to Chukwu, pleading to the Most Supreme that power be restored to those holy stones.

“Who? Who? Who would curse us this way?” implored the women selling food near sunrise.

“It could be those goats from the village of Etuọdị,” one said as she adjusted her mat of greens.

“Sit down!” said another, while biting on her chewing stick. “Whose gods are greater than the gods of Ichulu? Or are you among the foolish—those stupid ones—who have forgotten the power of Idemili?”

“Then you have not heard of emissaries going to Amalike to remove the curse from Ọfọdile’s child?”

Ngọzi, a childless woman, was pouring groundnut onto her light yellow cloth as she spoke good words to the others.

“Ijeọma? The mute? But for what?” said the woman with the chewing stick.

“Yes. Ijeọma,” Ngọzi said, “It is a good word. My husband told me that after the sacrifice failed, Igbokwe spoke with the gods, and they told him that whoever cursed Ọfọdile’s daughter also cursed the people of Ichulu with this evil water that is coming.”

Ngọzi heard the women laughing, and saw them turn their heads from her—knowing that it was because she had not given birth to a living child.

But she continued pouring her groundnut, and disregarded their eschewals, leaving the market women to themselves.

_______________________________________

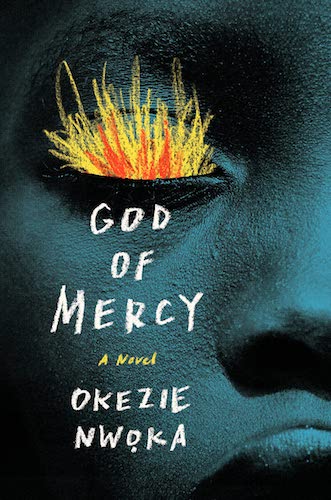

Excerpt used by permission from God of Mercy (Astra House, 2021). Copyright © 2021 by Okezie Nwoka.