Goatskin, Tree Bark, and One Expensive Scribe: How “The King of the World’s Booksellers” Produced Manuscripts

Ross King on the Laborious Process of Bookmaking in the 15th Century

Producing new manuscripts of Cicero’s writings in the middle of the 15th century was clearly a more laborious and involved enterprise than combing the sleepy shelves of Franciscan libraries for neglected codices. The word “manuscript” comes from the Latin manu scriptus, “written by hand,” but any manuscript was the product of much more work than simply the writing of a single hand. It was a months-or even years-long, multistep process calling for the expertise of a series of tradesmen and specialist craftsmen, from parchment makers to scribes, miniaturists, goldbeaters, and even apothecaries, carpenters, and blacksmiths.

The essential first step was finding the exemplar: the text, as reliable as possible, from which the scribe would work. It is no coincidence that on his excursion to Lucca in 1445 Vespasiano da Bisticci—known at the height of the Renaissance in Florence as “the king of the world’s booksellers”—purchased two copies of Cicero from Michele Guinigi. His sharp eyes no doubt spotted that these manuscripts would be excellent texts to compare with those volumes he was preparing for Grey.

Vespasiano occasionally produced works on paper, of which, like all cartolai, he carried ready supplies. For the most part, though, his clients expected him to use parchment. Cartolai carried stocks of parchment, which was made from the skin of sheep or goats, and sometimes also from donkeys. The most beautiful and expensive material on which to write was calfskin, or vellum, the word “vellum” coming (like the word “veal”) from vitulus, Latin for “calf” (vitello in Italian). The younger the calf, the finer and whiter the skin; uterine vellum, from aborted or stillborn calves, was the finest and whitest of all—but also, because of its rarity, infrequently used.

The supply of hides for parchment was always dependent on the dietary preferences of the local population. The appetite in Italy for goats (one recipe book offered advice on how to spit-roast, boil, or stew them, how to cook their eyes, ears, lungs, and testicles, and how to make pies from their heads) meant that manuscripts in Italy were often made from goatskin. This reliance of the book industry on the palate of the locals is reflected in the lament by a 13th-century Patriarch of Cyprus, Gregory II, that not until after Lent, when people began eating meat again, would he be able to get the hides required for a manuscript of Demosthenes. For hundreds of years, the transmission of knowledge had depended on carnivorous appetites and good animal husbandry. Large volumes with hundreds of pages required the skins of many animals. One goat was often needed for each page of parchment in a large liturgical book such as an antiphonary, while a Bible might take the skins of more than two hundred animals—an entire herd of goats or flock of sheep.

Parchment makers in Florence were, like the cartolai, clustered around the Badia in the Street of Booksellers. To purchase their hides they needed to visit the butchers on the Ponte Vecchio. In 1422, for reasons of hygiene, the government ordered the city’s butchers to move their operations into the shops on the bridge, already occupied by tanners, fish sellers, and beltmakers. From here the butchers could happily pour blood and other slops straight into the Arno, rather than, as before, befouling the city’s streets. The parchment makers, in competition with the tanners, would try to get the best hides from the butchers, those with the fewest nicks, cuts, and scars, and the least number of bites from ticks and flies.

The process of making parchment was scarcely less foul-smelling than the work of the tanners, who used both urine and dung to cure their hides. The parchment makers would cart their heap of skins back to their premises, smear them with a corrosive quicklime, fold them lengthwise, then put them into a vat to ferment. After a week or two, the hides would be fished from the vat, bathed in limewater, and then attached with pegs to wooden frames and stretched tight as the remaining hair and flesh was scraped away with a crescent-shaped knife. Still taut on the frame, they would be rubbed with chalk or bone dust and scrubbed with a pumice stone, or perhaps the bone of a cuttlefish. Then they were rubbed and scrubbed again and again, until the surface of both sides was smooth and pale, though sheepskin always yielded a yellowish cast and goatskin a slightly gray one. The skin was then cut from the frame in a neat rectangle.

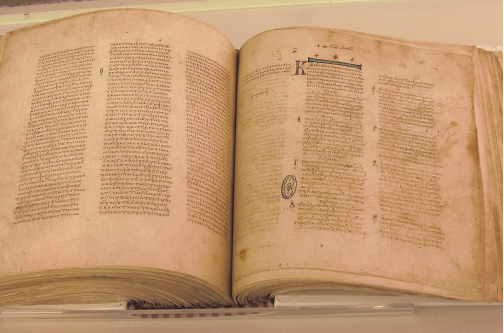

The parchment codex, made from animal skins, began supplanting papyrus scrolls as the most prevalent support for writing by the fourth century AD. This new format, adopted by Christians, was more durable and could hold a greater amount of information. Photographed by Leszek Jańczuk, via Wikimedia Commons.

The parchment codex, made from animal skins, began supplanting papyrus scrolls as the most prevalent support for writing by the fourth century AD. This new format, adopted by Christians, was more durable and could hold a greater amount of information. Photographed by Leszek Jańczuk, via Wikimedia Commons.

The rectangular shape of books (through the Middle Ages codices generally had a width-to-height ratio of 2:3) was in many respects determined by the shape of the animal skins once they had been trimmed of their extremities. These outer scraps served to make glues, while other offcuts, such as the skin from the shoulders, neck, and flanks, with their coarser grain and more awkward shape, might be used as cheap parchment for children’s books such as the Santacroce.

The next operation involved paring away the skin with another sharp tool, reducing it to roughly half of its original thickness. The parchment maker had to be careful neither to tear the skin nor to create an uneven thickness. Parchment for large, luxurious manuscripts was scraped less so it remained robust enough to carry the decorations. Even so, these pages were reduced to a thickness of 0.1 millimeter, or 1⁄250 of an inch. At this point any flaws in the skin, from the bites of insects or the gashes of old wounds, could leave the surface with small oval perforations around which the scribe would have to work. The defective quality of the parchment—if it was too rough, greasy, or brittle—was one of the many things about which scribes complained in their manuscripts. “The parchment is hairy,” griped one medieval scribe.

The large rectangle of parchment was then cut into four or eight pieces. Parchment was sold in various sizes according to the type of book for which it was destined. One of the largest sizes was used for antiphonaries, which needed to be read simultaneously from a distance by many pairs of eyes—those of choir members. Their pages were often two feet high by more than a foot wide, with the staves (the horizontal lines on which the musical notes appear) drawn almost two inches high. The pages of parchment used by Vespasiano for his edition of Cicero for William Grey were fourteen inches high by ten inches wide, the size known as foglio comune, or common sheet.

Parchment in Florence was usually sold in quires made up of five sheets folded in half to make ten leaves, which, inscribed on both sides, gave twenty pages of text. One of these quires of foglio commune could cost as much as ten soldi. Given that his manuscript of Cicero’s rhetorical writings required 125 leaves, or more than a dozen quires, the parchment for this volume alone must have cost Vespasiano roughly one and a half florins. This sum was a significant outlay—roughly a month’s rent on the shop in the Street of Booksellers.

And the most expensive labor and materials were yet to come.

Having supplied himself with parchment, Vespasiano was ready to hire a scribe. Monks in the Badia, across from Vespasiano’s shop, still worked as scribes. So too did the Franciscan nuns at the convent of Santa Brigida del Paradiso, the Benedictine nuns in Santissima Annunziata della Murate, and indeed the nuns at some five other convents scattered in and around Florence. However, the manuscripts they produced were liturgical in nature—breviaries, lectionaries, missals, and so forth. In Florence, as in much of the rest of Europe, the scribes who copied secular works such as the Latin classics were not found in the scriptoria of abbeys and convents but rather in the shops of notaries and the studies of assorted scholars who might otherwise work as secretaries to wealthy men or tutors to their sons. Notaries made ideal scribes because their profession called on them to prepare contracts and other documents in Latin, on parchment, in a legible handwriting. There was no shortage of them either, because notaries were the most numerous profession in Florence in the first half of the 15th century—and many of their shops lined the Street of Booksellers and Via del Palagio.

Most of the scribes employed over the years by Vespasiano, such as Ser Antonio di Mario, were indeed notaries (all of whom used the honorific “ser,” rather as “Esq.” is added after a lawyer’s name). Many notaries topped up their incomes by copying manuscripts part-time in their shops or homes, but others, such as Ser Antonio, abandoned the notarial profession altogether and worked full-time as scribes, often quite lucratively. Indeed, the scribe represented a bookseller’s greatest expense, taking up as much as two-thirds of a manuscript’s production cost, at least twice as much as the parchment. They were generally paid by the quire, earning a fixed sum for every ten leaves of parchment, or twenty pages copied front and back. The average fee was around thirty or forty soldi per quire, at which rate Ser Antonio would have been paid more than five florins for his work on the Cicero manuscript for William Grey. Copying ten or twelve such manuscripts per year would allow a scribe to bask in more than tolerable comfort.

Scribes often needed to work quickly and prolifically due to the demands of the patron, the time limit imposed by whoever lent the exemplar, and their own financial needs. One of the most impressive scribal feats in Florence was that of a copyist in the middle of the 1300s who produced—over the course of some twenty years—what became known to legend as the gruppo del Cento, or “the Group of One Hundred”: one hundred manuscripts of Dante’s Divine Comedy, the proceeds of which provided dowries for the scribe’s numerous daughters.

The offspring of his daughters’ marriages called themselves dei Centi, “of the Hundred,” proudly taking their surname from the pen-pushing efforts of their grandfather.

Many other remarkable scribal feats are on record. One copyist working in Florence managed to complete a quire (that is, twenty pages front and back) every two days. Poggio worked at double that speed when he produced his complete Quintilian in thirty-two days, turning out a quire each day. He once copied out 152 pages of a work in twelve days, and in 1425 he promised to provide Niccolò Niccoli with a new manuscript of Lucretius’s On the Nature of Things in only two weeks, although in the end the job took a month. One of the quickest quills belonged to a scribe named Giovanmarco Cinico, who once copied 1,270 pages of Pliny’s Natural History in 120 days, and in a beautiful and legible hand. He signed himself, appropriately enough, as Velex—“Speedy.”

We have no record of how long Ser Antonio took to copy the 250 pages of the manuscript for William Grey. But he generally worked both swiftly and prolifically. He completed a manuscript of Virgil in April 1445, only seven months before signing the Cicero for Vespasiano. In the previous twelve months he had copied out two manuscripts of Leonardo Bruni’s History of Florence, a massive tome that stretched to 300 leaves of parchment, or 600 pages.* In one year he managed to copy at least seven manuscripts, including one of Bruni’s translations of a Platonic dialogue.

An illuminated letter Q in one of the Cicero manuscripts prepared by Vespasiano for William Grey. The design features an ultramarine blue background with gold leaf and the elegant, encircling tendrils of white vine-stem decoration. Balliol 248C, folio 12r. Courtesy of Balliol College, Oxford University.

An illuminated letter Q in one of the Cicero manuscripts prepared by Vespasiano for William Grey. The design features an ultramarine blue background with gold leaf and the elegant, encircling tendrils of white vine-stem decoration. Balliol 248C, folio 12r. Courtesy of Balliol College, Oxford University.

In selecting Ser Antonio, Vespasiano had wisely chosen for this important early commission a talented and capable veteran with almost thirty years of experience. His beautiful handwriting graced the manuscripts of many important and cherished works: Gellius’s Attic Nights, Plutarch’s Lives, Varro’s On the Latin Language, Bruni’s translations of both Plato and Aristotle, along with many others. He copied manuscripts for the finest collections in Florence. He was, in fact, Cosimo de’ Medici’s favorite scribe, including at the end of his transcriptions affectionate salutations such as “Happy reading, sweetest Cosimo.”

Such comments Ser Antonio always placed at the end, in what has come to be known as the colophon. The word “colophon” derives from the Greek κορυφή, meaning hilltop or summit, but at some point it took on a metaphorical sense of a finishing touch or crowing stroke: ancient Greek philosophers spoke of “putting a colophon” on an argument.

We can appreciate how a scribe, having copied hundreds of pages of a manuscript, may well have felt he had scaled a summit, and the term was adopted for the designs, flourishes, and slogans often added by scribes to the ends of their manuscripts. The scribe who copied part of Aquinas’s massive Summa Theologica ended with a cry of exhausted triumph: “Here ends the second part of the work of Brother Thomas Aquinas of the Dominican Order, incredibly long, verbose and tedious for the scribe. Thank God, thank God, and again thank God!”

At other times scribes addressed future readers, cautioning them to be careful with the manuscript: “I beseech you, my friend, when you are reading my book, to keep your hands behind your back, for fear you should do mischief to the text by some sudden movement.” Scribes often asked readers to pray for their souls. A humorous variation on this convention appeared in a manuscript copied by a Florentine nun named Sara. “Let whoever reads this devout life pray God for me, poor Sister Sara,” she began, before adding, “And if you don’t I’ll strangle you when I’m dead.”

For his colophons, Ser Antonio used a compass to draw a circle around whose 360 degrees he would put his name and the date, sometimes also recording an ongoing event. He began his long career in the summer of 1417, when he ended a manuscript with the observation that he had been “laboring during the plague in Tuscany.” One of his other manuscripts, signed in May 1426, states that Florence was bravely fighting the “tyranny of the duke of Milan, who was waging an unlawful and unjust war.”

Vespasiano prepared the parchment for Ser Antonio by ruling it with lines, both horizontally and, to justify the text, vertically at the margins. This task would have been among the first he learned from Michele Guarducci. Cartolai pricked the margins with a needle or a pinwheel, often pushing the point through as much as a quire at a time. The operation required a certain amount of physical strength (and no doubt sometimes resulted in minor injuries). The small perforations indicated where exactly the horizontal lines should be drawn or, less often, scored with a stylus.

The point of pricking a quire at a time was to make sure the spacing was uniform on all of the pages. Ser Antonio’s Cicero manuscript features 36 lines of text on each page, with the guidelines in pale ink still faintly visible. The job of ruling the parchment was a tediously repetitive one, but it had the obvious importance of ensuring evenly spaced lines and a text that ran undeviatingly across the pages. As in Florentine architecture, so in Florentine manuscripts, beauty lay in simplicity, regularity, and symmetry.

With his parchment awaiting him, Ser Antonio takes a seat at his desk. His writing surface, sloped at an angle of around thirty degrees, holds the exemplar, the blank quire, and two inkhorns fitted into holes. To remove any grease from the page, he sprinkles it with chalk or bone dust, the latter made (as one manual advised) by incinerating the leg or shoulder of a sheep and then grinding the ashes on a porphyry slab. Then, to remove the excess dust, he brushes the surface with a hare’s foot.

Next comes the preparation of the vital instrument of his labors: his quill, made from one of the flight feathers of a goose (the word pen derives from the Latin penna, “feather”). He has already carefully trimmed the barbs from the shaft, which is seasoned to the right hardness, but still supple. He cuts its tip to a point and then, to make the nib more pliable and help the flow of ink, makes a short incision along its length. These procedures he will repeat numerous times a day, his quill slowly growing shorter as he pares it away.

As in Florentine architecture, so in Florentine manuscripts, beauty lay in simplicity, regularity, and symmetry.Next Ser Antonio dips the quill into one of the two inkhorns. One holds black ink, the other red. The main ingredients for the former are wine and the barks and saps from various trees, including oak galls, the small, tannin-rich lumps that grow on the twigs of oak trees where gallflies lay their eggs. One Italian recipe for black ink advised taking four ounces of crushed galls and mixing them with a bottle of strong white wine, pomegranate rinds, bark from a mountain ash, the root of a walnut tree, and gum arabic—the sap from an acacia tree.

These ingredients were left in the sun and stirred every few hours. Into this concoction were added, after a week, a few ounces of “Roman vitriol,” or copper sulphate. The mixture then sat a few days longer and was regularly stirred. Then it was placed over the fire and boiled “for the space of one miserere ”—as long as it took to recite the nineteen verses of Psalm 51. Next the bubbling black liquor was cooled, strained through linen, and left to sit in the sun for two more days. “If you then put in it a little rock alum it will make it much brighter,” the recipe claimed, “and it will be good and perfect writing ink.”

Ser Antonio bought his supply of black ink from either a cartolaio (who also sold goosequill pens) or one of Florence’s monasteries. On a scrap of paper or parchment, making a short doodle, he tests out both the nib and his red ink. He can make red ink himself by mixing egg white and gum arabic with cinnabar, a reddish stone found in Tuscany and purchased, already ground, from the local apothecary. Another dip in the inkhorn and he hovers over the blank page, its buoyant surface pressed down with the knife he holds in his left hand. His middle finger is farther down the shaft than his index: the better to control the nib. He holds his quill at a right angle to the surface of the parchment: the better for the ink to flow from nib to page.

After a quick check of the exemplar, Ser Antonio brings the nib down to the surface—he is writing on the smoother, flesh side—and makes his first stroke. Three short movements, three quick changes of angle and pressure. Without lifting the pen he makes a swift feint to the right, a slower and heavier downward stroke, then a slight release of pressure and another feathery, horizontal feint before the nib is lifted clear: the letter I, its downstroke topped and tailed by tiny serifs.

Ser Antonio continues in block capitals, still in red: IN HOC CODICE CONTINENTUR. “This book contains . . .” He is pronouncing the words aloud as he writes, the better to remember them as his eyes move back and forth from the copy text to his parchment. “Three fingers hold the pen,” wrote one scribe, “two eyes see the words, one tongue speaks them, and the whole body labors.”

Ser Antonio works his way down the page, providing the table of contents in red ink. It is a roll call of some of Cicero’s most famous and influential works, such as Letters to Atticus, rediscovered by Petrarch in Verona in 1345, and the Orator and Brutus, both rediscovered more recently in Lodi. Vespasiano probably acquired the exemplars for Ser Antonio from Cosimo de’ Medici, who had copies made for himself in the 1420s. He may also have found them in the library of San Marco, for in 1423 Niccoli copied out both the Orator and Brutus in his distinctive script.

Ser Antonio completes the contents page and moves on to the next. The quire has been arranged by Vespasiano such that this facing page, the first of the text proper, is also the smoother, flesh side. Flesh sides always face flesh; hair sides always face hair (these are slightly rougher, often lightly stippled from the follicles). Ser Antonio trims a new quill, this time cutting a finer point, then dips the nib into the black ink. After another pen trial he begins writing. The first text is the Rhetorica ad Herennium, in which Cicero gives his friend Gaius Herennius lessons on how to make a speech. It was a treatise much loved by the humanists in Florence, where a successful speech depended on the ability to use logic and reason to persuade others, to “bend your auditor to go wherever you might want.”

Ser Antonio begins copying out Cicero’s words, not in block capitals but in a smaller hand, an elegant, legible script of which he is one of the earliest and most talented pioneers. This so-called humanist script is a gift that the scribes of Florence bequeathed to the world, one no less important than the rediscovery of the works of Cicero or Quintilian, or the perspective grids of Brunelleschi and paintings of Masaccio—a gift that the manuscript expert Albert Derolez has called “one of the great creations of the human mind.”

*After his death in 1444, Bruni was interred in the basilica of Santa Croce with an elegant funerary monument showing him reclining with a manuscript on his chest—a copy of his History of Florence.

_______________________________________________________

Excerpt adapted from The Bookseller of Florence: The Story of the Manuscripts That Illuminated the Renaissance. Used with the permission of the publisher, Grove Press. Copyright © 2021 by Ross King.