Girls, Interrupted: A Reading List of Female Madness

Felicia Sullivan on Our Gendered Notions of Sociopathy

The bad girl, the femme fatale, has long occupied the darkest recesses of our imagination. Society demands that women be nurturing and sacrificial, maternal, demure, and compassionate—the very picture of innocence. Not often do we conceive of women giving into their darkest urges, celebrating the wicked and depraved. Leave the savagery and violence for men.

When we think about psychopaths—in fiction and in reality—we think of Patrick Bateman, Ted Bundy, Hannibal Lecter, Iago. It’s rare that you find women painted with the same brutal brush. And although you can find a number of murderous women in literature, I wanted to explore society’s gendered notions of sociopathy.

Are men or women more dangerous? Whom do you fear more when you’re alone and a car pulls up? Or when you’re walking home late at night and you hear footsteps behind you? Usually, the sight of a woman yields a sigh of relief. It’s this sense of safety I wanted to manipulate and use as my main character’s ultimate weapon. My protagonist, Kate, needs others to trust her—because that’s the only way she’s able to escape relatively unscathed.

Below is a collection of twisted tales featuring women who are portraits of evil bearing innocent, beguiling faces. They use their beauty, charm, assumed innocence, and society gendered view of evil as the ultimate disguise. These women don’t seek redemption, nor do they feel remorse. Their greatest desire is self-preservation and satiating their wants, no matter the cost.

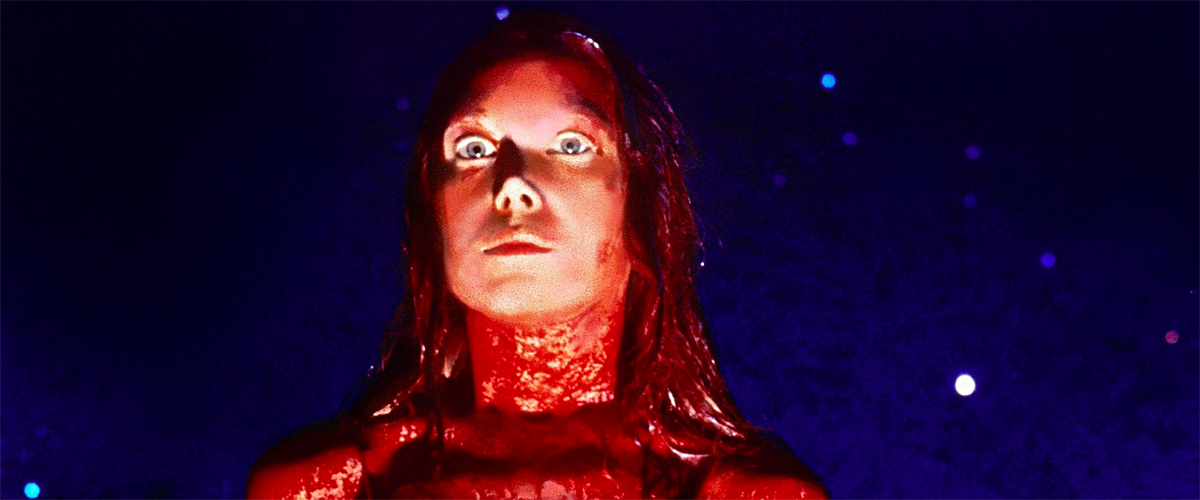

Stephen King, Carrie

The daughter of a strict, abusive, bible-thumping Christian who often locks her in the closet for the tiniest of infractions, Carrie White isn’t like the other gum-smacking girls preening for prom. Carrie is shy, awkward, and strange, which makes her the target of torment and ridicule by a group of girls who could give Regina George or Heather Chandler a run for their money. When Carrie is asked to the prom by one of the most popular boys in school (chided by his girlfriend, who’s sympathetic to Carrie’s plight), her mother-daughter unit comes undone by the threat of hovering sexuality. Prom night, of course, doesn’t go according to plan, and Carrie exacts her violent revenge. However, it’s not until she comes home that the truly chilling scene unfolds—a mother and daughter filled with rage and torment, love, hate, pain, and regret, sacrifice one another for their mutual damnation.

Sheila Kohler, Cracks

What happens to children who are isolated from parental love, locked away in a remote boarding school in South Africa with nothing other than books and vivid imaginations to give them shelter? One hot summer, a beautiful schoolgirl vanishes into the veld. Decades later at a reunion, 13 members of the tightly-knit swim team gather to look back on the weeks leading up to her disappearance. As the memories and secrets unravel, the horrific, violent lengths adolescents will go to when faced with obsession, jealousy, sex, and maternal longing are revealed.

Deborah Levy, Swimming Home

Who’s the mysterious stranger floating naked in the pool? A weeklong holiday in a French villa, shared by two families who don’t like each other very much, slowly unfolds into a forensic examination of anxiety, desire, and mental illness. At the center is a deranged botanist-cum-poet, Kitty Finch, the story’s engine. Kitty’s obsession with a philandering poet—who wants to forget his childhood while his wife’s job as a war correspondent seeks to preserve history—precipitates the characters’ physical and psychological unraveling. While Kitty doesn’t inflict physical violence, her presence (her madness, nudity, and depravity) serves as both a mirror on the broken couple and a window through which they desperately seek escape.

Euripides, Medea

If vengeance called for a coronation, Medea would be its queen. The Greek tragedy centers around a woman scorned seeking revenge against her husband, Jason. Medea shocked Euripides’ contemporaries because she uses the “masculine” traits of intelligence, cunning, and skill to enact vengeance. When writing my novel, I considered how Medea managed to manipulate everyone in her wake, using their sexism as both disguise and weapon. We don’t expect women to be cold and calculating; we never believe they will harm other women or their own children, but Medea shocks everyone by violently rejecting the traditional, nurturing female archetype.

Janet Fitch, White Oleander

Some women were never meant to be mothers. Ingrid Magnussen, a cold, calculating, and murderous narcissist, served as one of the key models in my creation of Kate, who also leads a life of self-absorption at the expense of her family. White Oleander tests the bonds of mother-daughter love and demonstrates the lengths to which people will go in the desperation to forge a family.

Ottessa Moshfegh, Eileen

On the surface, Eileen Dunlop leads a sub-ordinary, if not devastatingly bleak, life. Already considered a spinster in her early twenties, she’s the caretaker of a callous and abusive alcoholic father and spends her days in a juvenile detention center, where her only escape is into her fantasies of a security guard named Randy. Eileen revels in filth and the macabre (the sullied squalor she calls home, the dead field mouse stored in her glove compartment, her frequent use of laxatives and scatological meditations, her fantasy of death by icicle) and pines for freedom from the dreary frigid New England town where she lives. When the elusive and beautiful Rebecca enters the frame, escape becomes real for Eileen, and in a brilliant final scene of cold-hearted violence, the real Eileen emerges.

V.C. Andrews, Flowers in the Attic

When I first read Flowers in the Attic as a teenager, no woman was more terrifying to me than the sweet-faced, tender Corrine Dollanganger (Foxworth). After her husband dies, leaving her family in debt, Corrine moves her children to her estranged, wealthy parents’ home, where she promises their stay in the attic is only temporary until Corrine can regain her father’s love. Locked in an attic for over three years, the Dollanganger children face unspeakable cruelties at the hands of their strict grandmother and their mother, a modern-day Medea, who sacrifices their lives for a sizable inheritance and her own bright future.

Felicia C. Sullivan

Felicia C. Sullivan is the award-winning author of the critically acclaimed memoir The Sky Isn’t Visible from Here (Algonquin/Harper Perennial) and the founder of the now defunct but highly regarded literary journal Small Spiral Notebook. Follow Me Into the Dark is her first novel.