Zainab

On our first orientation day of the MFA program there was nothing about her that would suggest we would be good friends. She seemed suburban to me, married for the second time at twenty-six, wearing lipstick, foundation, and straightened hair that, in my opinion, all worked to hide her natural beauty. She was short and skinny, and on that first day I noticed a nervous laugh that I’d learn to stop noticing later. I like to think back to this day and my first impressions of Zainab. She grew too powerful eventually, like a monster. But on this day she was just a young nervous girl who wanted to write, like I was.

She pursued me. I’m almost sure of that, but memory is a tricky thing. And Zainab wasn’t the kind of person who pursued anything. Everyone pursued her. But this is how I remember it. I had been closest with Stacey, another woman in our program. Zainab slid her way into our friendship. She had been watching us. She must have been. Because she knew exactly how to meet our overly expressive sexuality, our flirtations with faculty, disruptive behavior in the composition-teaching courses we had to take. There is a photo that I’ve since lost in a move of the three of us, all in short, tight black dresses, our brown hair, hips out, arms up as we danced. In the background is a male faculty member watching us. We were always trying to get watched. She convinced me that Stacey was out of control, and gradually she made me all hers.

Zainab was the program’s star. I didn’t know this until I neared graduation. The program director had flown her into the university town and taken her out for dinner. I was just beginning to understand that the world treated Zainab exactly as she demanded to be treated, like a sort of royalty. Zainab grew up in the caste system in India. She had servants. She actually called them that: servants. And she, the oldest and only girl, had been treated like a queen.

She brought one chapter from the novel she claimed she was writing into our workshop. The first chapter. She brought it in again and again, changing it each time. Other times, she passed on bringing her work in. She was sick and couldn’t make it on her workshop days. Or she was going to have to be out of town. Her novel was a thinly veiled fiction of her experience of being physically abused while in an arranged marriage. Over cigarettes and wine she described to me how her current husband had saved her from that marriage. That’s how she said it. He rescued her, as though she had been drowning, as though an enemy had hauled her over his shoulder and run off, and this man had come to retrieve her, like a prince from a fairy tale.

A poet in our program, Tim, pursued her. A top literary agent pursued her even though she had no finished book. These are the sorts of things that happened to her. Meanwhile I forced crinkled paper with my phone number into men’s hands. I left notes to get them to think of me. I got rejections from literary magazines. Zainab had this philosophy that there was enough of everything for everybody. Just because she had something didn’t mean I couldn’t. She only put herself out there when she knew with razor sharp clarity that only good would come back. She didn’t allow rejection.

Eventually Tim rescued her from her marriage, and they moved together to San Francisco. I moved back to Portland with a man who didn’t love me, who couldn’t love me because he was too in love with his drugs, and I worked as adjunct faculty in composition at community colleges. I wrote when I could. Tim applied for jobs teaching composition, and Zainab worked on her book. More agents pursued her, and she was offered a seven-figure, two-book deal from FSG. She had not even finished one of them.

I visited her twice. The first time was to be her maid of honor. The second time was just before she and Tim got pregnant. She showed me the office where she wrote every day. She showed me the vase she thought I got her for their wedding. When I didn’t recognize it, she laughed. I didn’t clarify what I really got them, which was all I could afford. I bought them wind chimes, and I attached a note about how every time they heard it ring they would be reminded of their love. Those chimes were nowhere to be seen, and I felt ashamed. I constantly felt like I was scrambling to be good enough in relation to Zainab and constantly missing the mark. I could never have anything I wanted, but she got everything. What’s more, she expected it. I wish so much I could go back to being that younger Kerry and tell Zainab that she was no better than I was, that I was whole and good and just right.

Zainab almost died while delivering her son. Everything in her life was like this, drama filled and story worthy. She almost died. Really? I asked. Why would I lie about that? And then the baby was here, and she didn’t die. But she started to have problems with Tim. She sent me long, melodramatic letters in which she described how Tim was harmful and terrible and just all-around bad. She sent me emails saying the same thing. One began: “This cannot continue. I cannot go on like this. I whisper my son’s name at night, and pray he will be safe inside his name.”

I wrote her back suggesting that maybe she was caught in a pattern in which men rescued her from other men and she remained a victim. She was furious. She could not believe I would talk to her like this. Didn’t I support her? Didn’t I want her to be happy? Did I think she was a liar? So many women talked to me like this. I didn’t know it then but Zainab was in a long line that had begun with my mother. So I apologized. I had been trained well by my mother and by a handful of other women who I was not to ever suggest weren’t perfect. I was not to ever have a voice in the face of their needs. She wrote back after the apology, praising me for being such a good friend.

The next day, I mailed her a letter. It read:

Dear Zainab,

We are very different people, and I don’t believe we want the same things from our friendship. So, I’m ending it now. I wish you all the best.

Love,

Kerry.

I never heard from her again.Three years later, I saw her image in Vogue. She was as beautiful as always. Her novel had come out, the one she’d been working on since graduate school. I wanted badly to call to congratulate her, but I didn’t. Instead, I started writing. That was when I started writing again, with the ghost of Zainab as my muse.

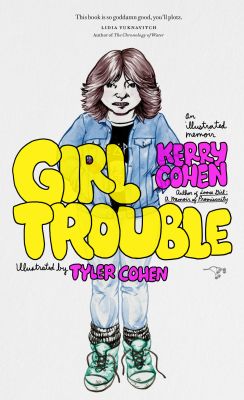

From GIRL TROUBLE. Used with permission of Hawthorne Books. Copyright © 2016 by Kerry Cohen. Illustration copyright © by Tyler Cohen.