Giants’ Bones? Fossilized Testicles? How Humans Reacted to the Discovery of Dinosaurs

Edward Dolnick on Rigorous Yet Humorously Misguided Scientific Inquiry in the 17th and 18th Centuries

For our ancestors in the early 1800s, the discovery of bones and footprints was thrilling, bewildering news. This was not just another scientific discovery, like the sighting of a new moon around a distant planet. This was proof of life where no one had ever imagined it.

Think of modern-day astronomers who believe that we on Earth are not alone. For decades they have turned their telescopes to the heavens, searching for signals in an endless void. So far, nothing.

Scientists and fossil hunters in the first half of the 1800s were the frock-coated counterparts of those present-day searchers. With two crucial differences—they looked back in time, not out in space, and they did detect signs of life.

Not subtle signs either, like odd patterns of static picked up by a computer. Here were teeth like daggers and ribs like rafters.

One of the great hazards in trying to picture the past is forgetting that our forebears didn’t know how their story ended.Poets, scientists, and ordinary men and women looked at the dinosaur discoveries and shuddered and marveled. Tennyson (using an archaic word for “tore”) imagined a bygone world that featured “Dragons of the prime, / That tare each other in their slime.”

Perhaps Tennyson and his peers would have been less astonished if they had anticipated a world that teemed with huge, violent beasts. But the nineteenth century’s aliens turned up out of the blue, as we have seen, and the public was blindsided in a way that people in today’s world—who have known about the search for ET for decades—could never be.

For a moment, try to imagine a modern counterpart. Think what it might be like if people had never dreamed of life anywhere but on Earth. And then picture that one night a spaceship materialized a few dozen feet above Fifth Avenue and proceeded to make a slow and stately tour of Manhattan.

*

One of the great hazards in trying to picture the past is forgetting that our forebears didn’t know how their story ended. We read about the Great Depression or the rise of Nazism knowing how it all played out. It’s hard to bear in mind that no one in the 1930s had that privilege. But we flatten out history’s drama—we miss out on people’s fears and hopes and illusions and expectations—when we bring our present-day knowledge with us on our ventures into past ages.

In the case of the dinosaur discoveries, it wasn’t simply that no one knew how the story ended. More important, no one even knew what to make of how the story began.

That puts the dinosaur story into unusual company. Every once in a great while, people going about their ordinary lives have looked up and seen something they never imagined. A ship with towering masts and billowing sails materialized on the horizon, for instance, in waters that had never known a vessel bigger than a canoe. Or a stranger turned up in a valley so remote that its inhabitants had thought themselves alone in the world.

Of all such first encounters, none ever topped the moment when humans first stumbled on bones, footprints, and other evidence that dinosaurs had once roamed the earth.

What was it like to see what no one had ever seen before?

*

The dinosaur story took on its modern shape around 1800, but it almost began far earlier, back in 1677. In that year, workmen digging in a quarry about twenty miles from Oxford University found a massive bone. They brought it to Robert Plot, a much-admired naturalist and the first curator of Oxford’s Ashmolean Museum. Plot was seldom at a loss—he was always referred to as “the learned Dr. Plot”—but now he stared, perplexed. This was surely “a real bone, now petrified,” he wrote, but whose bone?

The bone was broken at one end, but the break was neat, and the intact piece looked to Plot “exactly” like the lower part of a thigh bone. Except that this femur was huge, at more than two feet around and about twenty pounds in weight. This was, Plot grumbled, too big to make sense. “It will be hard to find an Animal proportionable to it,” he wrote, “both horses and oxen falling much short of it.”

Plot ventured a guess. “It must have been the Bone of some Elephant,” brought to Britain more than a thousand years before when the Romans had invaded.

That was a good idea, but Plot admitted that he had his doubts. Other giant bones had been found in England, he pointed out, and if those were from elephants, too, why was it that no one had ever found any of “those great Tusks with which they are armed”?

And what of other giant bones that had recently been dug up in a churchyard near Bristol? Were those from elephants, too? Plot confessed his bewilderment: “Now how Elephants should come to be buried in Churches, is a Question not easily answered.”

Then came the final blow to the elephant theory. “There happily [i.e., fortunately] came to Oxford while I was writing this,” Plot recalled, “a living Elephant.” This was not an instance of the circus coming to town. Plot meant that his museum had received the skeleton of an elephant from the present day rather than one that had lived a thousand years before.

Plot rushed to compare his mystery bone and other giant bones in the museum’s collection with the elephant’s bones. Nothing matched! So horses were out, and oxen were out, and now elephants were out, too. What was left?

[Plot] was, like all of us, a creature of his own era. Which meant…he could not imagine other eras and other creatures and a world before humans.Plot spelled out the only remaining possibility. “Notwithstanding their extravagant Magnitude, they must have been the Bones of Men or Women.”

By way of support for this eye-catching claim, Plot went on to provide a pages-long list of human giants throughout history. Some had been described by Greek and Roman authors in antiquity, and some were more recent. The physician to the queen of Hungary had declared, about a century before, that “there dwelt a Person within five Miles of him ten Foot high.”

Plot cited other cases. France had boasted a giant of its own, at about the same time that Hungary’s giant was roaming the countryside. The “Giant of Bordeaux” was so tall, reliable witnesses had reported, that “a Man of an ordinary Stature might go upright between his legs when he did Stride.” For Plot, as for many others, biblical accounts carried the most weight of all. “Goliath for certain was nine Foot nine Inches high.”

Case closed! The broken thigh bone came from a giant human being.

From our vantage point, this seems silly. But Plot was not a silly man. He was open-minded and methodical, and he had gathered all the evidence he could find. But he was, like all of us, a creature of his own era. Which meant, in his case, that he could not imagine other eras and other creatures and a world before humans.

Wrong guesses like Plot’s continued long after the learned doctor’s death. Eighty-six years after Plot first pondered it, the giant femur received its first official scientific name. The name reflects a striking fact—almost a century after Plot had decided that so enormous a bone could only have come from a human giant, science continued to endorse the same view.

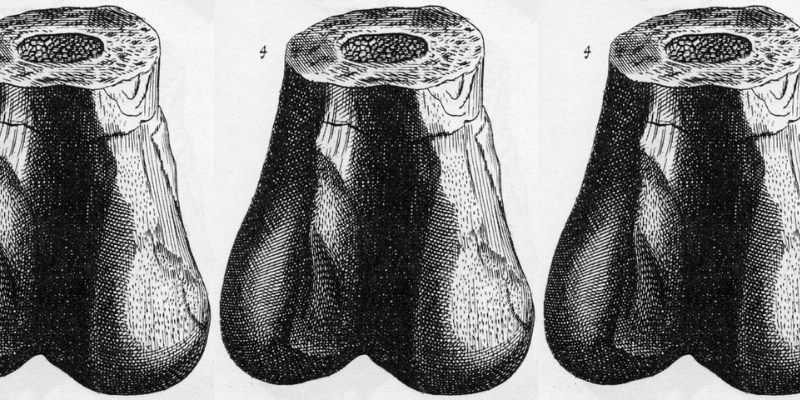

In 1763 an English physician and naturalist named Richard Brookes compiled a six-volume encyclopedia of natural history. Brookes did not have access to the actual bone that Plot had studied, which had been lost at some point along the way. But Plot had drawn it carefully and recorded all its measurements, and that was nearly as good. Brookes reprinted Plot’s original drawing exactly.

This was indeed a petrified relic from a human giant, Brookes concluded, but it had nothing to do with thigh bones. What we had here was plainly a pair of enormous testicles from a bygone human giant. Brookes bestowed an imposing Latin name on the fossil, Scrotum humanum. (A French naturalist named Jean-Baptiste Robinet took matters a step farther, in the same misguided direction, by identifying signs of musculature and a bit of urethra.)

The bone would eventually be properly identified, but not until 1824. It would take that long to come up with an explanation that would have struck Plot and his successors as far more outlandish than a world replete with human giants.

__________________________________

Excerpted from Dinosaurs at the Dinner Party: How an Eccentric Group of Victorians Discovered Prehistoric Creatures and Accidentally Upended the World by Edward Dolnick. Copyright © 2024 by Edward Dolnick. Reprinted by permission of Scribner, a Division of Simon & Schuster, LLC.