“Giacometti Slept with the Lights On...” And Other Encounters with Mid-Century Art Stars

Barbara Chase-Riboud Has Some Stories to Tell

After graduating Yale’s School of Design and Architecture in 1960, the visual artist and writer Barbara Chase-Riboud moved to Europe and spent decades traveling the world and living at the center of artistic, literary, and political circles. Here, she details some of the people she encountered in a brief essay.

*

Traveling in celebrity circles in the 1960s and 1970s, I was amazed at how different my reactions could be, ranging from indifference to Salvador Dalí to exasperated affection for Henri Cartier-Bresson, who woke us up every morning by calling on the phone to see if we were up. He reciprocated with “I love her but sometimes I would like to wring her neck.”

Why was there such a maternal reaction to Giacometti, who slept with the lights on because he was afraid of the dark? I remember every second of my first and second meeting with him and have completely forgotten the afternoon I spent with Le Corbusier.

I first met Alberto Giacometti in 1962, as a very young woman newly married to Marc, who had asked his mentor Henri Cartier-Bresson to look after me while he was away on a photographic trip to Cambodia as I didn’t speak a word of French. Cartier-Bresson took me to see Giacometti at his studio at 46 Rue Hippolyte-Maindron in the 14th arrondissement in Paris.

Why do I remember the gentle sweetness of Pierre Cardin, who became a collector, and can’t think of one thing François Mitterrand said to me?

It was the most rundown, decrepit habitation I had ever seen—made of wood planks and an iron roof, crumbling stairs and no windows except a skylight. It was tiny, no more than five meters by five meters. Everything was covered in plaster—the walls, the floors, the ceiling—and the first time I saw him, he himself was a walking Egyptian mummy, entirely white, covered in white plaster from his shoes to the Afro curly hair on his head: his clothes, his hands, his feet, and his cigarette, which dangled from his lips and from which a long curl of white smoke escaped. The last time we saw him alive was in late 1963 or early 1964 wandering through the great dome of Milan as if he was lost. We raced up to him and asked him what was wrong? What was he doing there all alone?

“Maestro, can we help you?” we said.

“I’ve lost my train ticket for Gaubunden,” he said.

We bought him another ticket, fed him high tea at the Biffi Scala in the galleria, and put him on the train to his mother’s house in Borgonovo.

Why do I remember the gentle sweetness of Pierre Cardin, who became a collector, and can’t think of one thing François Mitterrand said to me?—or be moved by the ravished beauty (not a trace left) of Lee Miller but not of Julie Man Ray’s splendor?—by the jaw-dropping, heart-thumping surprise of Josephine Baker singing “I Have Two Loves, My Country and Paris” while forgetting I met Bertrand Russell in London—twice?

There were celebrities like Ben Shahn who became collectors and Man Ray who lived down the street from us and who was family. I swooned over Alan Bates’ looks and took the archangel beauty of Robert Redford with a grain of salt—stunned by Stephen Boyd but indifferent to Charlton Heston’s watercolors he drew on the set. Physical beauty in any and all shapes—female, male, or genderless, always moved me. Intellectual genius I also considered a kind of Beauty. But I fell hopelessly in love with Sandy Calder, my neighbor in Saché. What made me stand transfixed before the white-suited, white-haired presence, abjectness of Ezra Pound and only giggle with James Baldwin, my heart’s hero? I stood in jaw-dropping adoration before the old Henry Miller and not the young Alain Delon. Dizzy at meeting Zhou Enlai and not the king of Greece, weeping over Simone Signoret’s faded looks but not Jeanne Moreau’s.

Beauty became a narcotic; landscape was wine, architecture was whiskey, painting was cocaine, and sculpture was heroin.

Sitting at a feast table, I was not celebrity-hungry. For a little American girl from Philadelphia, I was almost oblivious, as if I thought this can’t be happening so I might as well ignore everything around me. I spent a lot of the time dreaming, instead, of taking notes or photos. Cartier-Bresson scolded me for being late to my own opening. He was emphatic on celebrity politeness—you showed up, you smiled, you answered questions if you had an interview, you were on time, you wrote thank-you notes, you ate whatever was on your plate. But then he never accepted interviews nor people’s invitations to dinner in the first place.

I could never acknowledge the passing of time, which I believed I never had enough of so perhaps this was the reason I passed so much of it in oblivion. Beauty became a narcotic; landscape was wine, architecture was whiskey, painting was cocaine, and sculpture was heroin. Churches, palaces, chateaux, gardens, fountains, frescos, statues, reliefs became my religion and my fix.

The one thing all these celebrities had in common was a kind of homelessness; they were nonspecific entities unto themselves. They “belonged” nowhere, in no time, place, or race. As Man Ray pointed out many times, he loved being an alien. What made them unique, self-contained, enclosed, and barricaded in a universe of their own—what was celebrity? Being perpetually alone in your own world with fame-hungry people milling around you? Finally living with the debris of your own beauty? Was this also the fate of works of art? Of beauty both physical and intellectual and subject to the lens of a camera like Marc’s? For a long time, I wasn’t disciplined enough to ask myself that. But I began to notice that Marc didn’t see people except through the lens of his camera and he didn’t listen to people except over the telephone . . .

The Museum of Modern Art in New York premiered the Seagram documentary film called Five presenting five American artists: Bearden, White, me, Hunt, and Blayton. In an amazing and ironic closing of the circle, there was Rene Burri of the 1958 Valley of the Kings fame and Marc’s best friend to whom we had both written “Dear John” letters on the same day, announcing our marriage plans, who filmed the artists in their studios. Closely following the Schaefer show was the Whitney Annual, the first time a Black American woman had been included, which led to an invitation by Peter Selz, the former director of MoMA, to do a one-person exhibit at the Berkeley Museum in California.

At the same time, I was exhibiting in Europe— France, Belgium, Italy, and Germany—and Canada. There was an explosion of activity at the Bonvicini Foundry and much coming and going between Paris and Verona. Even my letters to my mother increased as did my visits to the States besides her coming every year to Europe. I even exhibited in my mother’s Canadian hometown, Toronto. I retrieved my London friends from my Stirling days and even cast sculptures at the Royal College of Art. James’ reputation had ballooned internationally along with his fame, and he had married a colleague architect Mary Shand. Marc’s activity didn’t wane either, so we kept to schedules that, as my housekeeper put it, “the defense minister of France would keep.”

Once, we crossed paths in Charles de Gaulle Airport totally by chance. I was coming from Germany and he from India. We decided the kids could wait and booked ourselves into the Hotel Raphael near the Étoile—the best and most luxurious hotel in Paris for the night—with no luggage. Imagine the director’s surprise when our passports revealed that we were married—to each other . . . I was determined to have it all: perfect wife, perfect mother, perfect sculptor, perfect poet, perfect Frenchwoman. And always Queen Lizzie smiling in the background as I danced as wildly and frantically as Josephine ever had, making things look easy . . .

__________________________________

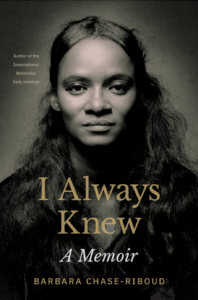

Excerpted from I Always Knew: A Memoir by Barbara Chase-Riboud. Reprinted by permission of Princeton University Press. Copyright 2022.

Barbara Chase-Riboud

Barbara Chase-Riboud is a visual artist and sculptor, novelist, and poet. She is the author of six novels, including Sally Hemings and The Great Mrs. Elias, and three poetry collections. She is the recipient of many awards and prizes, including the French Légion d’Honneur in 2022. She lives in Paris and Rome.