On the day I was born, 3rd August 1986, “The Edge of Heaven” by Wham! was number one. Since I can remember, an annual tradition was playing it as loud as possible as soon as I woke up. I remember all the birthdays of my childhood through the sound of George Michael’s defiant “yeah, yeah, yeah”s in the opening bars—jumping on my mum and dad’s bed in my pyjamas, eating sprinkle sandwiches for breakfast. It is why my middle name is George—Nina George Dean. This mortified me throughout my adolescence when my flat chest and certain jaw gave me a masculine enough energy without also being named after an ageing male pop star. But like all abnormalities and embarrassments of childhood, adulthood recalibrated them into a fascinating identity CV. The weird middle name, the birthday breakfast sandwich spread thick with margarine and dipped in hundreds and thousands—all of it strung together to form my own unique mythology, which I would one day speak of with bewildered pride to airtime and intrigue.

Mortifying oddity + time = riveting eccentricity.

On my thirty-second birthday, 3rd August 2018, I brushed my teeth and washed my face while playing “The Edge of Heaven” from the speakers in my living room. Then I spent the day on my own, doing and eating all the things I loved the most. For breakfast, I had a poached egg on toast. I can confidently declare at thirty-two years old that there are three things I can do flawlessly: arrive anywhere I need to be on time with five minutes to spare; ask people specific questions in social situations when I can’t be bothered to engage in conversation and I know they’ll do all the talking (Would you say you’re an introvert or an extrovert? Would you say you are ruled by your head or by your heart? Have you ever set anything on fire?); and poach an egg to perfection.

I checked my phone and found a grinning selfie of my parents wishing me a happy birthday. My best friend, Katherine, WhatsApped me a video of Olive, her toddler daughter, saying “Happy birday, Aunty Neenaw” (she still couldn’t get it quite right despite extensive tutoring from me). My friend Meera sent a gif of a luxurious-looking long-haired cat holding a Martini in its paw with the message “cannot wait for tonight, birthday gal!!!!!,” which meant she would certainly be in bed before eleven. This is what happens when people with children get too worked up for a night out—they tire themselves out with anticipation, set themselves up for a fall with their bravado, get stage fright then ultimately go home after two pints.

I walked to Hampstead Heath and went for a swim in the Ladies’ Pond. On my third circuit, the inoffensive lick of summer rain began to fall. I love swimming in the rain and would have swum for longer had the matronly lifeguard not ordered me to get out for “health and safety reasons.” I told her it was my birthday and thought this might grant me an off-the-record bonus circuit, but she informed me that if there was lightning, it would directly strike me in the open body of water and “fry me like a rasher of bacon,” not a mess she wanted to clean up—“whether it’s your birthday or not.”

I came home in the afternoon, to my new flat and the first home that I’d bought. It was a small one-bed in Archway, on the first floor of a Victorian house. The estate agent’s generous description of the property was that it was “warm, eccentric and in need of modernization”—it had a carpet the colour and texture of instant coffee granules, a peach-tiled eighties bathroom replete with abandoned bidet and two broken doors on the pine kitchen cupboards. I was sure it would take as long as I lived there to afford to do it up, but I still felt lucky every morning I woke and looked up at the swirly crusts of my Artex ceiling. I never imagined I would ever be able to own a flat in London—the actualization of this once-impossible dream alone made it the best place I’d ever set foot in.

This is what happens when people with children get too worked up for a night out.I had two neighbours: an elderly widow named Alma who lived above me, whose hallway small talk about how best to grow tomatoes on a windowsill and generous donations of leftover homemade kibbeh were both delightful; and a man downstairs, who I hadn’t yet met despite having moved in a month ago and made a number of attempts to introduce myself. I’d knock, but there was never an answer. Alma said she’d never spoken to him either, but she did once talk to his female flatmate about the building’s electricity meter. I only heard him—he came in from work at six o’clock and made virtually no noise until midnight when he cooked and ate his dinner and watched TV.

I scraped together the money for the flat with savings, the royalties from my first book, Taste, and the advance on my second cookbook, The Tiny Kitchen. Taste was a recipe book, inspired by my family’s cooking, my friendships, my only long-term relationship, my travels and my favourite chefs. It also had a thread of memoir spun in between the recipes. There was an overarching theme of discovering my own tastes in life as I learnt about my culinary ones—what I liked and what satisfied me. It told the story of how I’d balanced a night- and-weekend occupation as a supper club owner with my day job as an English teacher at a secondary school, and how I eventually saved enough to quit and become a full-time food writer. It also touched on my relationship and ultimate amicable break-up with my first and only boyfriend, Joe, who was supportive of my decision to write about us. The book was a surprise success and off the back of it I got a column in a newspaper supplement, a number of soul-destroying but bank-account-enhancing partnership deals with food brands and a further two-cookbook deal.

The Tiny Kitchen, which I had just completed, was about what I’d learnt from cooking and entertaining in a rented one-room studio flat with no kitchen storage space, an oven the size of a Fisher-Price cooker and only one hotplate for a hob. It was my first solo home after Joe and I broke up. I preferred to talk about my third book, a temporarily unnamed project about seasonal cooking and eating, which was in its proposal stage. I’d now learnt from years and years of writing that the very best version of a piece of work was when it was still just an idea and therefore perfect.

I ran a bath and put on a long-loved iTunes playlist that was called “Pre-lash” in my twenties, which I’d renamed “Good Times” in recent years, to mark a move away from reckless, bodily abandon and towards mindful, considered pleasure. I created the track-list to listen to before a night out when I was a first year at university and the shape of its journey played out in full was always in tandem with the same tireless rituals of feminization I had been following for fifteen years: wash hair, dry it upside down and try to increase its volume by ten per cent, pluck upper lip, two layers of mascara, second drink, walk into two spritzes of perfume—by the time the penultimate track came around (“Nuthin’ but a ‘G’ Thang”) a cab was always waiting outside while I cut my legs to ribbons with a disposable razor over the sink because I’d forgotten to shave them in the shower.

My hair was back to its natural dark brown and cut to shoulder-length. There was a recent addition of a fringe to hide the new creases in my forehead, as light as concertinaed tissue paper, but visible enough for me to want to not think about. Luckily, I saved time when it came to make-up. My face had never worn make-up well. I was grateful, as I already felt grooming took up far too much time and was a constant source of feminist guilt, along with my total disinterest in all DIY and all sports. Sometimes, when I felt despondent, I liked to calculate how many minutes of my remaining life I would spend removing upper lip hair if I lived until I was eighty-five and think about how many languages I could have learnt in that time.

_______________________________________

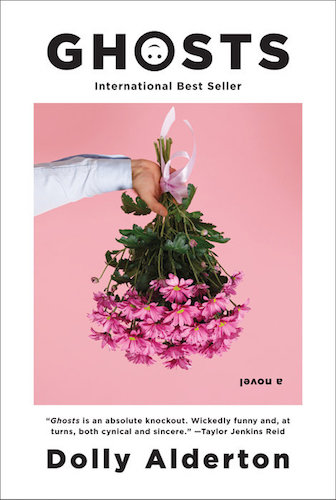

From the book GHOSTS by Dolly Alderton. Copyright © 2020 by Dolly Alderton. Published by Alfred A. Knopf, a division of Penguin Random House LLC. All rights reserved.