On weekends my mom drove us to art classes, even on Saturday mornings, even to the other side of town, even in the middle of winter when the streets were covered in snow.

In my very first memory of painting, the teacher held up a laminated print of Van Gogh’s Starry Night. She scattered orange and yellow oil pastels across the table, and taught us to press curving dashes into the paper to make stars. We swirled deep blue watercolor and swept it over the dashes. As the blue water settled around the edges of the orange and yellow marks, I gasped, watching the stars emerge against the night sky.

Only recently did I think to ask my mom, Why did you take us to so many art classes when we were kids?At home, I practiced painting starry nights, while my sister drew fat multicolor cats. The floor rippled with paints and pastels. The walls danced with our art.

*

People often asked me, Do you come from a family of artists?

And I would say, There are no other artists in my family.

Only recently did I think to ask my mom, Why did you take us to so many art classes when we were kids?

My mom said she had always wanted to draw, but didn’t know how to do it well. She thought if my sister and I learned how to draw, then we would be able to draw whatever we wanted.

She said, Lik bat chung sam—do you know what it means? It means, what your heart wants but you cannot do. It is an uncomfortable feeling. It’s the feeling of wanting to do something and not being able to.

*

In my last year of high school, my mom asked me to make a painting for my dad. The Feng Shui master advised my dad to hang one in his apartment, on the wall behind his chair at the head of the dinner table.

The painting has to have nine horses, my mom told me. They have to be galloping.

I went to the art store and picked out sturdy stretchers and thick cotton canvas. I bought a new set of Windsor & Newton oil paints and different sizes of soft sable brushes. I bought a brush cleaner jar with a metal coil inside, and a new can of odorless mineral spirits. I searched online for an image of nine horses galloping, but I couldn’t find one, so I took an image of six horses galloping and an image of three horses galloping from the same perspective, and photoshopped them together. Then I painted the canvas with a ground of yellow ochre, sketched the outlines of the horses with burnt sienna, and blocked out the dark areas with raw umber.

Choi yung sat ma—do you know what it means?It’s a proverb about an old man who was sad because he lost his horse. But it was a good thing in the end.When I started hearing back from colleges, I stopped painting. I couldn’t sleep at night. My hair fell out when I touched it. I didn’t look in the mirror because every day my face grew a new pimple.

In the end, I was accepted to two colleges. Deciding between the two, I called my dad to ask for his advice.

It’s up to you, he said. Both are good, but neither one is Harvard.

When my mom saw me slouched over my desk that night, she said, Choi yung sat ma—do you know what it means?

It’s a proverb about an old man who was sad because he lost his horse. But it was a good thing in the end.

Why was it a good thing?

I don’t remember, but the point of the proverb is, what you think is bad might be good, and what you think is good might be bad. Choi yung sat ma, that’s what it means.

I spent the months after that studying for my provincial exams, driving around with my friends, and packing my suitcases. Then I left for college.

Four months later, when I came home for winter break, my mom asked me when I was going to finish the painting.

I don’t know, I said. I don’t make realistic paintings anymore.

So my dad went to a painting factory in Shenzhen and hired a painter there to make one for him.

In the painting, nine horses gallop through a lush forest clearing, their manes gilded orange by the rising sun. My dad hung the painting in his apartment, behind his chair at the head of the dinner table, in a three-inch carved golden frame.

__________________________________

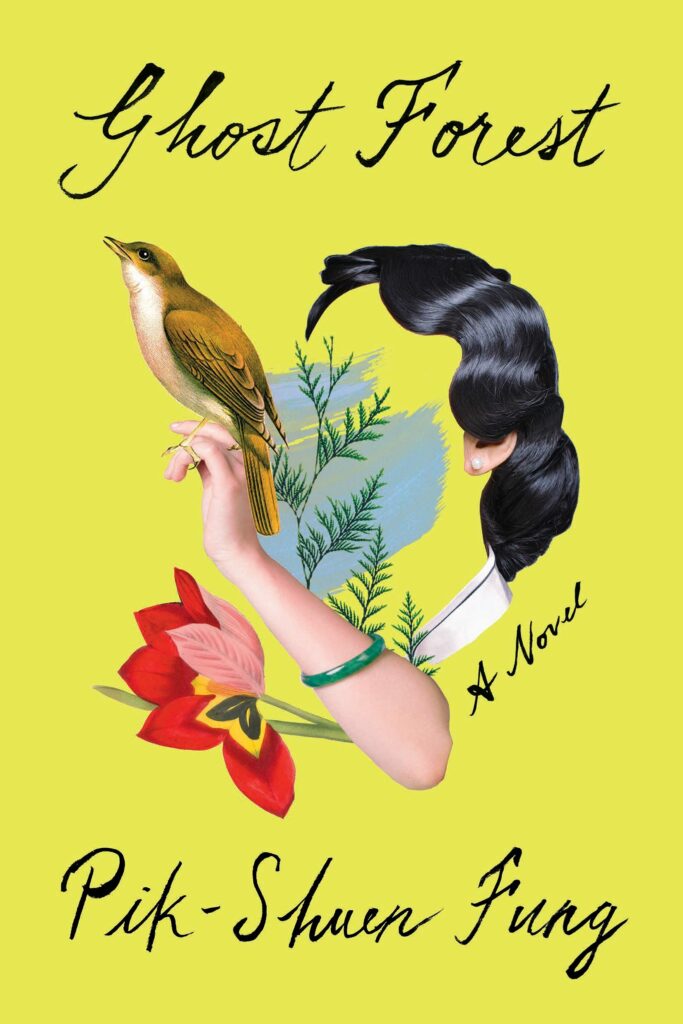

Excerpted from Ghost Forest by Pik-Shuen Fung, Copyright © 2021 by Pik-Shuen Fung. Excerpted by permission of One World, an imprint and division of Penguin Random House LLC, New York. All rights reserved. No part of this excerpt may be reproduced or reprinted without permission in writing from the publisher.