Getting to Know the Great John Prine

Tom Piazza on His Inspiring Encounters With a Folk-Country Icon

I first saw John Prine perform in December 2016, at New Orleans’ Saenger Theatre. I had known his songs and his records for years, and the mental image of him that I carried into the Saenger was somewhere between the wistful-looking, beardless young fellow sitting on a hay bale on the cover of his 1971 self-titled first album, and the cocky desperado of two years later on the cover of his album Sweet Revenge, wearing a denim shirt and jeans, a beard, and aviator shades, smoking and reclining on the front seat of a convertible.

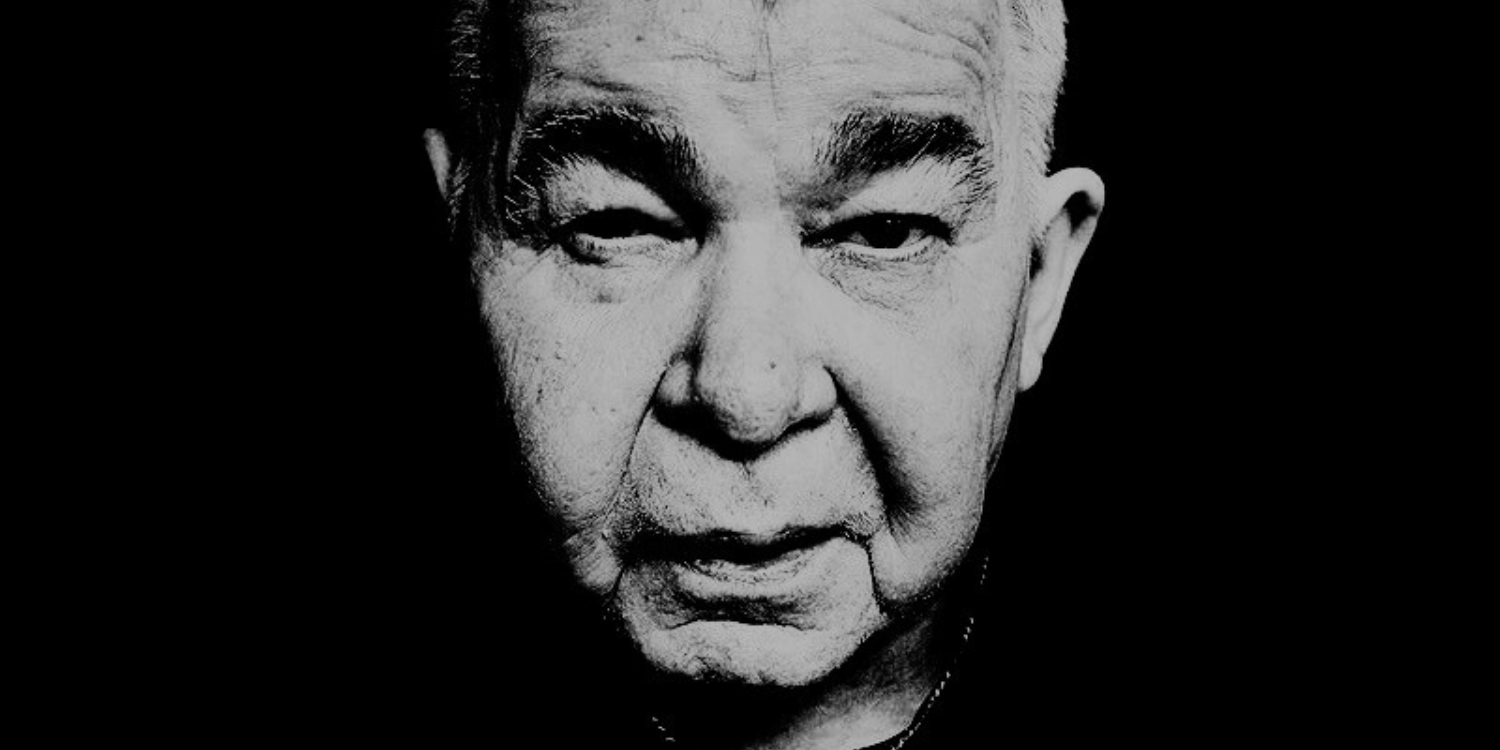

But that December night at the Saenger an old man took the stage—patchy filaments of gray hair on a head the size and shape of a slightly deflated soccer ball, and a dark blue suit with the jacket buttoned over a bulging stomach, the head cocked downward slightly to one side. He might have been an aging Mafia don, or an organizer for the longshoremen’s union, playing a Gibson jumbo guitar that looked almost as big as he was. Accompanied by a small group, he played through some of his well-known songs and some of his lesser-known songs. It was a good show, although he seemed a little tired.

What I remember most about that moment was a feeling of plain, pure happiness, almost as if we were already friends.

At one point the band left him alone onstage in front of the sold-out hall to sing “Mexican Home.” The song originally appeared on Sweet Revenge, with Prine’s raspy voice belting it out over a bump-and-grind arrangement played by a full band. But the version at the Saenger was a different song entirely—quiet and haunting, delivered in a rocks-and-gravel voice to a dark hall that had gone dead silent. Sharp images flashed through the lyrics—nighttime heat lightning, headlights from passing cars, the fan in the window, the door propped open by a broom, the air “as still as the throttle on a funeral train.”

It all cast a deep spell, and you had to wait until the final verse to know that the song was a tableau of the day the singer’s father died in 1971. At one point I realized that tears were running down my cheeks. That lone figure onstage, ravaged by time and circumstance, yet standing there delivering this painful beauty into the cavernous theater, alone…It occurred to me right then that I might want to write something about him, although I wasn’t sure just what, or why.

I hadn’t written a profile of a musician, or of anyone, for twenty-two years, since I’d spent a couple of days in Nashville with the bluegrass singer and hell-raiser Jimmy Martin, culminating in a wild climax at the Grand Ole Opry. That article, which appeared first in the Oxford American, had subsequently come out as a little book titled True Adventures with the King of Bluegrass. Generally speaking, I don’t enjoy pointing a microphone at people and asking them questions. What there was to know, I thought, was in the experience of them, not in any answer they put forward to a question. But a year after that Saenger concert, word came that John Prine would be returning to New Orleans, in February 2018, this time to play the Orpheum Theater, and through his management we made arrangements to meet.

At the Orpheum, Prine played with a vigor and humor that was a world away from the show I had seen in December 2016. The band was slightly enlarged—now including multi-instrumentalist Fats Kaplin along with guitarist Jason Wilber, bassist Dave Jacques, mandolinist Pat McLaughlin, and drummer Kenneth Blevins—as was the show, which ran a full two hours and included two new songs, “The Lonesome Friends of Science” and “Summer’s End,” which would appear on his soon-to-be-released record The Tree of Forgiveness, his first album of original songs in almost thirteen years. Prine emitted funny anecdotes and commentary between songs, and on the closing number, “Lake Marie,” he went into full rockabilly mode, knocking his knees together with the band riffing behind him and finally taking off the guitar, setting it on the stage boards in front of him, and doing some unnameable ritual dance around it before strutting offstage slowly in time to the music, grinning and soaking in the screams and hollers from the standing audience.

After the show, John’s wife and manager, Fiona Whelan Prine, greeted my partner Mary and myself out in the audience rows and brought us back to meet John. Fiona was gracious and friendly, and also clearly alert and observant—we were, after all, being checked out. We stepped over the cables and past the stagehands moving crates and wheeling speakers around, and into a snug, cozily lit dressing room, where John was standing, waiting for us. He had changed into a dry black T-shirt and jeans, and he was smiling in a peculiar, disarming way, as if we were somehow both in on a joke. Warmth came off of him, and also the sense of someone inside watching from a few rows back.

We told him how much we loved the show, told him about seeing him at the Saenger a year or so earlier, made chitchat. I had brought a copy of True Adventures with the King of Bluegrass with me, and after a few minutes I handed it to him, saying that I thought he ought to have some idea of what he might be getting into if we did an article. He smiled and chuckled and accepted the slim volume, and after looking at the cover for a couple of seconds he said, “I have this!”

“What?” I said. “Really?”

“Yeah,” he said. “I have it. I sent off for it with money I made singing!” He said this with a big proud grin, like a newsboy who had just won first prize in a sales contest.

I told him that I could take it back if he’d rather not carry something he didn’t need while he was traveling, but he shook his head.

“No, I want this one,” he said. “I want a signed copy! You have a pen?”

I signed the book, and the four of us stood around talking for ten minutes or so, and it was very relaxed and fun. They were, clearly, both careful observers, and they knew how to put you at ease while sizing you up. After a while, they needed to get themselves together, and an old friend of John’s, wheelchair-bound, was waiting outside to visit with him, so we said our goodbyes, agreeing to reconvene and see about making a plan.

*

The Tree of Forgiveness had just come out when, a month after our 2018 meeting at the Orpheum, I drove to Nashville, followed directions to an address in an upscale neighborhood south of downtown, and made a left into a long downhill driveway edged by a broad manicured lawn ending in front of a grand white-columned mansion.

John came to the door and welcomed me in, once again wearing a black T-shirt and jeans, which seemed to be a kind of uniform for him. The entry foyer was impressive, high-ceilinged, with a long, curving stairway leading up to the second floor. They had only just moved in a few days before, and Fiona told me that I was their first visitor. We walked past a bright, airy dining room and a big living room, still barely furnished, with windows looking out onto a shaded pool area, and then into a clubby-feeling library room, with ceiling-high shelves full of books. At the far end was a fireplace with a large-screen TV mounted on the wall above it, and, in a corner, a guitar on a stand.

The three of us sat down and made conversation for a while. It was just as relaxed as it had been backstage at the Orpheum, and John made a point of asking me about myself—my books, where I was from, and if I played music. I do play guitar, mostly in the style of Mississippi John Hurt, the great blues singer and songster. Hearing this, John stood up, retrieved the guitar from its stand at the end of the room, brought it back, and handed it to me.

Was I being auditioned? If so, for what? John was so disarming that I didn’t think, I’m going to be playing guitar in front of John Prine! It felt as natural as could be, and I started Hurt’s “I’m Satisfied,” a ragtimey fingerpicking tune. Halfway through, John started singing along. What I remember most about that moment was a feeling of plain, pure happiness, almost as if we were already friends. There was no proscenium; we were just sitting there, for that minute or so, making music together.

Not only had he endured in the face of all the looming mortality, he continued to stand up and make defiant beauty in spite of it all.

Fiona left the room to prepare a snack, and I asked John about his song “Mexican Home,” which I’d heard him play solo at the Saenger. It had a deceptively tricky fingerpicking pattern, and I asked if he could show it to me. He did, running through it a couple of times before handing the guitar back to me and talking me through it until I had it down. After a few more minutes we headed to the dining room, but not before John stepped to the bookshelf and pulled down a copy of a biography of Hurt that had just been published.

“Take it,” he said. “Bring it back when you’re finished.” I noted the implication that we would be getting together again.

We walked through the foyer, got ourselves settled at the long, banquet-sized dining table, and Fiona served tea and scones as we chatted. They were about to begin touring in support of The Tree of Forgiveness, and Fiona handed me one of the first copies of the CD, with its startling cover, a close-up frontal portrait of John’s face, staring directly out, stunned, ravaged, and unsmiling.

At the table John was sweet, funny, a bit reserved, self-effacing as he confessed to being a little nervous about the upcoming tour. We talked some more about music, and family, and finally, after my third cup of tea and my second scone, Fiona fixed me with a friendly but no-nonsense gaze and asked, “So what is it you want to do?”

I had been asking myself that same question. I was forty-one when I wrote True Adventures with the King of Bluegrass. On that day at the Prines’ I was about to turn sixty-three. In between, I had written novels, books of nonfiction, several seasons of a television series, and, like many other New Orleans residents, had lived through Hurricane Katrina and rebuilt a life in its aftermath. But somewhere in there while I wasn’t looking I had crossed a line. People only a few years older than myself had started disappearing with unsettling frequency. Mortality was suddenly the wallpaper in the room.

Prine’s health issues of the previous couple of decades were no secret—the throat cancer, the operation for lung cancer, and God knew what else. But at that recent New Orleans appearance he had damn near burned down the Orpheum Theater. He didn’t look like somebody with one foot in the grave. Not only had he endured in the face of all the looming mortality, he continued to stand up and make defiant beauty in spite of it all…

I stumbled over a bunch of words to this effect—what I was trying to express was still unformed in my mind, and maybe not even sayable in words—as Fiona and John listened closely.

Fiona excused herself to get more tea from the kitchen, and when she left, John said, “That kind of surprised me, that she asked you that.”

“Well, I know it’s what she’s supposed to do,” I said. “But that’s really the best answer I could give. If it’s even an answer. Like with writing a novel—I can’t make a plan from beginning to end and then execute it.”

“Yeah—if you knew how it was going to end, why would you write it?”

“Exactly.”

Fiona came back in, asked a few more questions, seemed satisfied, and nodded her approval. I looked at John.

“Sounds good to me,” he said.

__________________________________

Adapted from Living in the Present with John Prine. Copyright © 2025 by Tom Piazza. Used with permission of the publisher, W. W. Norton & Company, Inc. All rights reserved.

Tom Piazza

Tom Piazza’s books include the nonfiction bestseller Why New Orleans Matters and the novels The Auburn Conference and A Free State. He is a four-time winner of the ASCAP Deems Taylor Award for Music Writing. He lives in New Orleans.