Getting Lost in the Libraries of Paris Researching WWII

Janet Skeslien Charles Finds Her Way to Her New Book

The American Library in Paris sits in the shadow of the Eiffel Tower. Its collection of 100,000 books is spread over three stories. Members from 60 countries can work at long tables or whisper at the coffee machine. As the programs manager, I oversaw the ALP’s weekly Evening with an Author series, hosting journalists, debut novelists, and National Book Award winners. At events, I stood in the back of the reading room, one eye on the crowd, the other on my journal as I jotted down the writers’ words. During the day, at my desk in the bustling back office, I also took note of what colleagues said and was particularly captivated by the World War II story of the courageous librarians who defied the Nazi “Library Protector” in order to hand-deliver books to Jewish readers.

During the Nazi occupation of France, Dorothy Reeder, the Directress of the Library, stood up to the Bibliotheksschütz, Dr. Hermann Fuchs, who had full authority over intellectual activity in the country at the time. Before the war, these two book lovers had chatted at international library conferences; later, they would find themselves on opposing sides. I longed to learn more about them, and began searching for answers to my questions: What had brought the Directress to France? What became of her? Who was the Bibliotheksschütz before the war? Was he eventually arrested for his role?

Worried that nothing would come of my research, I was reticent to tell coworkers about the project. But I wasn’t shy about reaching out to strangers and sent dozens of emails to various libraries where the Directress and her staff had worked. I contacted people with the last names of Reeder, Netchaeff, or Oustinoff in hopes that they were related to the ALP librarians. I read through hundreds of pages of scanned documents from the American Library Association archives, including Dorothy Reeder’s correspondence. I interviewed French women who’d lived through the Occupation.

To learn more about the day-to-day life of Parisians during the war, I turned to the Bibliothèque Nationale de France (BNF). This modern library is made up of four buildings in a configuration that resembles four open books; however, the public resources are less accessible than this design would suggest, with the tomes for the general public on the basement level and the research library in the sub-basement.

In keeping with the infamous French bureaucracy, to access the research level, you must have a letter from a professor or an employer and go through an interview. I wasn’t a student, and since I’d recently dedicated all my time to research, I no longer had an employer. An Ivy-League acquaintance was rejected after her interview, and I became nervous that I wouldn’t pass the test.

In preparation for my appointment, I carried a list of books to consult as well as a copy of my first novel, physical proof that I was an author. The reference librarian conducting the interview was cordial; we discussed my project for 20 minutes. She hadn’t heard of the librarians who’d resisted during the war, which made me want to write the book even more.

With a stamp of approval on my application, I moved to the cashier’s desk. A researcher’s pass costs 50 euros, or $70, for a year.

“What’s your profession?” the cashier asked.

“I’m an author.”

She glanced at the paperwork. Not finding the appropriate box to check, she said, “We’ll just write that you’re unemployed.”

Library card in hand, I passed through immense metal doors and down two narrow escalators, to a last set of doors that older researchers have trouble opening without assistance. With 40 million documents, the BNF houses the national memory and much of the international memory. All precautions against fire are taken. It feels like a bunker.

Library card in hand, I passed through immense metal doors and down two narrow escalators, to a last set of doors that older researchers have trouble opening without assistance.I devoured the history books and memoirs I found there, yet what I appreciated the most was the gorgeous collection of the Paris edition of the New York Herald Tribune. Turning the crisp pages, I delighted in the news of the “American Colony” in the City of Light before perusing the ads for everything from cigarettes to girdles. I consulted back issues of Library Journal to better understand the concerns of librarians in the 1940s. I thought that germs were a recent concern, but it turns out that even then, patrons worried about transmission of germs through borrowed books. There was an article about librarians who asked customer service experts at a department store for advice in order to better welcome patrons. Of course, there were articles about quirky patrons—some things never change.

With tired eyes, I returned home, head full of the past as I crossed over the Seine River and continued to my apartment. After dinner, I resumed my research. I’d become an obsessive Googler.

This 1930s information card of the American Library in Paris is one of my early finds.

Photo credit: the American Library in Paris archives

Photo credit: the American Library in Paris archives

Photo courtesy of the author

Photo courtesy of the author

I purchased this photo from the archives of the Chicago Tribune and it became the inspiration for my character Margaret. I love the wide brim of the women’s hat and wonder what secrets she’s hiding.

I felt a thrill when this 1936 portrait suddenly became available on eBay. Even though the photo only cost $24.99, it has been the best purchase of my life. From a place of honor on my desk, Miss Reeder spurred me on through 75 rejections from agents. When I was feeling down, I reminded myself that the Directress had faced the Nazis; I could keep sending query letters.

Photo courtesy of the author.

Photo courtesy of the author.

Thanks to les Pages Blanches, the White Pages, I learned that the son and daughter of Boris Netchaeff, the Franco-Russian head librarian, lived a short train ride away in Normandy. Now in their eighties, the siblings have different views about their family; Hélène attributed it to the fact that she was born before the war and was old enough to remember everything. She was in the next room when her father was shot by the Gestapo and remained at his side through his recovery. Over lunch with Hélène and Oleg, my discoveries were also theirs: as one sibling spoke, the other would say, “I never knew that.” When they discussed Boris, I had the impression that each was describing a completely different man.

Photo credit: Hélène Netchaeff

Photo credit: Hélène Netchaeff

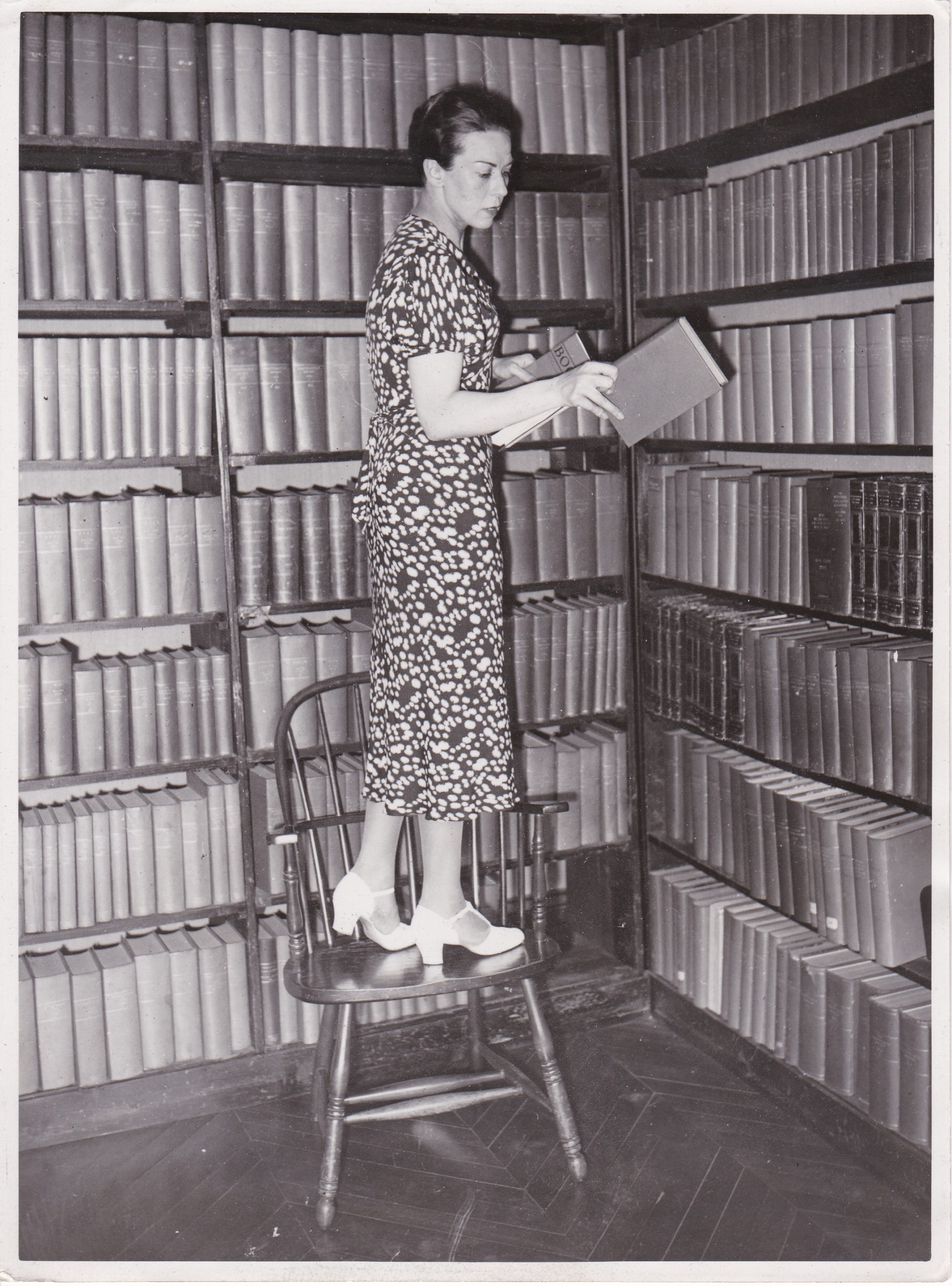

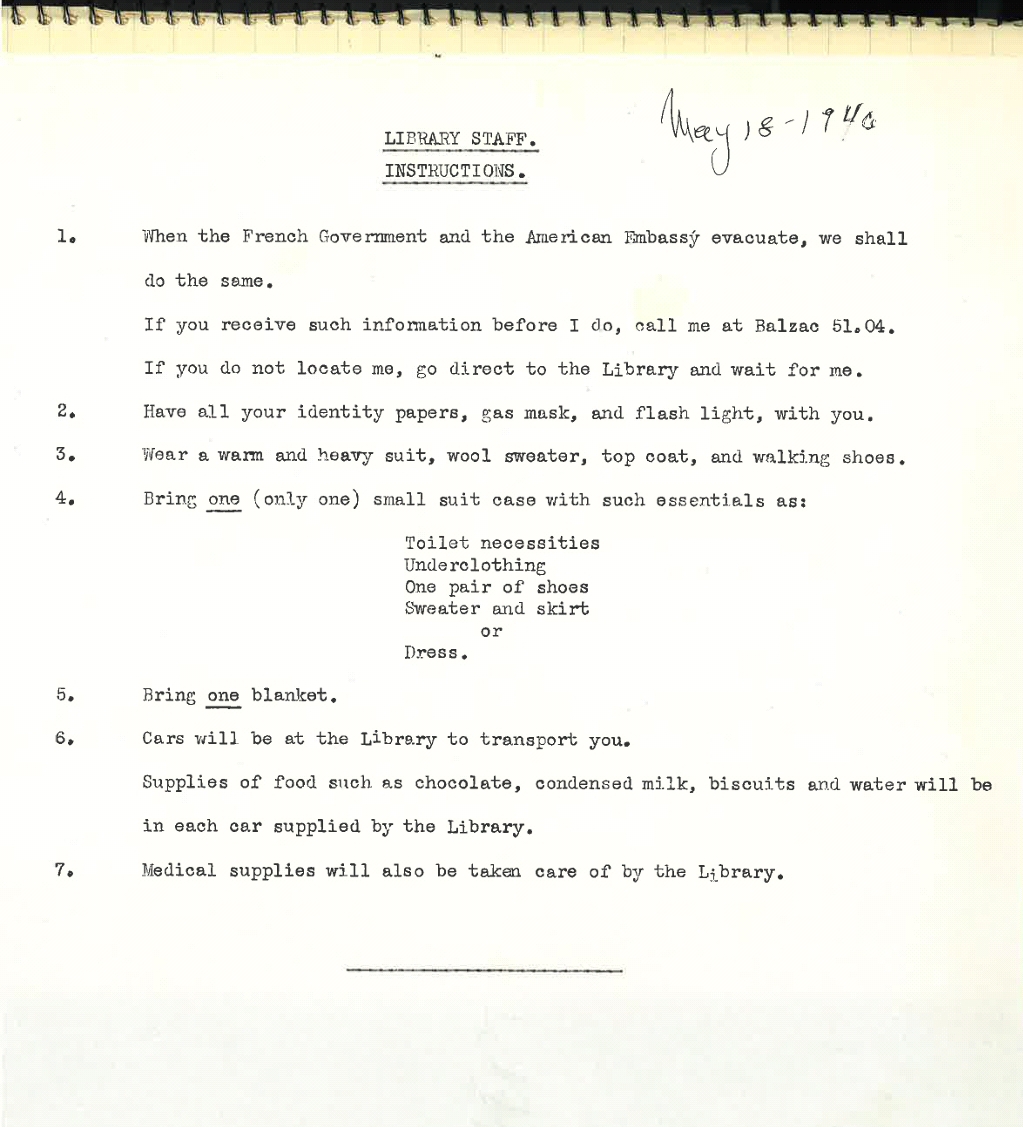

Moved by the stories of the past, I felt an immediate need to share with someone who loved the history of the Library as much as I did. Assistant Director Abigail Altman and I began exchanging documents. I learned that Dorothy Reeder had organized the Library of Congress stand at the Ibero-American Exposition in Seville in 1929. From there, she traveled to France alone and secured a job in the periodical section of the Library, working her way up to the role of Directress. In 1940, when the Nazis got close to Paris, most people fled, but she remained at her post. She sent her staff to safety in western France with these instructions:

Photo credit: the American Library in Paris archives

Photo credit: the American Library in Paris archives

I loved reading the Directress’s correspondence and included excerpts of her letters in the book. How can you not adore a person who puts chocolate at the top of their food supply list? When she returned to the States, she raised money and awareness for the Red Cross in Florida before training librarians in Bogotá, Colombia.

And what of the Bibliotheksschütz? I wrote to the Staatsbibliothek in Berlin and learned that before World War I had interrupted his studies, Dr. Fuchs was a student of theology. In 1925, he received his degree in library studies. After the war, he simply went on with his life, becoming the director of the university library of Mainz.

Photo credit: Staatsbibliothek zu Berlin

Photo credit: Staatsbibliothek zu Berlin

My onsite research continued at the Mémoriale de la Shoah in Paris. As opposed to the bunker-like BNF, the library in France’s Holocaust museum is homey, filled with thriving ferns in macrame plant hangers. The librarians are friendly and knowledgeable. Delving into their microfiche archives, I read dozens of letters denouncing neighbors, coworkers, and family members for everything from being Jewish to listening to the BBC to buying goods on the black market. Each day, on my way out the door, I passed a bulletin board filled with people’s inquiries. The one that haunts me is a handwritten card from a Jewish man asking for information about the Gentile family who hid him as a baby during the war. So many questions will never be answered.

At about that time, I started to receive responses to the batches of emails I’d sent about the people on which I based some of my novel’s characters. Kate Wells of the Providence Public Library shared an article about Helen Fickweiler, a New Englander who arrived in Paris three weeks before war broke out. The reference librarian fell in love with a shelver named Peter Oustinoff, and the couple worked at the ALP until Dorothy Reeder insisted that they return to the safety of the States. With very little to eat, Helen had lost 12 pounds by then. Once home, she was interviewed for the Evening Bulletin for an article whose headline read, “Back from Paris, She Hope Never to See Turnips Again.” She and Peter married. I had the great pleasure of corresponding with their daughter and granddaughter.

Research takes you from one place to another, from one person to another. When you read about World War II, every detail feels important. In French, when people say something is absorbing or demanding, they say, C’est prenant, literally, it’s taking. And you don’t know where the research will take you.

__________________________________

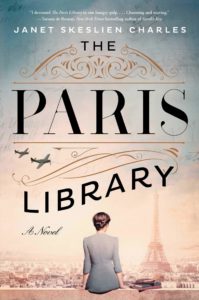

The Paris Library by Janet Skeslien Charles is now available through Atria Books.