Getting Inside the Mind of a Plagiarist

Kevin Young Goes Deep Into the World of American Hoaxes

Plagiarism is always aspirational. In a wish to have someone else take their place, or supply their words, plagiarists generally steal something better than they might write themselves. In this way, though it may seem an anxiety about status or a nervousness about originality, plagiarism paradoxically displays privilege—the belief that I could’ve thought of it if I’d had enough time or desire. This is one reason that while the hoax regularly refers to race, plagiarism is about class. But it isn’t the class warfare those few “in favor” of plagiarism declare, seeing it as a radical recapturing or conceptual collage. the plagiarist is no Robin Hood of words. Rather, plagiarism is the very definition of work without work. While hoaxers want to be someone else, plagiarists want someone else to be them.

In the novel How Opal Mehta Got Kissed, Got Wild, and Got a Life (2006), Kaavya Viswanathan details the aspirations of the main character, who seeks to get into Harvard, and by implication, realizes her own wish to become both a best-selling author and a polymath. A Harvard undergraduate herself, Viswanathan was marketed as many things in the run-up to the book’s publication, especially as a young overachiever who resembles her title character. Despite the character’s perfect scores and extracurriculars, when a Harvard interviewer asks Opal why she wants to go there and she cannot answer, he insists she pursue having fun or “getting a life” with the same kind of fervor with which she pursued perfection. Opal’s parents are also in on the project of making her more commercial, you could call it, with a schedule for getting busy in another sense, trading what they called HOWGIH (How Opal Will Get Into Harvard) for HOWGAL (How Opal Will Get A Life). Dating and television, the American dream.

The review copy I tracked down of Opal Mehta has an extraordinary amount of supporting material—advance press, publisher statements, reviews, and copies of glossy magazine features—that first accompanied the book and continued to accumulate in the few weeks it was on the shelves. Focused on Viswanathan’s backstory as a Harvard undergraduate—“The Six-Figure Sophomore” the Boston Globe would coo on 22 February 2006—the book’s press packet purposefully confuses the author photo and front cover, Viswanathan and Opal: “One is a sophomore at Harvard, and one will do just about anything to get in. Meet Kaavya Viswanathan. . . and Opal Mehta.” The sheer preponderance of evidence surrounding the book is actually reminiscent of the kinds of proof marshaled only after a plagiarist is discovered—usually listing the kinds of parallels between passages that ultimately indict the thief—not to mention the passages the plagiarist herself amasses, or the de rigueur excuses a plagiarist produces to say she isn’t one.

The book’s advance publicity had certainly helped, as Opal Mehta quickly climbed the bestseller list—unfortunately for Viswanathan, it was climbing right behind the latest of Megan McCafferty’s series of young adult books that began with Sloppy Firsts and Second Helpings. Within days after the book was published in April 2006, the Harvard Crimson revealed that Viswanathan had plagiarized several portions from McCafferty. Reaching for thirds, Viswanathan helped herself to both of McCafferty’s books to cook up her own. One similarity soon spread to a baker’s dozen of exact wordings, and less than a fortnight later, after previously featuring the author in a fluff piece, the New York Times reported, “The Crimson cited 13 instances in which Ms. Viswanathan’s book closely paralleled Ms. McCafferty’s work. But there are at least 29 passages that are strikingly similar.” All this gives new meaning to the question posed in the press release: “How far would you go for that one thing you’ve always wanted?”

Why, when they steal, do plagiarists take from popular material? Why not stick to the obscure? Or is it that we only catch those plagiarists who become popular themselves? Most plagiarism cases, as with other hoaxes, include what amount to clues planted almost expressly to be found. In the midst of the mounting accusations, Viswanathan went on the Today show where anchor Katie Couric subtly undermined the book, asking the tough but obvious question just weeks after it had gotten published. I remember watching that episode at the time, cringing. Bravo for Viswanathan for keeping what appears to be a previously scheduled appearance; she’s in full damage control, saying she’s sorry and that it was unintentional. When discovered, many do what Viswanathan did at first: plead subconscious stealing. (Don’t try this at your local Walmart.)

“The plagiarist is no Robin Hood of words. Rather, plagiarism is the very definition of work without work. While hoaxers want to be someone else, plagiarists want someone else to be them.”

This is the first defense of the plagiarist: I only did it once, and by accident. The second defense is plagiarized from the first: I only did it once. Yet as Mallon reminds us, “Plagiarism is something people may do for a variety of reasons but almost always something they do more than once.” The “unconscious stealing plea” goes hand in hand with the idea of only doing it once—not simply that I did it just that one time, but rather, in that one instance too, I was so unconscious as to be blameless.

To rewatch the episode now is to see the hoaxer plead innocence in a way familiar enough that it may seem plagiarized from some clichéd script. Indeed, all this was happening within months of James Frey, “Nasdijj,” and JT LeRoy implosions. Where the fake memoirist plays at suffering, the plagiarist, like the impostor, often performs innocence. In Viswanathan’s case this doesn’t mean just “not guilty” of the charges before her, but innocence as a permanent state—one feminine, youthful, American. Such enforced innocence—gendered and often raced—may explain why, in the press material of the young author, she is regularly referred to as a “starlet,” a term usually reserved for cinema. No matter her actual age, a starlet performs youthfulness—and matching beauty. Such youthfulness quickly if quietly signifies newness, freshness, and originality in turn, an approachable prodigy.

The early notices and prepress frame Viswanathan as a “girl wonder” a century after the iconic figure’s heyday. “A clever novel by a promising author. . . one of the hottest young talents in fiction,” says the Boston Globe. There’s a sense too of the author as somehow a new invention: the “young adult” (or YA as it’s known) Indian author; or more exactly, the Indian YA one. But by far the biggest suggestion of all is that the fictional Opal is true to life, a double who’s her and not-her. Opal Mehta is plagiarized from Viswanathan.

I don’t mean to substitute Freud’s couch for the Today show’s, yet we must be able to see the ways our culture’s cult of innocence and youth is also the culture of plagiarism. Newness at all costs yields pressure not just on the potential author but also on the culture that cannot be honest about its recycling, much less its trash.

The New York Times reported on 25 April, “In an e-mail message yesterday afternoon, Ms. Viswanathan, 19, said that in high school she had read the two books she is accused of borrowing from, “Sloppy Firsts” and “Second Helpings,” and that they ‘spoke to me in a way few other books did.’” The reports continues, quoting Viswanathan as saying, “Recently, I was very surprised and upset to learn that there are similarities between some passages in my novel, How Opal Mehta Got Kissed, Got Wild and Got a Life, and passages in these books.” The press release goes on to reiterate that any borrowing was “unintentional and unconscious.” I didn’t do it; Opal Mehta must have.

Is such a story believable on its poorly made-up face? How can Viswanathan recall and rewrite, word for word, a book she claimed to have forgotten she even read?

The first rule of influence is that there isn’t any. The second rule of influence is that it is everywhere. In the case of Opal Mehta, it wouldn’t matter for much longer which was which. For Viswanathan’s book—a phrase we can no longer use—turns out to have filched from a number of other authors, including fellow writers of Indian descent Salman Rushdie and Tanuja Desai Hidier, who published a novel titled Born Confused (2002), dubbed “the first book with a US female teen desi heroine.” Desi, to quote the contemporaneous, now-defunct website Sepia Mutiny, is “slang for the cultures of South Asia and the diaspora. It’s similar to homeboy, paesano or boricua. Etymology: deshi, Hindi/Urdu for ‘from the country,’ ‘from the motherland.’ Pronounced ‘they-see,’ it’s the opposite of pardesi, foreigner.” Opal Mehta’s publicity claims of being a new, original voice are not even true in terms of Desi culture.

While traditional print and television media was involved in the promotion and publicity of the book, as well as its downfall, its afterlife exists online alone. Online is also where Hidier writes of the case:

Ironically I first saw firsthand these sections of Born Confused on the day Ms. Viswanathan was quoted in the New York Times as saying: “I’ve never read a novel with an Indian-American protagonist. The plot points are reflections of my own experience. I’m an Indian-American.”. . . And so I was extremely surprised to find that the majority, though not all, of the passages in Opal Mehta taken from Born Confused are those dealing with descriptions of various aspects of South Asian culture (food, dress, locale, even memories of India, etc.) and the way that culture is expressed in America; essentially every scene of Opal Mehta that deals with any aspect of South Asian culture in more than passing detail has lifted something from Born Confused.

Hidier knows well that the marketing of both her book and Viswanathan’s is predicated on their being this supposedly unusual thing, an Indian writer; but where Hidier embraces it, Viswanathan denies it at the same time she pleads it. How could she copy what doesn’t exist?

The number of accusations increasing and evidence of plagiarism mounting, the publisher recalled the book, offering refunds. But why would Viswanathan not only plagiarize from, but also claim never to have read a book by fellow Desi authors, when her book is riddled with many of their exact words? The answer might be found in that Viswanathan could be telling the truth, inasmuch as she may not have exactly written Opal Mehta at all. Rather, the book may have been assembled by committee.

As the first feature in the New York Times mentions, Viswanathan got the offer to publish her book through a series of stand-ins and hirelings—the author’s admission to Harvard too was due not just to some parental plan but to a, how we say, “college packager”:

Her parents were not immune to the competitive pressure, however. Because they had never applied to an American educational institution, they hired Katherine Cohen, founder of IvyWise, a private counseling service, and author of Rock Hard Apps: How to Write the Killer College Application. At the time IvyWise charged $10,000 to $20,000 for two years of college preparation services, spread over a student’s junior and senior years.

But they did have limits. “I don’t think she did our platinum package, which is now over $30,000,” Ms. Cohen said of Ms. Viswanathan.

Ms. Cohen helped open doors other than Harvard’s. After reading some of Ms. Viswanathan’s writing (she had completed a several-hundred-page novel about Irish history while in high school, naturally), Ms. Cohen put her in touch with the William Morris Agency, which represents Ms. Cohen. Jennifer Rudolph Walsh, who is now Ms. Viswanathan’s agent, sold the novel that eventually became Opal to Little, Brown on the basis of four chapters and an outline as part of a two-book deal.

The deal for Opal Mehta was reportedly for half a million dollars.

We may forgive the New York Times for rehashing the story as Viswanathan’s was unraveling: “Ms. Walsh said that she put Ms. Viswanathan in touch with a book packaging company, 17th Street Productions (now Alloy Entertainment), but that the plot and writing of Opal were ‘1,000 percent hers.’” Beware of people who say “1,000 percent”—they might not know just when to quit.

All this does bring up the problem of authorship—who quote-unquote wrote Opal? Is the packager responsible, presumably, for just the kinds of press the author garnered or for shaping the story? And what percentage do they take? (Presumably less than 1,000.) The book packager’s very invisibility signals its power. “The relationships between Alloy and the publishers are so intertwined that the same editor, Claudia Gabel, is thanked on the acknowledgments page of both Ms. McCafferty’s books and Ms. Viswanathan’s.” seems one key way book packagers differ from the ghostwriter, that figure paid to have his or her work officially plagiarized. Alloy with its series like The Sisterhood of the Traveling Pants functions in exactly the opposite manner: the author as an idea divorced from the writing; the author as owner. This is actually behind the charge, and the practice, of plagiarism—the plagiarist is she who claims she owns, borrows, and expands to fit another’s words.

The book packager’s invisibility extends to the press packet for the book, authorless as the slang that peppers it. Rather than “about the author,” we are told “the 411” on Kaavya Viswanathan. A glossary defines it this way: “411 (n.)—information. Usage: I met this cute boy last night, but he left the party before I could get the 411 on him.” An interview with her is called “Gettin’ down with our flygirl,” with flygirl defined as “a really hip and sexy chick.” I’m not sure how outmoded 1980s slang terms like flygirl with origins in black, particularly hip-hop culture—other definitions listed include crunk and, more fittingly, wack—prove relevant, especially as written by corny publishing types. What was originally black slang now is seen as mere teenage talk. “Ms. Walsh, the agent, said: ‘Knowing what a fine person Kaavya is, I believe any similarities were unintentional. Teenagers tend to adopt each other’s language.’” Black talk: the ultimate ghostwriter.

Where Viswanathan is portrayed as exceptional in all senses, Opal sets out to become ordinary. What Opal Mehta, the book and the titular character, seeks is not to be beyond category but well within it. This is how class often works in America—her ambition is like my 11th-grade history teacher’s in Kansas, who’d repeat to the entire classroom the wishful assertion, “We’re all middle class here.” Though Opal is certainly upper crust in the book, and Viswanathan well paid and well raised, Opal conveys a wish to emulate the American bourgeoisie, to be as middlebrow as the book itself. Only in this way can she “get a life”—by stealing her way into one. Part of its aspiration is assimilation.

At the same time there isn’t any tradition that she knows of, Viswanathan says, promoting the idea that she is sui generis, without precedent. It is strange how Viswanathan wants to see herself as unique in her Indianness—is this another remnant of the book’s spin cycle, whether by a company or her? For Opal Mehta to live, Indian American literature—indeed, Indian literature in English—must die. In contrast to the hoaxer whose bio is enhanced, with plagiarism the writing gets enhanced to match the extravagant bio. Despite the cliché suggested by the book’s title, life of course is not something you get; you live it. When you’re not wasting it.

To plagiarize another is to steal a bit of that person’s soul—almost as much as soul music was stolen. It is also to steal, in other words, a culture. Whether we think plagiarism a crime—the only crime in literature to some—or at best a minor offense, all depends on if we’re the ones being plagiarized. Or on whether we see writing as work. But why would Viswanathan steal her own culture? Why plagiarize in spirit and image, if not words, exactly those things that India-born Viswanathan may have actually experienced? It’s a puzzle—she seems to do so for ease, of course, but also perhaps as a way of becoming American, claiming an Americanness that, the book’s plot seems to suggest, is always at a remove. There’s a sense that Opal Mehta is somehow living a plagiarized existence, trying to own what doesn’t belong to her: Harvard, full-blooded humanity, a “life.”

Opal Mehta must become a type for Viswanathan to live.

I have said plagiarism is about class, but it’s really race disguised as class. This is true of Viswanathan—not to mention Opal Mehta—who to some may come to represent the fast track that Harvard, or getting into it, has come to mean. When I was in school there, the saying went that the hardest thing about Harvard was getting in; if at all true then, getting in has become only tougher, with just over 2000 students accepted from a pool of more than 34,000 applicants for the class of 2016.

Such pressure is the focus of Conning Harvard, a book by an editor at the Harvard Crimson about Adam Wheeler, who conned, copied, and inflated his way into several of the nation’s nest schools. As Conning Harvard details, Wheeler started in 2005 with small but selective Bowdoin College, whose college application he completed almost entirely with plagiarized material; after two years, just as he was about to be exposed, he transferred to Harvard (while pretending to be transferring from MIT). At Harvard, he plagiarized papers and poems to obtain further grants and prizes. Only in 2009 did his bluff get called when he boldly applied for the prestigious Rhodes Scholarship to study at Oxford, and was on the verge of being named to the short list as well as being put up for the equally noteworthy Marshall Fellowship without having actually applied. A savvy professor recognized in Wheeler’s application his colleague and best-selling Shakespearean scholar Stephen Greenblatt’s work.

Wheeler had in essence a four-year span of plagiarizing—he presumably could’ve graduated from somewhere legitimately by then. After withdrawing from Harvard the next spring while the university decided his fate, Wheeler continued his wheeling and wheedling, applying everywhere from Yale to Stanford—and getting in the latter—with false résumés, forged documents, and more plagiarized essays. In May 2010, Wheeler was arrested and indicted on 20 counts, from larceny to identity theft. Wheeler’s is one of the few cases I know of plagiarism being prosecuted—he was considered, between grants, prizes, and financial aid, to have stiffed Harvard out of 45,000 dollars. (In contrast, Viswanathan would go on, like Stephen Glass did, to Georgetown University Law Center, which appears to have a fellowship for hoaxers.) If this is a drop in the bucket to Harvard, the richest university in the land, it might not be to another student whose place Wheeler was taking. His crimes go beyond plagiarism to include forgery of transcripts (a perfect SAT score, natch) and falsifying information such as his birthdate and his publishing record—in other words, outright fraud.

There’s always, in these cases of Ivy League pretenders such as Clark Rockefeller, more than a mere financial wish—rather, there’s a desire for the cultural capital such a school provides. Noted impostors like faker James Hogue, as detailed in David Samuels’s The Runner, actually earned good grades after getting into Princeton under false pretenses; his desire seemed to be both to run track and to run from his past. Julie Zauzmer’s Conning Harvard gives little insight into Wheeler’s motives, though it is well versed on his methods. This may stem from Wheeler’s being a cipher in that word’s contradictory senses (though not its “fly” hip-hop ones): he’s both without a center yet is a key essential to understanding our current culture of unaccountability. Not to mention cheating. His actions do seem particularly symbolic of the financial crash that was happening around this time, the kinds of bad mortgages and housing bubbles that made lenders and those who profited from them coconspirators at worse. Wheeler may be paying for all of our unoriginal sins—if so, 45 large sounds cheap.

After denying the charges at first, Wheeler eventually pled out; the judge gave him probation with the understanding that he never represent himself as having attended any of the schools he was kicked out of, but Wheeler continued to apply for things using a fake résumé, including for an internship at the New Republic of all places. If any résumé is a display of puffery, Wheeler’s is a remarkable dissertation on deceit: he claims to have been invited as an undergraduate to lecture at the National Association of Armenian Studies and to have given lectures at McGill University in Montreal titled “Cartography, Location, and Invention in The Tempest,” which never happened either. He claimed to be working on two more books with one already under review at Harvard University Press; he also declared he had four volumes “coauthored” with Marc Shell—an actual professor of his—forthcoming or under review. In reality these books Shell alone had written. Wheeler would not so much compare literature as conscript it to his purposes.

While all writers fall in love with different books and writers who influence them, few are faithful; great writers tend to go beyond a singular influence in that strange alchemy of many influences that creates originality. Plagiarists tend to be monogamous. They return to one or two texts to craft their plagiarisms. To get into Bowdoin, Wheeler plagiarized from a book of sample college essays compiled by Crimson editors that he would regularly return to; for his junior paper that won him a Hoopes Prize, Wheeler turned to a PhD thesis by a now-professor whose advanced ideas show up as if Wheeler’s own. Wheeler also regular used Rock Hard Apps—in an ironic twist, the very book written by the same woman hired by Viswanathan’s parents to help get her into Harvard.

If Wheeler was faithful to anything, or anyone, it was to Stephen Greenblatt. Wheeler had already won poetry contests undetected with a poem by Pulitzer Prize–winner Paul Muldoon (his terrific “Hay”)—there’s always a fake poem in there somewhere—and plagiarized Harvard professors like Helen Vendler and even Harvard’s president, Drew Faust. But again and again, he pillaged Greenblatt’s works—not his best-selling writings on Shakespeare but an in-house Harvard publication that proved Wheeler’s go-to bible.

Shakespeare of course regularly, almost religiously, borrowed— especially plots—but his example only reinforces the difficulty of invention and reinvention, the difference between an idea and its elegant expression. (Generally speaking, it is only exact expression, not any shared idea, that gets called plagiarism.) Yet despite his use of The Tempest in one claim, Wheeler doesn’t use his master’s voice to curse with—merely to accumulate honors. Why would Wheeler dare steal from the very writers he was trying to impress? Why not fish further from home? is question comes up quite often with plagiarists, who tend not to go far afield when they steal. One reason may be because plagiarists crave being known to those they know; another is that plagiarism, like the hoax more generally, preys on and pretends to intimacy.

If a thief, Shakespeare was a thief of the highest order—though the fact that a writer who took many of his cues from others managed to perfect the English language still produces great anxiety. This continued anxiety over Shakespeare’s quality can be traced to the 18th century, when Shakespeare’s name went from meaning just another good writer to the height of Western culture. This was also when the idea of originality as fundamental to literature took hold and was exactly when the West’s notion of plagiarism took its modern form. “Originality—not just innocence of plagiarism but the making of something really and truly new—set itself down as a cardinal literary virtue sometime in the middle of the 18th century and has never since gotten up,” Thomas Mallon writes. Yet despite its emphasis on originality and attribution, the 18th century was an age not just of rampant hoaxes but also of plagiarism; in fact, it is exactly because of such a newfound need for originality that plagiarism and other hoaxes proliferated, providing an anxious expression.

“While all writers fall in love with different books and writers who influence them, few are faithful; great writers tend to go beyond a singular influence in that strange alchemy of many influences that creates originality. Plagiarists tend to be monogamous. They return to one or two texts to craft their plagiarisms.”

Notorious William-Henry Ireland’s “discovery” in 1794 of Shakespeare manuscripts emblematizes and takes advantage of Shakespeare’s rediscovery by the 18th century as a whole—and the very kinds of anxious acquisition that would plague Wheeler. As his forgeries earned him not just acclaim but praise from an otherwise withholding father—he was literally named after another brother and feared he may not actually be his father’s son—Ireland ls continued forging ever more boldly, including a full-length play, Vortigern and Rowena, which he claimed to have found before having written a word of it. The play was only the latest discovery from a trunk like something clowns might climb out of, its unlikely trove including Shakespeare Folios; letters to Shakespeare’s wife, Anne Hathaway (one contained a lock of the poet’s hair); and “an early edition of Holinshed’s Chronicles, the historical tales from which Shakespeare had cribbed so many of his plots—this one with marginalia in the playwright’s own hand.” In other words, the very copy of the book Shakespeare would copy from. Though he publicly admitted his forgery in 1796 with a small pamphlet, An Authentic Account of the Shakspearean Manuscripts, Ireland had to state again and again that he had hoaxed alone—and that his father, who stood to financially benefit, wasn’t in on it. You can’t get more anxious about originality than having to prove even your hoaxes are your own.

Our time is no different—again. Our Age of Euphemism’s steady stream of plagiarism and increased attacks on Shakespeare’s origins—not to mention our desire to get near him, or to say he wasn’t who he said he was, with over 77 people posited as him since the 1850s—reflect another anxious era. Certainly the main through-line of the Shakespeare deniers, like other issues of plagiarism, centers on class. The thinking goes, how could Shakespeare not be learned in the most conventional sense? I reckon our Will must’ve been an Oxford man. All these debates about Shakespearean authorship, Shakespeare scholar and Harvard professor Marjorie Garber notes, are in many ways about ownership. Anxieties about Shakespeare’s identity always reflect larger questions of who we are. It is not so much that scholars find ciphers in the plays and poems; rather Shakespeare proves a cipher for those people, and eras, who question him. Garber takes particular glee in noting how many of these earlier suppositions about Shakespeare come from scholars from Harvard.

Just as he uses Shakespeare, Wheeler returns over and over to Harvard publications put out by the university or edited by the Crimson to reinforce his Harvardness—stealing Harvard in order to reflect it back. There’s this impostor syndrome found at Harvard that Wheeler taps into, through his writing and his case—a feeling of not being worthy of being there. I feel like a phony, like I’m the only one who got in accidentally, was an attitude I heard expressed more than once, the neat companion of Catcher in the Rye’s Holden Caulfield calling whatever and whomever he hates “phony.” It is a feeling familiar to modern life—one that plagiarism particularly embodies. The Elizabethans got the Bard; we get Adam Wheeler plagiarizing papers about him.

How to extend tradition and not be overwhelmed by it? How to belong though you feel you don’t? You can make the feeling of not belonging into a way of belonging; this is one definition of the writer. The plagiarist is more about belongings—about ownership and possession, which some euphemize isn’t theft. is euphemism provides one more of plagiarism’s clues and confessions.

Incredibly intimate, “plagiarism is a fraternal crime,” as Mallon notes; “writers can steal only from other writers.” Along with what Mallon calls “a death wish,” that notable, peculiar wish to be caught, plagiarists so want to belong to the company of other writers that they mistreat others’ work. Why else would Wheeler steal from professors on the very same campus he doesn’t quite share?

Within a year, Wheeler had violated parole and found himself sentenced to jail. There is little glee in the story really, though many have taken it a sign of Harvard’s own bubble, delighting in its going pop. But unlike in some other famous cases—like William Street, depicted in the cult film Chameleon Street, who conned his way into Yale and later pretended to be a doctor, apparently even performing open heart surgery successfully—Wheeler never did do the work.

Wheeler wasn’t just kicked out of Harvard; he was expunged. Anyone can get expelled, and any school can suspend you, but it takes real talent to get yourself expunged—this means not just being asked to leave or kept from graduating, but that the university destroys any record of the student having attended there. Such purges are rare enough that the only other one I know of is William Randolph Hearst, the model for Citizen Kane and the founder of yellow journalism. The reason: during exams, Hearst sent chamber pots to his professors with their names at the bottom; apparently not all were empty. His name only appears on campus at the Harvard Lampoon Building, where it’s etched in the stained glass he helped pay for. The gap between prank and hoax, yellow journalism and far yellower plagiarism, is slim but sure.

As today’s plagiarists reveal, the hoax has gone from Neverland to Hack Heaven, from flights of imagination and humor to a further version of hell. Dante’s Inferno would place frauds and liars in the second-to-lowest circle, with falsifiers in the lowest portion of that, forced to forever scratch their skin. A hoaxer’s skin is usually rather thin.

In the end, plagiarists and pilferers, “Opal Mehta” and Adam Wheeler and “Clark Rockefeller” don’t just steal another’s words or money or opportunities; they also steal experiences. (In contrast, professional ghostwriters who write college papers for a paper mill would seem to steal experience from the very people who paid the ghostwriters to have their experiences for them.) As Thomas Mallon puts it, “Anyone is relieved to come home and find that the burglar has taken the wallet and left the photo album. When a plagiarist enters the writer’s study it’s the latter—the stuff of ‘sentimental value’—that he’s after.” Both the subject and the strategy of plagiarism are sentimental, attached not just to the past but also to unearned emotion, which, rather than realize, the plagiarist copies verbatim.

The plagiarist would rather thank a stranger than cite one. The crime here is vast, and personal: Wheeler went so far as to copy another writer’s personal acknowledgments.

__________________________________

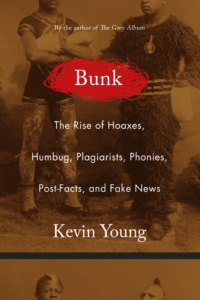

From Bunk: The Rise of Hoaxes, Humbug, Plagiarists, Phonies, Post-Facts, and Fake News. Courtesy of Graywolf Press. Copyright © 2018 by Kevin Young.

Kevin Young

Kevin Young is the Andrew W. Mellon Director of the Smithsonian’s National Museum of African American History and Culture. He previously served as the director of the Schomburg Center for Research in Black Culture. Young is the author of fourteen books of poetry and prose, including Brown; Blue Laws: Selected & Uncollected Poems 1995-2015, long-listed for the National Book Award; Book of Hours, winner of the Lenore Marshall Poetry Prize from the Academy of American Poets; Jelly Roll: a blues, a finalist for both the National Book Award and the Los Angeles Times Book Prize for Poetry; Bunk, a New York Times Notable Book, long-listed for the National Book Award and named on many “best of” lists for 2017; and The Grey Album, winner of the Graywolf Press Nonfiction Prize and the PEN Open Book Award, a New York Times Notable Book, and a finalist for the National Book Critics Circle Award for criticism. The poetry editor of The New Yorker, Young is the editor of nine other volumes, most recently the acclaimed anthology African American Poetry: 250 Years of Struggle & Song. He is a member of the American Academy of Arts and Sciences, the American Academy of Arts and Letters, and was named a Chancellor of the Academy of American Poets in 2020.