Getting By in Prison With Nothing But Books

Daniel Genis on Becoming a Citizen of the Incarcerated Nation

Three years after graduating from New York University, cum laude and a semester early, I passed through a pair of steel gates leading through the four-story bastion walls of Green Haven. About a decade later I was released into the parking lot of Fishkill Correctional Facility, where my parents waited for me along with five years of parole. In the time between becoming a state prisoner and returning to civilian status, I was housed in a dozen compounds and traveled the state to its northern border with Canada and its western edge at Buffalo. My grandparents died, and George W. Bush was replaced by Barack Obama.

When I look back, my extensive reading of the travelogues of 19th-century explorers was how I sought succor on my trip through the Incarcerated Nation. I read James Boswell’s Journey to the Hebrides with Samuel Johnson and Evelyn Waugh’s collected travel writing, as well as Paul Theroux, Ryszard Kapuściński, and other genteel travelers, but it was Richard Burton’s Pilgrimage to Mecca and Henry Stanley’s Through the Dark Continent with which I most identified. I had no Livingstone to presume, and the Royal Geographical Society did not sponsor my travels, but as I moved through the treacherous terrain of the state’s penal system, I took my own versions of notes on the varieties of human experience little known in the outside world.

I made sure not to forget who I was before I became prisoner 04A3328. This was a common theme in the literature of prison. Henri Charrière relied on his butterfly tattoo to survive the challenge in Papillon. Jean Valjean’s torment over becoming #24601 in Victor Hugo’s Les Misérables was clarified for me by my struggle to remain Daniel Genis and not the 3,328th prisoner to be processed into New York State prison in the year 2004. I had read Les Mis years before but returned to it for the description of its hero’s decades of confinement and escape. My first name was never uttered by the guards, not once during my entire bid. They called me Genis if they were being nice and Inmate 04A3328 if I was in trouble.

For our part, we were strictly forbidden from knowing anything beyond the first letter of their Christian names. This made for great fun when I accidentally learned that an irritating little bully’s name was David, as well as “CO Creep.” My friends and I would walk by him and say things like “The pictures of David online are going to get him fired,” or “She said David has a genital deformity,” leaving him visibly unsettled. In another case, a sexy and flirtatious young female correctional officer was only known to us as “E,” so we all proposed names suiting her. I thought I did well with my classical “Electra,” but it was my friend Billy Barovick who took the cake with “Erotica.” The rules regarding names seemed random, but the intention behind them was clear: replacing our names with numbers was deliberately dehumanizing, while secreting the correctional officers’ first names was an attempt to discourage fraternizing.

In any case I certainly tried to remain a free citizen of the world while the system put me through a conversion process I recognized from Primo Levi’s account of being processed into a death camp for Jews by the Nazis. The fact that much worse than I experienced was suffered by innocent people in The Drowned and the Saved made my flicker of self-pity laughable, but much of what I read in the books of the German and Russian camp life was familiar.

Downstate Correctional Facility was an hour north of New York. It was like the Sorting Hat in the Harry Potter books, though I guess we all went to Slytherin. Being the first prison that a convict sees, it had a processing procedure that was conducted with barked orders, insults, and even occasional violence; Elie Wiesel described something like it in Night, so I knew that such abuse was deliberate. Treating us badly right at the beginning of our confinement tested our attitudes toward this new and lower status in life. We were being checked for defiance.

I made sure not to forget who I was before I became prisoner 04A3328.This was a common theme in the literature of prison.

The clothing I had arrived in from Rikers was thrown out with fury and mocked as “gay-wear.” My orifices were rudely peered into, a part of the process supervised by a man wielding a club because so many failed to keep their cool when ordered to bend and spread. My legal papers, the only possession allowed to pass into the Incarcerated Nation from the various county jails from where we were each coming, were examined by a cop who made it clear it was disgusting for him to handle my effects. The hair on my head and face was shaved off by inmate barbers, and I was ordered to put lice-killing suds into my armpits and pubic hair, and then wash it off in freezing water. Refusing to apply the burning chemicals was another step that led to occasional outbreaks of violence, useful to the cops who needed examples to demonstrate their monopoly on it.

I attended to it all very carefully because I didn’t understand everything that was being said. Every first-time prisoner has to quickly pick up the jargon in order to function in the Incarcerated Nation. Coded into the specialized vocabulary of doing time are entire penological philosophies, as well as the countercultural venom of a population held against its will. There’s also racial and otherwise tribalistic tension, moral codes, and surprisingly much that is humorous. But the general gist is an attempt at professionalese in a world very far from professional.

Acronyms and abbreviations were common. CF means “correctional facility” and shows great optimism on Albany’s part. It’s a fairly new term and one that appeared as part of a cohort of fresh institutional language. The retirement of traditional terms like “warden,” “guard,” and even “prison” came as part of a wave of penal reform in reaction to the Attica prison riot of 1971, which some histories identify as marking the end of the 1960s. That event had prisoners of various minority groups joining together to demand an end to their disenfranchisement. Inmates protested, much as Black people, women, and gays had earlier done to demand an enhancement of their civil rights. Albany was charged to respond.

The symbolism was as far as most of the good intentions got; in essence, the changes were superficial. Doing away with the term “prison” did nothing for the recidivism rate. I always preferred the archaic, tough monikers like “clink,” “big house,” and “hoosegow” (from the Spanish juzgado [court], also the source of “jug”). Nevertheless, there was a specific vocabulary to learn, and no dictionary to brush up with in advance. You’d hear the guards say that someone got dragged to the “shoe,” and it turned out to mean SHU, or “special housing unit.” These are entire jails built for solitary confinement, though only in theory, because New York typically locked you in a room with another prisoner, often a maniac—a shoe à deux. If you had a lexicon, it would tell you that prisoners never used that term; it was always the “box” or the “bing” in common parlance.

CO, short for “correctional officer,” is neither a proper description of the men in blue nor what they are ordinarily called, unless it was to their faces, in which case they are always addressed with the title. Cops are also “hacks,” “turnkeys,” “guards,” or “pigs,” if one wishes to sound hard on the cheap. We prisoners were officially “inmates,” a term with pejorative connotations, while the out-of-fashion “convict” has today acquired a positive one.

Being a tribal society, we had flags. Our color was green; the coppers’ was blue, because of their uniforms. Things resonate; in my quest to read the longest of books, I turned to Edward Gibbon’s Decline and Fall of the Roman Empire, and then a few more works on things Byzantine. I was not completely surprised to learn that the factions tearing Constantinople apart during the long Byzantine twilight were aligned according to the blue and green chariot racing teams. Constantinople’s violent urban class war had blues versus greens, like us!

What one cannot help but learn about prison, should one find himself there, is that violence hovered over every transaction and interaction in an environment starved of resources.

What one cannot help but learn about prison, should one find himself there, is that violence hovered over every transaction and interaction in an environment starved of resources. Everyone stole whenever they could, and there was sabotage, too. I knew a man who would throw unopened cases of copy paper into the trash as his contribution to bringing down “the Man.”

The prison yard was also Adam Smith’s dream; while transactions between prisoners were technically forbidden, capitalism arose out of the bare earth as the men bought and sold from one another in a hive no less active than the trading floor of Manhattan’s Stock Exchange. The nature of our gray-market economy was made clear to me almost immediately, for while Newports and stamps may have been the official currency, addictions to gambling and drugs set the prices, and violence was the ultimate stock-in-trade.

Inside, the invisible hand of the market was naked and visible. In the Malthusian competition of all against everyone, the allegorical hand often functioned as a clenched fist. Dostoyevsky’s House of the Dead describes 19th century czarist prisons in a similar way. One can purchase so much in a prison yard. Packs of Newports will buy something to eat, various drugs, weapons, porn, and art, with carved bars of soap and photorealistic portraits being the most common. One can also acquire services like barbering, chiropractics, blow jobs, having someone stabbed, or having a love letter written. The latter was the only hustle I ever did much of, but every experienced prisoner had some way of making enough money for a joint or a meal.

The explorers whose works I studied also navigated a world defined by violence, even if tempered by wonder. Captain Sir Richard Francis Burton took a spear through both cheeks while penetrating the forbidden city of Harar in Somaliland, as I read in First Footsteps in East Africa: Or, an Exploration of Harar in the cheap Dover reprint, leaving him with devilish scars for the rest of his life.

One of the first observations I made about my fellow prisoners was that scars were common. Many bore thick keloid cicatrices from ear to mouth, known as “telephone” scars because of how and why and where they were usually acquired. Others had split lips or cuts extending down from the eyebrows to the cheeks, making “window curtains.” Also popular were “buck-80s,” denoting the 180 stitches required to close a full facial cut. One man even had a ragged tic-tac-toe game on his forehead. I managed to avoid facial scarring, but that’s not to say everyone I knew did.

Every prison also has a gambling operation or three, weekly sport tickets that cost a pack of Newports to play. Picking the right teams could pay off with 50 to 100 packs, and sometimes there were multiple winners. These were professional operations, run by men who had been bookies in the real world. Every ticket had a secret bank, where a stash of cigarettes was kept to pay winners and ensure that the rest of the populace kept playing. But because transactions between prisoners were technically illegal, there was room for the law to fatten itself.

A few weeks before my arrival at Green Haven there had been an atrocious incident. The victim was a crooked cop who had boiling oil splashed in his face. Like much violence in prison, this did not happen because of raging tempers, an inability to control vicious tendencies, sadism, or general antisocial sentiment. The attack occurred because someone acted outside protocol and caused financial repercussions.

With all the fripperies we buy and drape over ourselves to occlude or manipulate the expression of our true natures removed by the brutal limitations of prison, one is left bare to see and be seen.

Identifying where the bank for a sports gambling operation was kept was a coup for a crooked cop, who could legally confiscate anything over two cartons. He used paid snitches to find out which cell had the hundreds of packs of cigarettes and confiscated them, right into the trunk of his car. Such a big loss shut down the ticket operation, but even worse was that a precedent could be set. It was one thing for the convicts to have been caught misbehaving and made to pay the price; being intentionally targeted and robbed was another. Such a breach in the accepted code could not be allowed to pass, and as a result the officer was disfigured. Violence emerged for the final settlement of accounts.

The man who did it was serving life anyway. He got years in solitary for the attack, and the box time would hurt, but he would be taken care of by his fellow convicts during and after, and he expected to die inside. I suppose on the day it happened, part of the crooked cop did, too. I actually managed to read about the incident in a local newspaper. It reveled in describing the horrible damage done to human tissue by boiling oil but did not even try to determine why this had happened. The only reason offered was that the assailant was a prisoner and his victim was the law.

Years later, in a federally funded class meant to teach us how to solve problems without violence, I encountered the same pigheaded belief that violence was always the wrong solution. Prison taught me that the opposite was true; there were times when violence was the only one. Being rather meek-mannered in my life up to this point, I wished this wasn’t the case. But I was clever enough to know better. And I knew to be sure to pay my debts, lest I had to pay in blood. The violent life of prisons and their crushing limitations was mine for a decade. The tests and challenges and pain were a crucible for forging a better, harder man out of the boy who came in.

From that first incident on, violence often proved the theorems and derivations prison taught me. Mostly I learned about people, and if I include myself in that category, it’s all I learned. One can’t ask for a better subject, or for a better institution of learning. No wonder the Mob calls the joint “school.” But it is a place to learn about the naked self. With all the fripperies we buy and drape over ourselves to occlude or manipulate the expression of our true natures removed by the brutal limitations of prison, one is left bare to see and be seen. And the consequences of being a slow learner can include a ruptured colon, so there is every incentive to get things right. I had my books to learn from, and my human subjects. The books could cause anomie, solipsism, and paper cuts if used unwisely. The men cut deeper and aimed for the face.

__________________________________

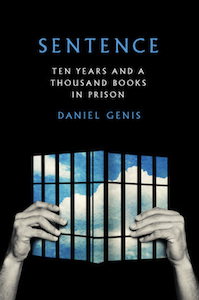

From SENTENCE by Daniel Genis, published by Viking, an imprint of Penguin Publishing Group, a division of Penguin Random House, LLC. Copyright © 2022 by Daniel Genis.

Daniel Genis

Daniel Genis was born in New York City and graduated from NYU with degrees in History and French. He has worked as a translator and has written for Newsweek, The Daily Beast, The Paris Review’s The Daily, The Washington Post, Vice, Suddeutche Zeitung, The Guardian, Deadspin and New York Daily News. His new book is Sentence.