Get Out, Claudia Rankine, and the Horror of Black Hypervisibility

On the Stag, the Sunken Place, and the Surveillance of Black Bodies

Horror impersonates the mundane. At its most efficient, it loiters in the center of life’s quotidian details, persuading residents that nothing dreadful has occurred in their world: A child’s body lies for hours in the road. A city slowly gentrifies. The word “slave” is written in neon, magnetic letters on a fridge—which did, in fact, happen at a nonprofit I worked for in Washington, D.C. last February. To most black people I know, none of this is a shocking affair. This is another Thursday.

I quit that job, eventually. But I have not escaped that day. It’s been a year. Racism, like any successful horror story, needs only the right amount of accomplices to hold one hostage. I do not believe my experience to be more or less unique than the routine degradation black people endure and have always endured in predominantly white spaces. And because of this, I felt kinship with two central images in Jordan Peele’s directorial debut, Get Out.

The film’s first horror begins with the death of a deer. This is a familiar slaughter: Society has made room to tolerate—and anticipate—roadkill. Yet Peele disturbs this incident through the impression it makes on the film’s protagonist, Chris. When Chris walks toward the forest from his girlfriend’s car, following the moans of the dying deer, his face is heavy with both paranoia and empathy. We too become perturbed, because the scene has now turned from the familiar. Chris looks so desperately at the deer because he does not see a deer. He sees a different familiar slaughter —that of his mother, who the film later reveals died alone on the side of the road in a hit-and-run when Chris was a child.

In this scene, trauma holds the black body hostage. Though at this stage of the film we do not yet know about the personal horror Chris harbors, we do sense the allusion to another everyday black terror. In the next scene, Chris is confronted by the policeman interviewing his white girlfriend, Rose, who was driving the car that killed the deer. Coupled like this, Peele offers two layers of black generational trauma: one that Chris marks on the deer, signifying his orphanage and familial past, and the other that we mark on Chris, signifying his vulnerability to the state and the law. In this moment, Chris begins to assume the role of the deer. He has officially become the hunted.

The dead deer also reveals Chris’ tragic flaw: his memory, which holds the guilt he carries for his late mother and her death (for which he cannot conceivably be deemed responsible). Rose, and her parents, Missy and Dean, later exploit this guilt to hold him captive. What’s more, Chris’s tragic flaw illustrates how the memory of collective black trauma is as integral to the horror genre as it is to the horror of white spaces. Claudia Rankine’s National Book Critics Circle award-winning book of poetry and criticism, Citizen: An American Lyric—confronts the myriad ways racism preys upon the black psyche. The collection opens with a reproduction of Kate Clark’s 2008 sculpture, Little Girl. In BOMB magazine, Rankine discussed why she used Clark’s image of a deer to open her book:

Clark uses taxidermy to create her sculptures. In the particular piece I used in Citizen, she attached the black girl’s face on this deer-like body — it says it’s an infant caribou in the caption — and I was transfixed by the memory that my historical body on this continent began as property no different from an animal. It was a thing hunted and the hunting continues on a certain level.

Kate Clark, Little Girl (2008)

Kate Clark, Little Girl (2008)

Throughout the collection of semi-autobiographical poems, Rankine revisits the deer as metaphor for the hunted and what the moan means for black people occupying microaggressive spaces that impale our humanity and citizenship:

To live through the days sometimes you moan like deer. Sometimes you sigh. The world says stop that. Another sigh. Another stop that . . . The sigh is the pathway to breath; it allows breathing. That’s just self-preservation. No one fabricates that. You sit down, you sigh. You stand up, you sigh. The sighing is a worrying exhale of an ache. You wouldn’t call it an illness; still it is not the iteration of a free being. What else to liken yourself to but an animal, the ruminant kind?

In Get Out, Chris’s guilt is used, by his girlfriend’s hypnotist mother Missy Armitage, to immobilize him, thus rendering him vulnerable enough to enter the Sunken Place. In the film’s depiction, the Sunken Place is a black, space-like void in which Chris can hear and see what happens before him as if on a television screen, but cannot move or alter the infinite descent of his mind from his body.

As a metaphor for the literal and cerebral captivity of black people in this country, Rankine locates her own version of the Sunken Place in the hypervisibility of the black body. Black people are not seen or allowed to operate as free agents but are rather subjected to constant surveillance so that they can be controlled. She writes in Citizen about an interaction with the police, “And you are not the guy and still you fit the description because there is only one guy who is always the guy fitting the description.”

To say it plain: free beings cannot sink. Chris, even before Get Out begins, is not free.

*

Peele recently tweeted about the definition of the Sunken Place, stating, “Because it’s a construct of the mind, everyone’s Sunken Place looks totally different.” I, like many black people who’ve seen Peele’s film, found within it a harrowing parallel to my own life. Watching Chris sink brought to mind my experiences with white people who have questioned my humanity because they suffer from their own self-inflicted feelings of inhumanity. At my former job, I felt this brand of exploitation every day after no investigation of the racist fridge message occurred; after I begged the administration to send an email and, bear minimum, address that the incident happened. The consequence of resisting apathy—which perhaps is another tool of the Sunken Place—was a heightened surveillance of my body: my labor was questioned and my feelings after the incident deemed full of paranoia and detrimental to my ability to succeed.

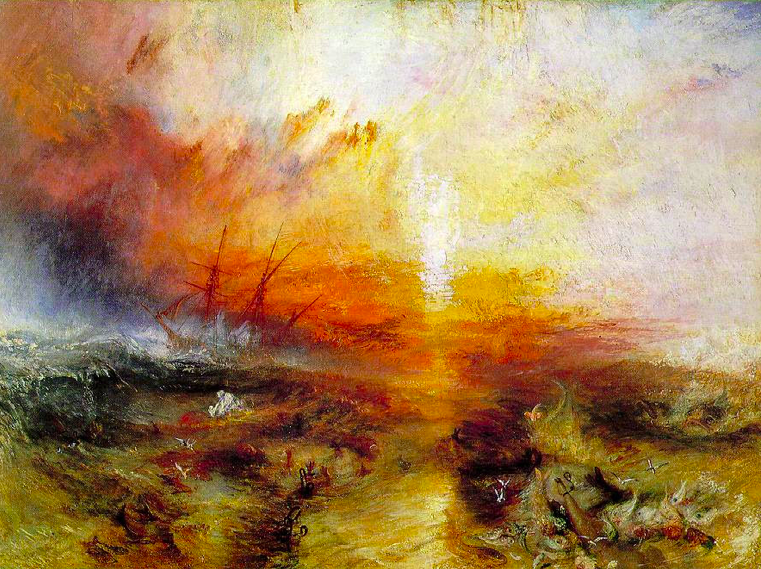

Peele also tweeted, “The Sunken Place means we’re marginalized. No matter how hard we scream, the system silences us.” I read that, and I imagined the funerals of the black trans women, whose names I only know as hashtags because they have been murdered. I imagined scenes from the Middle Passage: the final image in Rankine’s collection “The Slave Ship,” by Joseph Mallord William Turner, in which a foot juts out of the water while a body is torn apart by fish in the ocean.

J.M.W. Turner, The Slave Ship (1840)

J.M.W. Turner, The Slave Ship (1840)

But when considering the metaphor or Peele’s Sunken Place and its place in Rankine’s poetry, I am also forced to think about the living. The commentary in Citizen identifies sinking as a condition of black life:

For so long you thought the ambition of racist language was to denigrate and erase you as a person. After considering Butler’s remarks, you begin to understand yourself as rendered hypervisible in the face of such language acts. Language that feels hurtful is intended to exploit all the ways that you are present.

Get Out, dir. Jordan Peele (2017)

Get Out, dir. Jordan Peele (2017)

In Get Out, it is not the Armitages’ ultimate ambition to kill Chris, just as it’s not racism’s ultimate ambition to annihilate that which it desires to possess and control. Racism is also an economic system of oppression; it needs hostages in order to survive. The Sunken Place allows for Chris to be present enough that his body can still be exploited.

A few week before I left my old position, I had a sinking conversation with my former boss. She’d asked me to her office to discuss her disappointment that I had not shown any growth in my role. I had been there 10 months; this was the first time she’d noted anything negative about my performance. “I think you’re a smart girl,” she said. After a pause, she asked, “Do you think you’re a smart girl?” I nodded and my stomach lurched. We sat staring at one another for a moment. She sighed. “Well, prove it.”

*

Peele’s film ends the way it has to: having murdered her brother, father, and mother to escape the experimental surgery they have plotted to subject him to, Chris is chased from the Armitages’ home by his girlfriend, wielding a hunting rifle. His role as the stag has finally become literal. But miraculously, Chris is saved by two black men: Walter, the Armitages’ groundskeeper—who snaps out of his hypnosis in the Sunken Place to shoot Rose and then, chillingly, himself—and his friend Rodney, the film’s most reliable voice, who appears on the scene in a TSA cop car in a surprise twist.

When I saw the film, most people left the theater in relief and with some joy that, while Chris was injured, the familiar slaughter of police brutality did not occur this time for our black brother. But can we be sure Chris is still not a hostage? While he did escape his physical captors, what’s purposefully not made clear is whether or not Chris is really free from the Sunken Place, which only requires the sound of a spoon stirring against a glass to reinstate his captivity.

Of all the horrors in the film, this is the one I find most consistent with the indigestible nature of racism: how soft it can be at first, but then how everywhere, and perhaps, how permanent.