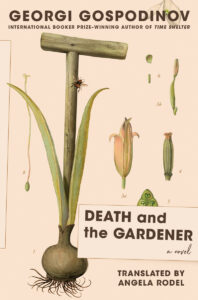

Georgi Gospodinov on the Loss of His Father and Writing About Death

The Author of Death and the Gardener in Conversation with His Translator, Angela Rodel

Georgi Gospodinov is one of Bulgaria’s most prolific authors. He is the recipient of the International Booker Prize, the Premio Strega, and the Jan Michalski Prize for Literature, among many other accolades. Here, he spoke with his translator Angela Rodel, who has won the International Booker Prize for translation and has received honors such as the PEN Translation Fund Grant and an NEA Literature Translation Fellowship, about death, translation, and loss.

*

Angela Rodel: You like to say that your latest book Death and the Gardener came as “emergency first-aid”—indeed this idea of stories as “first-aid” is woven throughout the narrative itself. What do you mean by this?

Georgi Gospodinov: Death and the Gardener was an absolutely unexpected book. My father was dying, we knew he had very little time left—the book describes how he would bargain with the doctors for a little more life. I brought him to my apartment in Sofia, and thus began our final month together of conversations and silences, of desperate maneuvers in the battle against pain. When he would drift off into fitful sleep, I would write his words down in my notebook, along with comments about the progression of his illness, the fentanyl patches for pain relief we were using.

I wanted to tell a story about the fading away of a life, about those final days when a person is still alive, about those last afternoons and nights, those final conversations.

When he passed six months later, I told myself I needed to write this book, no matter how difficult it might be. Because describing the death of a loved one means reliving that death. I wanted the book to be not just about death itself, not merely “death for death’s sake.” That’s nothing but a black hole, there’s no story there.

I wanted to tell a story about the fading away of a life, about those final days when a person is still alive, about those last afternoons and nights, those final conversations. I also wanted to retell the funny stories my father himself kept telling until the very last, “first-rate stories for emergency first aid.” And so this book was born.

And strangely—and sadly enough—it turned out to be first aid not just for me, but also for you…

AR: True. Our fates are clearly connected, for better and for worse. After sharing the Booker International Prize in 2023, we both experienced the loss of loved ones the following year. I remember you sent me Death and the Gardener in May 2024, I’d even started translating it when in July my husband Victor suddenly collapsed.

We rushed him to the hospital, and while waiting for the test results, I was fearing the worst, but telling myself “of course, it’s not cancer, I’m just awfulizing because of GG’s book.” But due to some sinister serendipity, it turned out to be Stage Four lung cancer, exactly like your father…

The next two months as my husband grew sicker and ultimately passed away were horrific, yet you and this book were a strange consolation to me, a “handbook” of sorts, written by a dear friend going through something similar, because terminal illness is actually a very isolating experience—people don’t know what to say or how to act.

So despite my own fear and grief, I knew what to do, thanks to this book: I needed to lie down next to him, hold him, hold his hand, and “show him to the door.”

Yet you were so open and vulnerable about all the emotions—hope, grief, helplessness, even the “magical thinking”—I was going through, too: for example, how you put on a brave face in front of the sick person, then go downstairs and sob on the street. You were also brutally honest about the physical mechanics of death itself, which our culture tends to mask and medicalize.

So one evening, thanks to your painfully detailed description of your father’s final moments, I realized Victor wasn’t just feeling awful from the chemo—he was actually dying. So despite my own fear and grief, I knew what to do, thanks to this book: I needed to lie down next to him, hold him, hold his hand, and “show him to the door,” that is, to simply try be a loving presence as I listened to his breathing grow slower and slower…

GG: While the book might have helped you as a reader, I imagine it was tough for you as a translator.

AR: Yeah, that’s putting it lightly. When I had to actually finish translating the rest of the book after my husband’s funeral, I definitely wasn’t calm or even present (I frankly don’t remember much of the translation process). But still, I’m thankful for it—translating this book forced me to face my grief and begin working through it. It would have been easy for me to get stuck in the shock of Victor’s totally unexpected death and keep going on autopilot.

Indeed, the great consolation I came to see while writing the book is that while death might take away the gardener and the writer, it can’t take away the garden or the story.

But this book gave me nowhere to hide. So while I was sobbing in front of my computer for most of the translation, I would try to do a chapter (which are mercifully quite short) a day—and this “titration of grief” as I translated your experience made it possible for me to begin processing my own loss. While the humor and beauty of your love for your father was also a consolation, reminding me to not let things I loved about Victor get overshadowed by grief.

GG: Indeed, the great consolation I came to see while writing the book is that while death might take away the gardener and the writer, it can’t take away the garden or the story. Time flows in a different way in a garden, it’s cyclical (which is also mythological) time, which incidentally is also the temporality of fiction. And all of that offers a certain salvation, a shelter of sorts from the unjustly brief and linear time we are given.

AR: Actually, now that I think about it, translation is also cyclical, a returning, rereading, reinterpreting of a text as the “season” of its reading changes. Which is why each generation needs its own translation of classic works, like a garden whose soil needs to be overturned now and then so it remains fertile…

But to step back from existential philosophizing for a moment, I think “Gardener” came not just as a surprise to you but also to your readers. This book about your father’s death is your first lengthy work after winning the Booker International. Usually, writing something new after a major prize is difficult. Not least because of all the traveling and events claiming your time, but also the inevitable psychological block that comes from that “raising of the bar,” that creation of new, higher expectations. Would you agree that against this backdrop, “Gardener” represents not only terrible personal grief but also a sort of creative salvation?

GG: Thankfully, my father was around to share the joy of the Booker. It was actually pretty funny, because journalists in Bulgaria somehow got a hold of his address in the godforsaken village where he lived and tended his garden. My father had never given an interview before in his life, so when they showed up he simply led the group of reporters around his garden and started telling them about the cherry and apply trees, about the tulips and tomatoes.

Now there, that’s my son’s favorite rose, he told them, pointing to a lovely, aromatic purple flower, which they dutifully lined up to sniff. His garden was truly magnificent. After he passed away, I honestly did not know what to do with all that sorrow, which filled up the niches of time freed up since I no longer had him to take care.

My father had two superpowers that saved him in the face of all those failures—his talent for telling stories and gardening.

So I hid myself away and simply wrote the book, using all my notes from that last month with my father. I finished the very last page precisely on May 6, St. George’s Day, a beloved family holiday that my father had hoped to live to see.

AR: I suppose we could see his passing far before that date as another “failure” of sorts. Throughout the book, you describe your father as the Don Quixote of failures—and yet, his ability to weave funny stories out of precisely those failures, also inspires another literary comparison: “that Scheherazade, my father.”

GG: My father had two superpowers that saved him in the face of all those failures—his talent for telling stories and gardening. He made a great story out of each of his fiascoes. Here I might add that he was the master storyteller in our extended family. He was indeed a Scheherazade, and when he started telling a tale, everybody fell silent, then burst out laughing, then went quiet again. Whatever I’ve learned about telling stories has come largely from him, from my grandmother and from Borges. Everyone in that lineage is important.

His garden, for its part, saved him during his first bout with cancer, which he beat, gaining seventeen more years of life even after the doctors had written him off. Actually, there are a lot of commonalities between gardening and storytelling. The loveliest is that both books and gardens continue to bear fruit years after the storyteller and the gardener are long gone.

AR: Yes, actually this is one of the things I love about this book—the novel very subtly portrays the catastrophe of a “private death” within a catastrophic world, in which death constantly deluges us from screens and headlines. In this sense, I feel Gardener’s theme actually resonates strongly with Time Shelter, as in that book, too, you examine the anxiety of societal-wide forgetting of the past, which leads to populism and its attendant political horrors through the very personal tragic prism of Alzheimer’s.

don’t believe in pure genres, we no longer live in single genres.

So in some sense, I suppose we should not be surprised that despite its superficial difference from Time Shelter, at the moment, Death and the Gardener is making an incredible splash in Spain and Turkey, in addition to very strong reviews in the UK. I’ve got my fingers crossed it will resonate in the US as well…

GG: The book’s reception in various languages has been truly incredible to me, every day I receive and read dozens of personal stories sent to me by readers moved by it. There are so many similar stories that have been locked away untold, to a certain extent this book has played the role of “key” for such stores. I hope this key also works in American locks…

AR: I suspect it will. It certainly did for me. But what would you say to publisher (and readers!) who are taken aback by or are dismissive of “Gardener,” complaining that “we expected a new Time Shelter” or some such thing? To say nothing about the thorny question of its genre—do Eastern European writers need to provide more explanations and justifications when using the technique of autofiction?

GG: Oof, you know how much I “love” that strict division of genres [laughs]. As Gaustine likes to say in “Physics of Sorrow,” genre is no Aryan. I don’t believe in pure genres, we no longer live in single genres. I also don’t believe the term “autofiction” is sufficient to describe the type of writing I am interested in. The book contains stories about my father’s generation, who were born at the end of World War II and lived through the second half of the twentieth century with quite a bit of hard-won dignity. Yet I am also interested in the “unhappened” moments in those lives. In “Gardener” there is also a short section about the absent father; from as early as the Odyssey to my own childhood, the father was always elsewhere and in some sense was the great lacuna in my own life.

__________________________________

Death and the Gardener by Georgi Gospodinov and translated by Angela Rodel is available from Liveright, an imprint of W.W. Norton and Company.

Angela Rodel

Angela Rodel is a literary translator who holds degrees from Yale and UCLA in linguistics and ethnomusicology. Eight Bulgarian novels in her translation have been published in the US and UK. She has received NEA and PEN translation grants, including an NEA grant for her translation of The Case of Cem. Her translation of Georgi Gospodinov’s Physics of Sorrow won the 2016 AATSEEL Prize for Literary Translation, and her translation of his novel Time Shelter won the 2023 International Booker Prize. A two-time Fulbright scholar, she now lives in Sofia, Bulgaria, where she serves as executive director of the Bulgarian-American Fulbright Commission.