George Saunders on Creating His Own Version of the Afterlife

Jane Ciabattari Talks to the Author of Vigil

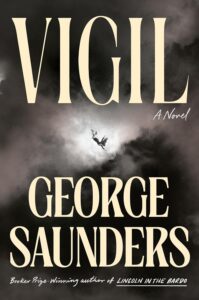

Those who are regular readers of George Saunders’ Story Club Substack were in for a treat on the tenth of December 2025 (a date chosen in honor of his story collection, a National Book Award finalist and Story Prize winner). That’s when Saunders offered the first public reading of his new novel, Vigil. He led off with this quick summary: “It’s the last night in the life of a kind of rotten guy, who’s been in the oil business, he’s one of these climate change deniers, and now he’s in his eighties, and he’s visited by a series of ghosts. His name is K.J. Boone. One of the ghosts is this kind of sweet young woman who died in her early twenties, back in the 1970s, and her name is Jill “Doll” Blaine. So the book is…a wild ass ride and it insanely overflows the banks to that description. But in the end, it became…for me anyway, kind of a reflection on, at the end of a life, does a person have the possibility of changing?”

Summary doesn’t begin to describe how his dazzling new novel amplifies Saunders’ literary genius, as he continues to reinvent the novel and the ways in which stories are told. Our email conversation took place during the darkest days just before the turn of the new year.

*

Jane Ciabattari: What a fascinating novel. I keep rereading Vigil. It may be creeping into my dreams.

George Saunders: Thank you, Jane—that is the perfect response, the one I aspire to get.

JC: When did you begin writing Vigil? What were the original seeds to the narrative?

GS: I started it, according to my notes, on July 4, 2023. The original notion was just the thought of all of these older people, mostly men, who spent so much of their time and energy in the late 1980s and 1990s denying the reality of climate change—via this big network of politicians and oil company execs and think-tanks and so on. At some point after the pandemic there was this period of almost comic weather going on—hurricanes, floods, fires—and I just imagined one of those denier-guys, watching all of that unfold on TV, and I wondered what he might feel—denial, guilt, both?

I think the stuff a writer has read and loved sits up in a sort of hopper above his head, informing everything—what he thinks a novel should do and how it should do it.

So: how does someone deal with the fact that he may have misspent his life?

JC: At what point did you settle on the title?

GS: I think it came to me almost right away—as soon as I decided to put it all on the night of that imagined guy’s death.

JC: Your opening is disorienting: “What a lovely home I found myself plummeting toward, acquiring, as I fell, arms, hands, legs, feet, all of which, as usual, became more substantial with each passing second.” Your point of view is a that of a ghost who has been sent to comfort a dying man. In these opening pages she sees herself in the beige skirt, pink blouse and black pumps her husband Lloyd picked for her to be buried in. She wears them still. Many decades post-death, she is “vast, unlimited in the range and delicacy of my voice, unrestrained in love, rapid in apprehension, skillful in motion, capable of traversing, within a few seconds’ time, a mile or ten thousand miles.” How did you develop her distinctive voice, with its echoes of Stanley, Indiana, where she was born and once lived as Jill “Doll” Blaine, married Lloyd, the man she loved, and died in an explosion in her twenties?

GS: Pretty much everything I do starts in improvisation, just trying different voices out, sometimes combining two voices into one. That was the case here. I had, originally, two different narrators, one who had died in 1880, another who’d died in 1976 and, at one point, just thought to combine them into one speaker. And then the question became: Why is this person talking like that, in those two distinct registers? And that person became…Jill “Doll” Blaine, the first-person narrator of the book—who is partly the person she was when she was alive in Indiana (sweet, working-class, very much in love) and partly someone more eternal, who speaks in a higher register.

JC: How did you come up with the concept of departed souls comforting the dying? What research was involved in writing this element of the novel?

GS: Honestly, she just blurted that out at one point. “I could comfort. I could.” And I liked the way that sounded, so I left it in. And suddenly you’ve got something like “plot”—as the book now tries to explain what she meant by that, and how she plans to go about it, and so on. That’s kind of how I work—trying to make the sentences sound good, compelling, authentic—and then taking note of what the character has said, and what that says about the fictive world.

JC: The vigil at the center of this novel is on the last night in the life of a crusty octogenarian, K.J. Boone, a self-made oil baron who has had a major role in denying climate change, accelerating the deterioration of the planet and the rise of a profit-centered culture much different from what Jill knew in 1976. “Greed, greed, one could taste it in the air,” she muses. She finds Boone “rude, abrupt, condescending, insulting.” Boone remains stubbornly convinced he is right, no regrets, no doubts. Which draws the attention of another ghost, a French man with a stack of papers documenting the man’s sins. What triggered your approach to this deathbed reckoning?

GS: Again, it all just sort of evolves as I improvise. This “improvisation” takes the form of just reading what I have of the book from the beginning and reacting in real-time to whatever’s there—it’s kind of like call-and-response. I sense what the reader might be wondering about, or what needs to be clarified, etc. The fun of this approach is it gets you into areas that your conscious, planning mind would never discover, and, as you go in there again and again, things start to get polished and developed.

It’s a hard method to really describe but it mostly involves many, many readings, and a resolve, each time, to poke at anything that seems iffy and add stuff playfully. It’s also very “sound”-based—I’m adjusting lines and adding words and phrases in each pass. And then, in the next pass—it’s a different world to react to.

There’s a weird kind of rigor that results from going through something that many times. It often feels like a better part of myself is getting expressed in the polished text than I ever see in, you know, real life.

JC: In your live reading from Vigil for The Story Club, you mentioned that the throughline of the book ties into fiction the group has read together—James Joyce’s “The Dead,” Katherine Anne Porter’s “The Jilting of Granny Weatherall,” Leo Tolstoy’s “The Death of Ivan Ilych,” and others—all of which explore “that essential question of whether a person who is stuck in the habits of his or her life can at the last minute pull of a Hail Mary and come to some kind of peace with their death.” In what ways have these literary works and others influenced Vigil?

GS: I think the stuff a writer has read and loved sits up in a sort of hopper above his head, informing everything—what he thinks a novel should do and how it should do it and all of that. There’s also a way that being aware of the precedents helps you navigate out into new territory. So, here, I had a hope of threading the needle between the precedential work—trying not to repeat what had already been done and thereby find a new thing for a dying and sort of rotten person to do there at the end.

So, for example, I knew that Scrooge experienced total reclamation. I was open to my guy doing that too, but was also watchful for ways that such a resolution might be, for him, false. So then the game became: getting to know him very well (through revising his sections over and over) so that, when the moment came, I’d know better what he might do (that might help my book build on that tradition of “last moment” books).

JC: I’m curious about your world building. At what point did you decide these ghosts could collaborate, even appear in groups, in crowds? And that they could move, quickly as needed (you use the term whisking), through walls, into the ground, into graves, across thousands of miles?

GS: There’s almost no “deciding” except on the spot, in the moment. (That is, very little pre-deciding.) So, the world gets built by way of the accretion of the “choices” made in the editing. For example, I’ll find I’ve blurted out a certain phrase that describes, let’s say, the way a ghost moves (whisks, in this case). If I like that sentence, and don’t want to lose it, so I resolve to leave it there, and, just like that, part of the world has been made (i.e., from now on, these beings can whisk). Then I have to honor that throughout. Or, sometimes, I’ll have two contradictory ideas, both of which I like, but then, eventually, I have to choose which is true. And that’s world-building/defining. Or sometimes, allowing both to be true can be a form of world-building. (If ghosts both whisk and fly….well, there you go…)

JC: In my Boston Globe review of Tenth of December, I wrote that you “capture the fragmented rhythms, disjointed sensory input, and wildly absurd realities of the 21st century experience like no other writer” and that you are “satiric without being sarcastic, ironic yet compassionate.” I also noted, “Like Kurt Vonnegut, you are morally acute and attuned to injustice.” Vigil seems to give you a wide canvas in which to explore that theme. Is that why you chose to a storyline that revolves around the possibility of “saving” Boone, an unrepentant character who revels in being “cock of the walk” and considers himself “more important than many (most) of the millions of souls who preceded him in death (“he’d had more actual power than most kings of old”)?

GS: Yes, for sure, and that’s a very perceptive question (and that was a very perceptive and generous review, thank you for it).

There’s always a moment when I’m first thinking of starting a story where I sort of scan for, let’s call it, import. “Is this going to be capable of mattering to someone?” If the answer is no—if it feels like the idea is merely clever or distracting or something like that—I’ve learned to maybe not do it. My hope is that anyone picking up this book, or any of my books, will eventually feel, “Ah, yes, this applies to me as well.” That way, whatever hi-jinks or experimental stuff or weird language I have to resort to will feel earned, if you see what I mean.

I think all of us need some “saving.” Boone is an exaggerated example of this but my guess is most people can find themselves in him, albeit muted. I saw myself in the way he works with denial—he keeps finding a new way, even in the face of new evidence, to keep himself in the right. That felt familiar to me.

JC: Your primary narrator, Jill, comes to a crossroads midway through the book. Frustrated at her charge’s insults, she whisks back to her hometown, to her own gravesite, and familiar spots. She witnesses how the place has changed. She confronts her feelings about the man who created the bomb that killed her. She is reminded what it was like to live in a body, as opposed to her elevated spectral self. These sections are loaded with remorse, questions about mortality and the afterlife. Even an experienced ghost can miss being alive. I found this section of the novel surprising, and of course moving. Where did it come from?

GS: Well, honestly, it came about because I was picking up on various clues she’d been leaving all along the way, especially in her voice—specifically, the fact that, whenever she went over to this wedding going on next-door, her voice would change—it would drop back into what I came to think of as “the Indiana register.” So that set up this pattern, which said something about her psychology: she is always working very hard to stay, as she puts it, “elevated,” so as to not be pulled back into this state of intense longing to have a body again.

But—none of that was planned. It was just nascent in the way she talked and then, through all that revising, I gradually became aware of it. And it’s interesting—once you become aware of it, it becomes a thing—one of the elements of the book that has to be tended to and developed. And that, in turn, becomes….well, I guess we’d call it plot.

Part of the writer’s job—well, maybe all of it—is to leave behind a text that inspires feeling and debate.

A lot of this involves watchfulness—noticing what the preferring mind (that is, the editing mind) as put in place, and accepting it, and building upon it.

A lot of my process, I think of as “priming the pump.” I doubt I’m using that phrase correctly, but what I mean is, I spend a lot of time with the first, say, 2/3 of the book, polishing and sniffing around for those sorts of hints, and the what I’m “priming for” is the last third of the book.

Another way of saying it: I’m like a juggler, trying to get some very specific bowling pins into the air, in a precise pattern, so that, in the last third, I can catch them.

JC: I’m wondering how you think about Vigil in relationship to your Booker Prize winning first novel, Lincoln in the Bardo. Both have settings that explore a liminal zone, themes that explore death, grief, loss, regret, so many more connections.

GS: I think Vigil is, in some ways, a better book—more compressed, and with a more difficult question at the core. The worlds in each are a little different. In Lincoln, one of the sources of tension was that the dead didn’t know they were dead—that was, for them, the big reveal. In Vigil, the dead know they’re dead but they retain that busy quality that humans have—they all have something they are very busy with, some task they feel they have to complete. I don’t think that, in Vigil, we necessarily know what the final disposition is meant to be for all of these souls. In Lincoln, it was clear (from the Reverend’s section) that there was going to be, for every one of these spirits, a final reckoning, somewhat along the Heaven vs. Hell line, and depending on the individual’s mind and psychological make-up. Here, because Jill has never seen that, we don’t get to know about it.

I think Vigil builds on Lincoln, or, maybe, asks a new question that grows out of the earlier book. The main question in Lincoln (I came to think, a few years after I wrote it) is something like, “What are we supposed to do, when we seem made to love, and yet everything we love is conditional?” In Vigil—well, it’s still pretty early in the “analyzing your own book” process, so I’m not sure. But I find myself wondering about who’s right, Jill or the Frenchman, in their view of Boone, and the book seems to want to say something about free will and compassion—can we (should we) be held accountable for our actions (good and bad) here on earth, when, in a certain way of seeing it, we were fully formed when we left the womb? (See book for details, ha ha.)

But if Lincoln says, “It’s hard to be alive, because everything goes away,” Vigil says something like, “Well, yes, but that feeling that things are ‘going away’ is all tied up in your attachment to self—what is going away, exactly, and from whom, really?”

But again—it’s early. Also, writing this book has made me realize that part of the writer’s job—well, maybe all of it—is to leave behind a text that inspires feeling and debate. But maybe he doesn’t need to weigh in on the debate. As Chekhov said, the artist doesn’t have to solve a problem, he just has to formulate it correctly.

JC: In comments after the National Book Awards ceremony in November, where you were honored with the Medal for Distinguished Contribution to American Letters (congratulations on that!), you mentioned the importance of revision. How did revision work for Vigil?

GS: As I mentioned above, for me, the whole process is about iterative revision—just going through the text two or three times a session, for month after month. If we could see it in fast-motion, the text would get gradually longer (with occasional radical cullings, so then it would get much shorter) and individual sections would appear, get polished, get cut and moved to the back of the text, get reinserted, then there’d be weeks or months of several sections being moved around within the document….and then, finally, certain sections would start to get locked in…so, for example, the first fifty pages might stay pretty much the same, with little tweaks still occurring now and then. Gradually, the “finished” portion gets longer and longer. But nothing is ever (ever) absolutely fixed until, at the very end, it starts to seem that, by changing things, I’m making it worse.

It is (as I can feel even as I reread the above, egads) an intense, anxiety-producing procedure, but….I’ve come to love it and I find that it makes me happy to do it, because, by now, I have a pretty high degree of confidence that, through this method, I can get a project to surprise me and to become more than I possibly could have imagined at the outset.

JC: What are you working on now/next?

GS: I have a few stories in progress but other than that, I’m enjoying a sort of post-book blank slate, waiting for something to show up and say, “Try me! I promise to be really difficult, but worth it.” At this point in my career, I am always looking for a project that will, at first, seem rich but also slightly impossible, because that’s how (I know) I might find an opportunity to stretch.

__________________________________

Vigil by George Saunders is available from Random House, a division of Penguin Random House, LLC.

Jane Ciabattari

Jane Ciabattari, author of the short story collection Stealing the Fire, is a former National Book Critics Circle president (and current NBCC vice president/events), and a member of the Writers Grotto. Her reviews, interviews and cultural criticism have appeared in NPR, BBC Culture, the New York Times Book Review, the Guardian, Bookforum, Paris Review, the Washington Post, Boston Globe, and the Los Angeles Times, among other publications.