Before the first genetic clone of Thomas Jefferson turned thirteen, he would puzzle out the steps that had led to his conception, beginning with his mother Marissa’s debt. To creditors the bipolar and unmedicated Marissa Barton owed fifty thousand dollars; to the drug dealers of Southwest Missouri, a smaller, more pressing sum. At Shoney’s she had been earning two-fifteen an hour plus tips. When she signed up for the crack-cocaine study, it was for the cash, and after blowing through that easy money Marissa didn’t balk at having her bills paid in return for submitting to a new kind of hysterectomy. Her daughters had moved out, her son was sixteen. If she wound up conceiving, said the researchers, she must carry to term or forfeit the payout. It made no sense, but Marissa was too strung out for questions and anyway, Bob, her boyfriend then, had had a vasectomy.

* * * *

From an early age, Marissa’s youngest child didn’t mind spending time alone while his mother partied. Carl Barton’s indoor pastimes—editing Wikipedia and drawing blueprints—were solitary ones. Compared to the mood elsewhere in his home, Carl enjoyed his bedroom and the quiet of his thoughts. He’d have explored the Ozark hills alone, too, but Silas Boyd Jr., the lisping boy across the road, trailed along chattering about Warcraft. It brought Silas no awe to discover an Osage arrowhead. If he mentioned school, it wasn’t to wonder about a science lesson but to prattle on about the polyester pants their science teacher wore. Carl didn’t care about pants. He edited encyclopedias. Lying beside Silas on the grassy hilltops, he would try to model the behavior of inquisitiveness, asking questions like, “Did you know these aren’t mountains, but an eroded plateau?”

“You’re an eroded plateau.”

“Have you been to the Rockies?”

“Do what?”

“You take vacations?”

“My mom’s a manager.”

“Mine’s a scientist.”

“She’s a crackhead.”

“She studies stars.”

“Want to get naked?”

“No,” Carl said. The wind on his naked skin might feel magnificent, but what he sought climbing Thistle Mountain was serenity. Gazing into a wild but consistent landscape dotted with fiery blooms, he lay still.

“Maybe next time.”

“Maybe,” Carl said, and indeed next week Silas asked again. Again Carl said no. The third time, Silas proposed a game: they would drop their pants and kick each other in the balls, and whoever took the most kicks would win.

“I played it with my cousin and I beat him.”

“Which means you lost.”

“You’re a dipshit,” said Silas, which was outrageous.

“Fine, I’ll do it, but with my clothes.”

“Well, I’m taking mine off.”

Silas let his pants fall. Proudly he stood there in briefs as Carl readied his leg and kicked, hard. The blow landed on target. Gripping himself, Silas lurched and leaned into the pain, trying not to wail.

It felt good to hurt someone as embarrassing as Silas. After a few moans, though, Silas stood upright again and grinned, which was when Carl fell forward into a fetal crouch of his own.

“You win,” he howled in mock pain, upside down while Silas’s pan-faced head moved closer. He shut his eyes. Was he okay? “I don’t know,” he whispered, wanting Silas to worry.

After a minute Carl opened his eyes to see Silas’s crotch bulging out through his briefs. His balls appeared twice their former size.

“Did that happen when you played with your cousin?” Carl said, pointing.

Silas reached down to feel. “I might should put some ice on it.”

They walked downhill. “Maybe a doctor, too,” said Silas on the trail.

“One word to your folks, and I’ll tell everyone.”

“It doesn’t hurt, it just chafes.”

“Your balls grow as you get older,” Carl said, more to reassure himself than to comfort Silas. “You’re probably just growing up.”

Back home, trying to edit, he kept losing himself in the same sentence on mountain formation. What was distracting him—his mother’s snores? She slept through plenty of afternoons. The bills? His brother Frank was paying those. The pain he’d caused? Thinking about that, he pulsed with dread. He felt like a sick pervert. Out the window he noticed that the Boyds’ car was gone. Where? The hospital. Why? His breath went shallow; he gulped down puke. Either Silas had told, or he’d succumbed before naming Carl. If the latter, the exam would show a bruise or there would be no exam. If the latter again, no one had seen the kick or someone had, everyone had, and so on until Carl heard on the TV news that, in a freak accident, a local boy had suffered testicular trauma, gone into shock, and passed away on a gurney in the ER.

* * * *

For days Carl waited for the cops to come for him and find his mother’s drugs and arrest her too. He could warn Marissa to lie low, hide the pipes, but how to justify his concern? Better her in prison than him coming clean. On the fourth day he attended the funeral, so awful that he retained few memories of it later on Thistle Mountain’s survey stone, eating wild berries until the knife-blade of dread chased him from his crime scene. A mother who paid attention might have connected Carl’s behavior to Silas’s death. One naïve question and Carl might have burst into blubbery tears, told all—it would have brought such relief—but the closest Marissa came was the day he found her on the couch, the curtains wide so any passerby could see her smoking.

“I’m studying Alberta,” she said, when he went to shut them.

“What’s Mrs. Boyd doing?”

“Gardening. Was Silas your best friend?”

“We knew each other.”

“You were always climbing hills.”

“I still climb hills.”

“It’s like, here I am, and Alberta’s got energy for flowers? I never taught you about death. I’ve had friends die, but I wasn’t young, I took you to that funeral and I . . .”

She trailed off. If she’d been clean, she might have felt in Carl’s vacant shoulder-pat how anxious he had become.

“I know what death is,” he said.

“Maybe sort of, but not really.”

“Spot and Rex died.”

“You remember Spot?”

“Mom, treat me like an adult?”

“Okay,” Marissa said. Had Carl obeyed the moment’s instinct, he’d have followed her gaze out to watch the Boyds’ house like a film with her. Instead he returned to his room and drew plans for a four-story shopping mall. Sketching its soaring atrium, he was able to breathe easily. As he laid out a zoned city around the mall, a belief crept in that he’d intended to kill Silas, so he threw himself into a more ambitious project, a megalopolis made up solely of limited-access highways. In 2000:1 scale the cloverleaves metastasized onto page after new page, crowding out thoughts. Evolution, taunted Carl’s mind in the distance, had paired Silas’s instinct for being hurt with his for hurting. He only drew. Like editing, the work was endless. If he heard a car at the Boyds’, he focused harder, and so on until August, when the principal began the welcome-back assembly with a moment of silence for their classmate who had tragically, et al.

* * * *

Weighing the rhyming sounds of silence and Silas, Carl went hollow. Each school day would begin with a similar call for “a moment of silence for meditation or personal belief,” and each day plainclothes cops would observe to see which kid froze up in guilt. Blueprints wouldn’t help. Nothing would but some all-out war. Fort Leonard Wood was up the road. If China nuked that base, killing everyone, one boy’s demise would come to seem a tiny thing. Their ballistic missiles had the range. Atomic holocaust, chanted Carl’s wanting mind as other kids coaxed meaning from their friend’s demise. “It’s when you touch yourself too much.” “It’s AIDS.” They seemed as excited as they were troubled. Nodding to agree that such a death could claim no honest victim, Carl wiped out his school with hydrogen bombs, conveying to God what he wanted now that he’d given up on his mother.

* * * *

In his first real memory, not a muddled glimpse but a sequence in time, Carl was four and Marissa was forty. They were eating popcorn on the carpet while reporters canoed through the Ninth Ward of New Orleans. He asked, “How far is that?” and Marissa replied, “Today? I need a place of peace. What’s it called, Carl, when you can concentrate? I’m losing focus, you’d do better with your sisters, they’d cook you food, at least,” and so on, patting his head to a peculiar rhythm. He asked no further questions. He was silenced by the thought that, even as he sat beside her, he might see his mother floating across the TV, face-down in the putrid waters spilling from Lake Pontchartrain. Lighting a pipe she’d never concealed from him, she said, “Don’t tell,” as if loyalty was something he still needed to learn. For years in his nightmares they’d been carting her off to jail. Those dreams stopped when Silas died.

Not that the death had coincided with an upturn in Marissa’s life. Lately she was getting messed up with a taxidermist named Willy. One October night while Willy and Marissa were out joyriding, Carl tried to conjure another of the old dreams to prove that he still loved her. Over and over he crashed cars on dark highways in his mind until he was envisioning his own transfer from juvenile to adult prison, where the guard warned the other inmates, “This one’s a sex offender.”

He woke up gasping. Maybe you could dread just one thing at a time, he thought, walking to the kitchen to find Willy and his mother listening to Led Zeppelin.

“Past your whatchamacallit,” said Marissa.

“Bedtime,” said Willy.

“That’s the ticket. We might go to the beach.”

“Mom, did you ever want to be a scientist?” Carl asked, wondering whom she meant by we, and what beach. The Gulf was hundreds of miles away.

“I wanted to be a nurse.”

“Cleaning up shit and vomit?” Willy said.

“Better than doing nothing all day,” said Marissa, her first statement in a while that made Carl feel like they had something in common.

“Tell me about Bob,” he said, naming his supposed father.

“Bob liked all those guys in the Highwaymen. Waylon and them. Born and raised in Texarkana and he drove an El Camino.”

“Was he smart?”

“Same as anyone.”

“Did he like science?”

“This is date night,” said Willy, shifting Carl’s mood. Frying fish sticks, he imagined again the fusion bombs falling, this time killing Marissa and Willy along with everybody else. He wished Marissa would clean up, climb mountains with him, enjoy the views, but it wasn’t meant to be, and he’d learned to be okay with that; if she wound up in prison, he wouldn’t go blubbering over it like he’d have done last year.

Carl dined in his bedroom with his blueprints laid out around him in a satisfying grid. Peering out at Willy’s trailing headlights, he saw a shooting star, and read up on meteor showers. Already a fellow editor had written about the unusually dazzling outburst of 9 October. Tonight.

The Boyds’ house loomed in shadow as he ventured into the chilly night. He lay down on the picnic table. Right away two meteors came dying across the sky. A boy who hadn’t killed his neighbor might have relaxed into pondering the dynamical evolution of meteoroid streams, but Carl zeroed in on something else, the wishes you made on stars. I wish never to be caught, he decided as another one flared. These burning rocks weren’t the bombs he’d asked for, but chances to remain free. I’m not a violent person, he whispered, as if that too was a wish. Don’t send me to jail.

After a dozen selfish wishes he thought of wishing for Marissa to go clean, but she was under the sky; she could make wishes of her own.

Amid frog croaks like low-pitched roosters he heard his name spoken, and sat upright to face Silas’s mom, Alberta Boyd, standing there in her Target shirt.

“It’s the Draconids,” he said, startled.

“You know, you look a lot like someone on TV.”

Even in the dark Carl could see that Mrs. Boyd, with her sharp cheekbones high on a narrow face, appeared years younger than his haggard mother, yet he knew from Silas that this woman was the older one. “You’ve known me all my life.”

“Not what I mean.”

“My mom’s away at the observatory.”

“Have you made a wish?”

“I don’t believe in that stuff,” he said, coming around to what Mrs. Boyd might mean: she’d seen him on America’s Most Wanted.

“Come talk to me sometime; I know your mom isn’t as available as you’d like,” she said, before walking away again.

More seething than afraid, Carl lay still in the dark. As a shooting star streaked toward a puny hill, he wondered if his father, too, had fallen politely quiet to mask rage. If he’d wished for nations’ ruin merely to calm himself at insults to his mother.

The phone rang inside. It was his brother Frank. “Making a run down to Topeka.”

“Mrs. Boyd was telling me I look like someone.”

“Like me and the rest of us,” Frank said, although they both knew Carl resembled none of the other Bartons. His chin was sharper, his eyes deeper, his voice reedier.

“Kansas is north.”

“I know where Kansas is.”

“You go up to it, not down.”

“Does Mom want her usual?”

“Did Bob have more kids?”

“Weird thing about Bob, he’d had a vasectomy.”

“So it can come undone?” Carl asked, feeling like he was learning that his whole life had been a dream.

“Mom was being evicted, is why I did my first deal. Except she had more cards than I could cover.”

Frank paused. Carl heard clicks of interference. Not just a dream, he thought, but some nightmare, where the terrible truth lurked invisibly around the bend.

“I found this place called Consumer Credit Counseling. Drove back home with the brochure, and Mom told me, I’ve paid my debts. Then nine months later. Anyway, her usual?”

Was Frank punking him? Was he strung out? A vasectomy reversal, the encyclopedia said, cost thousands of dollars. Marissa fretted over sums as small as twenty dollars. Maybe she’d blackmailed a rich guy. Carl went to her bedroom and pulled out a box from under her bed. It held disability applications, credit card statements listing hundred-dollar cash advances, and a crayon drawing of mother and son on a raft in the Ninth Ward, storm clouds swirling above. He tore it down the middle. Burn the box and the house too, he was thinking when he came upon a letter from a man named Jim Smith, at a place in Virginia called JCP, dated 2000.

Congratulations on your acceptance, it read. Peruse the guidelines, sign the confirmation and liability form, and return them before April 1. Upon receipt, our office will contact you about travel. If you have questions, call us at (703) 921-2258.

There were no guidelines, no letterhead, only this page whose number gave a busy-circuits signal when Carl called. He’d been born ten months after 1 April 2000. Pinching his arm, he tried to quell a sense that something demonic had occurred. A thin orange line glowed in the east. Civil twilight, he read, begins when the geo- metric center of the sun is six degrees below . . .

The phone rang. I’ve solved it, he thought, they’re calling to congratulate me.

“Ms. Barton?” said a woman.

“I’m Mr. Barton,” Carl said.

“Is Marissa Barton your wife?”

“Marissa is my mother.”

“Then give me your dad.”

“I’m searching for my dad.”

“Well, go find him,” said the voice, at which point it became clear this was the police, letting Carl know—as he intuited before he heard another word—that he wouldn’t be asking Marissa about the letter, now that she and Willy and two of their friends had driven off a cliff en route home from date night.

* * * *

There were so many kinds of bombs. Fission and fusion weapons, split into subcategories that ran to thousands of words each. Delivery systems, trajectory phases, navigational equations; still, some missiles lacked pages of their own. Across the wall from his grieving sisters Carl opened the Article Wizard to channel knowledge from schematic to encyclopedia. Hour by hour the templates grew. Propellant, warhead, blast yield, launch platform. There wasn’t some high heaven where Silas floated over to Marissa to whisper why he’d died; the dead quit knowing you, so he launched a new attack, not some vague bomb batch anymore but Dong Feng 31s and Julang-2s carrying payloads of ninety-kiloton MIRVs. From Jin-class submarines they flew toward America. The impact was cataclysmic. Instantaneously there was no crime scene, no Ozarks, no Bartons, only a lurching sensation like what he’d felt before the car wreck, a cold shiver, an extraneous coincidence, rather than the souls of the newly dead passing through him toward their starting place.

* * * *

The bungalow Carl’s brother Frank shared with his wife and their young sons sat on a four-lane bypass by a check-cashing store. There was a billboard tower in the front yard, and no internet except at the library in a nearby flat town. Once a week Carl could use his sister Sheila’s computer to look up Jim Smiths who led to various dead ends, but he couldn’t live with his sisters because of their jealous boyfriends. At his new school the top student, Wade Jones, had recently died in a wreck of his own. Since Carl was smart, the other kids pegged him as Wade’s replacement, conflating Wade’s and Marissa’s wrecks the way Carl conflated Wade and Silas. Every mention of Wade returned Carl to a familiar sick place. He began to worry also about the bad education he was receiving. In the work of some of his Wikipedia colleagues, he could perceive the gap between autodidacts and the classically educated. While his mind recalled numbers and diagrams well, and he saw beauty in symmetries both natural and syntactic, he knew next to nothing about the arts. He spoke one language. Rich kids on the coasts were vaulting hopelessly ahead while he lived on some highway. One Friday he sneaked out of school and biked across town to the Montessori academy to tell the director, “I’m Carl Barton. I want to enroll.”

“Your parents should come fill out an application.”

“My mom died, and I don’t have a dad. I live with my brother.”

The man’s tightening smile revealed the essence of what he would say: parental involvement was part of the pedagogy, and it wasn’t cheap; there were no scholarships. Rather than beg abjectly to mop floors, clean toilets, Carl thanked him and left. Riding home, he despised his sisters for attracting bullies, his brother for being a criminal, their mom for raising such a sorry lot. He delivered that anger into his pedal strokes. When he crossed the edge of a plateau into a rare descent, he was already soaring. Then it was like he’d leapt into another biome: sky crisp against a long prairie, exhilaration pumping out of his heart. His T-shirt an airfoil, he stood upright in perfectly dry air. The sky’s crispness, he thought, derives from aridity. When places looked pretty on TV, it was because they weren’t humid. For the first time since Silas had died, Carl felt hopeful. Screw the Ozarks. There were better mountains, and he could go climb them and ride down and his sorrow would be his own fault—that’s what he was thinking when his tire blew and he went tumbling over the guardrail.

* * * *

For a few months his hard luck multiplied. His blueprints disappeared out of his old house. A time-share developer bought Thistle Mountain and the hills around it. He learned that from his sister- in-law, Denise, as she fed and bathed him. Laid up all day with his broken legs propped up on the coffee table, he found that asking for help made him feel worthless and ashamed. Under his stinking casts his little cousins crawled, singing “London Bridge” while he sketched buildings and requested meals of minimal complexity, prepackaged things he hated the taste of, until one morning his brother and sister-in-law were arrested.

It was a lot like the old dreams: six cops busted in, handcuffed Frank and Denise, read charges of interstate drug trafficking, and carted them off. The social worker who stayed insulted Carl with children’s books and cartoons. Still, he continued to dismiss as magical thinking the notion that he had hurt the Bartons with his warheads, until the boyfriend of his sister Becky, who was preparing to take him in, stabbed Becky in the heart.

His sister Wilma wheeled him to Becky’s funeral, where his sister Sheila arrived with a black eye. “What’s with your eye?” asked Wilma afterward.

“It’s been a tricky week.”

“I’m on probation, so he can’t stay with me.”

“I can’t keep him myself.”

“Have you heard of Jim Smith?” Carl asked his sisters.

“I ain’t good with names,” Wilma said.

“Mom’s files say he admitted her to a program in Virginia.”

“That box went to the landfill.”

“Did she mention Jim Smith to you?”

“Did she talk to any of us about anything ever?” said Sheila, with a tinge of lament that made Carl sorry for her. Imagining the childhood they’d have shared if she’d been younger, he wanted to ask, Do you think we’ve endured an unlikely amount of suffering? She would only have answered that God gives no more than you can take. He kept mum. His hapless sisters seemed apart from him, logic problems to puzzle out rather than humans to love.

They moved Carl into Sheila’s apartment in the gaudy tourist town of Branson, next door to a country music theater where Sheila’s stalker worked at the bar. To take out a restraining order would get Glenn fired, so Sheila didn’t. “While I’m at work, don’t answer the phone or the door,” she said before leaving Carl alone to repair his reputation as an editor.

On her computer he abridged and amended page after page that he’d thought of as his to administer: the St. Francois Mountains; the Boston Mountains; the Salem and Springfield Plateaus. Together these made up the Ozarks, whose stems occupied Carl for days. The Ozark Mountain forest ecoregion; ecoregions in general; biomes; then back in toward the specific, updating citations, testing links. It wasn’t always intellectually valuable work, but it was satisfying, necessary work. Thousands of others were doing it at the same time. To imagine them all gardening their plots of knowledge together, fertilizing soil, plucking out weeds, gave Carl the well-being he used to find outdoors.

“Shouldn’t you go to school?” Sheila asked.

“Mom enrolled me online,” he lied. “The work’s electronic.” It was true he listened to Open Yale Courses while sifting through search results for all three-word combinations in his mother’s letter. Some work took place offline, like when he phoned the sperm banks of Virginia and every company called JCP, saying things like “I need to talk to Jim Smith,” and “This is Marissa Barton, calling about my account.” No one knew a thing. It seemed he would never learn why he stood apart from his relatives. By the time he happened to turn on the Late Show, on the evening of the day when one cast was removed and he graduated to crutches, he was ready to give up.

The guests, said the announcer, included a Marin County boy named Heath Nabors IV, “who, after comparing the DNA of humpback whales, songbirds, and humans, alleges to have isolated genes for musical ability.” That boy strolled onstage and the TV became a mirror. It was Carl’s doppelgänger, with his same oblong jaw, his fair face, his gangly arms, his questioning eyes, his age and stature.

Grinning in a way Carl had never seen himself grin, Heath Nabors IV sat down on a couch. “Your parents must be proud,” the host said.

“I’ve been emancipated from my parents,” Heath explained, with brash pride that sent Carl reeling into self-loathing even as he sat transfixed.

“At the age of eleven?”

“I’m twelve,” Heath said. Carl saw how he must have been sticking his own chest out. Giddy, he heard only little phrases of Heath’s. “Tonal metaphors.” “Acoustic exhaustion.” He imagined such a boastful voice booming out of himself while he kicked Silas, and here was how his lip must twist up in pride before bragging: “My dad made a deal. If I can play every instrument in the orchestra by sixteen, he’ll buy me a Ferrari.”

Heath produced a flute and whistled a display of his technical mastery. Whatever the fourth Heath Nabors had been emancipated from, the third was missing a boy, thought Carl as his sister Sheila entered the room.

“Has anyone knocked?”

“Does Heath Nabors IV ring a bell?”

“This kid? Is he famous?”

“Look at him,” Carl said. His twin was explaining his goal to decode whale speech; Heath doubted that birds had much to say.

“I saw this episode a while back,” Sheila said, as if to prove once and for all that Carl’s smarts derived from his paternal line.

“He resembles you a bit.”

She walked away. How could she not see it? Because of studio makeup, Carl thought. Because of schooling: i.e., money. Because of dread, the absence of it in Heath’s face, the presence of it in his own. A widening gap, already manifest. The adult Heath would be handsome like film stars, while Carl would be a worn and hard Ozark man.

A new kind of dread pooled like mercury under Carl’s skin as he glimpsed a life almost lived, an injustice so common to fairy tales.

He dialed long distance information to ask for Heath Nabors. Soon he was writing down the number for his identical wunderkind’s father. He held his breath and called it. When a woman answered, he asked for Heath the Fourth’s number. She gave it to Carl. He keyed it in. After two rings, he heard a click.

“Yep?” said his own impossible voice, and then Carl could have wept, because it was as if he’d tapped into some plane where Marissa was alive, where she had sought treatment, where she had put Carl in music camp instead of letting him wander to maim and kill.

“I saw you on TV just now and I’m—”

“Another one?” said his ostensible twin, without surprise.

“We’re identical. I can prove it.”

“No shit, moron. A musician recognizes the register of his own voice, even if you do sound like a hick.”

“What did you mean, ‘Another one?’”

“Do you love architecture and have a genius IQ?”

“Why; do you?”

“I asked you, shit-for-brains.”

“Have you been spying on me?”

“I’m sure we have cameras behind our eyes.”

Carl twisted the blinds shut, shuddering to think there could be film of his assault on Silas. “How’d you learn about me?”

“By answering the phone, numbskull. You’re the fourth to contact me. We’re all clones of Thomas Jefferson.”

In six keystrokes Carl had conjured an image of the man whose glinting eyes, high cheeks, and laconic smile could have belonged to an age-progressed image of himself. It seemed preposterous, and he knew that it must be true.

“Father of liberty,” added Heath, in case Carl hadn’t read that part of the encyclopedia.

“How’d you figure it out?”

“I’m a geneticist.”

“You’re twelve,” he said, even as he read that there’d been calls to exhume Jefferson and test his DNA for paternity of the Hemings children.

“At our age, the original Jefferson spoke Latin, Greek, and French.”

“Who else knows? Your folks?”

“Only the other four.”

“So they’re studying us from somewhere.”

“Didn’t I say so, dipshit?”

Carl was getting tired of being called stupid. Although he hadn’t injured Heath, or done anything in Heath’s presence to be ashamed of, he wished for the Tsar Bomba to detonate over Heath’s house.

“What did your folks do to you?”

“I guess you could say my folks loved me too much. But look, gotta go. Let’s talk tomorrow. There’ll be a Skype conference at noon.”

It was like Heath expected Carl to simply intuit how to find him online. And maybe, by virtue of his genes, Carl should be able to. If Heath was telling the truth, Carl should be able to command, to enslave, to speak with eloquence. Having cross-referenced the Jefferson page, he knew his abilities. He could foment revolutions. An orphan of radical inclinations, he recalled a quote from the man about refreshing liberty’s tree with the blood of patriots. Human blood, Jefferson had said, was liberty’s natural manure.

Carl relaxed into a sense of rightness. “Okay,” he said, “let’s talk then.”

“Well, that’s dumb of you,” said Heath, “since we haven’t even traded handles.”

To avoid notice as identical genius quadruplets, the clones had been using Heath’s blog as a private social network. “Try to catch up” was the last thing Heath said on the phone, and Carl spent an hour doing that, tracing his way through threads about language coaches, soccer camp, vacations abroad. Luc lived in Grosse Pointe, Talbot in Alexandria, Mason in Park Slope. Luc had had extra pages stapled into his passport. It grew tedious to read about the boys’ academic prowess, their overbearing fathers, the careers of their mothers. One mom was an Assistant Secretary of State, the others a producer, a renowned scholar, and a surgeon. Pondering what to tell them about the Bartons, Carl clenched up. It was wrong to feel ashamed of Marissa for being dead; still, however he felt about any subject, his clones stood a good chance of feeling the same. Astronomer, he practiced saying. Researched astrobiology. Lived in Biosphere 2.

He learned that Jefferson had loved botany and agriculture, philosophy and exploration, classical ratios, that his curiosity had been ardent about all subjects but geology. Carl had enjoyed learning about the Ozarks’ billion-year erosion. If I like geology, he thought, I’m an improvement on the original. To read the Virginia Statute for Religious Freedom gave him chills. It had gratified his shy, intense, soft-spoken, humble forebear to gaze beyond hills toward the vanishing point, as Carl did now in Branson, thinking, This is who I am. Perplexing though it was for the scientists to have given Carl to the Bartons, he thrilled to anticipate what was in store at noon. We’ll be farmed out to lead revolutions, he thought. No, they’ll put us through Harvard. We’ll be the founders of a Mars colony.

All night Carl read about the American Enlightenment. When the sun rose over Lake Taneycomo, he set his alarm for 11:30 and tried to sleep. Across the wall he could hear his sister quarreling with her boyfriend. The gist was that Sheila was a slutty whore and the boyfriend was done with her. “I love you,” she repeated as Carl imagined his sister alone, wrapping a Christmas present to herself after he abandoned her for his real family. Was he willing? What value to intelligence if it didn’t help his loved ones? Wasn’t it his job to make things better?

No, exhaustion was driving his mind to melodrama. The Bartons hadn’t bothered with Christmas in years.

When at last he slept, he dreamt his mother was a stock car driver with cancer, wired up to the transmission of her Chevrolet SS. She had to drive fast enough for the alkylating agents to be released. Her pedal was to the floor, but it wasn’t enough, and by the time the alarm sounded at 11:30 the cancer had spread to her brain.

He got up and ate cereal, reading the news. A Nobel laureate in economics had passed away. After he updated the man’s page with the date and cause of death, he clicked through the prior awardees, back to Frédéric Passy, French economist and first peace laureate. The man had been born in 1822, when Jefferson was seventy-nine. If Carl made note of the linkage, which existed only in the form of his thoughts, it would be deleted. To change Passy to Pussy, economist to dipshit, would get him exiled as a vandal. As if that mattered, he thought, feeling less and less like himself, until noon, when he clicked in to a video discussion in four little squares that each held his moving face.

“I’m Carl Barton,” he said, gulping down an impulse to run from this horror show of lookalikes with raised cheekbones, yellow-brown curls, and eyes of false beseeching kindness.

“No shit,” said the one with a cello propped up behind him. Heath.

“Say your name again,” said the boy in the lower right. “Carl Barton,” said Carl.

They all hooted with delight. “Do they have electricity where you live?” drawled one, in mimicry of an accent Carl had never noticed in himself.

“I’m on a computer,” he said, to more laughter.

“Where’d you grow up, on a train?”

“We moved around for my mom’s job,” he said, uneasy.

There was no parallel between the other boys’ mockery and the Jeffersonian qualities—politeness, curiosity, decorum—that he’d lain awake reading about.

“Did she drive a truck?”

“She studied the night sky.”

“In the Ozarks?”

“The Ozarks have night sky.”

“What did you score on the SAT?”

“I’m twelve.”

“So am I, but I faked an application to Harvard to see if I’d get in.”

“We have to attend different schools. Luc has dibs on Harvard, I’ve got Princeton, Talbot Yale, Mason Stanford.”

“So no one else knows?” Carl asked, but Heath was talking over him: “Hold your computer up and spin it around.”

“It’s a desktop computer.”

“Point it out your window. Is that the projects?”

“This is Branson. There’s no projects.”

“You know how science works; every experiment needs a control group and a white-trash welfare group. We hypothesized your existence weeks ago.”

Carl had always been different from the people around him, but not because of money. At his school most kids had been poor. He hadn’t felt ashamed. He tried laughing along with the others, and it seemed to work; the teasing bounced back toward Mason.

Mason had been caught making his dog suck his cock; now he had to go see a psychiatrist. Talbot guessed they were all genetically inclined to do the same. If so, the clones must have wished for bombs to fall on their cities, too. Heath, Talbot, Mason, Luc, or anyone would have kicked Silas to death.

Carl wanted to confess his apocalyptic fantasies, but the boys had shifted to wondering whether DHS had noticed their similar passport photos.

The debate, neither scientific nor analytical, bounced meaninglessly back and forth. Hadn’t; had; couldn’t have; must have. Even the speculation—“They’ll learn soon”—was perfunctory and incurious.

“Are any of you religious?” asked Carl, trying to think like a scientist.

“Duh, Ozarks, religious wackos don’t do in vitro.”

“If none of us are, it’s a noteworthy finding.”

“Read the blog,” said Luc, a reply Carl heard again every time he tried steering the talk away from matters of insignificance. The inanity of TV plots; the clones’ annoyance at camp humor. Though he agreed, he took no comfort in shared opinions on trivial matters, unless the others were hiding crimes like his and their curiosity was buried alongside their darkest shame. It was important to bide his time. If he said suddenly, “Last year I kicked a boy and he died,” he would be labeling them all potential killers. They might clam up, cast him out. So he only said “Me too” in response to shared taste after shared taste: elegant designs, anthemic rock chords, Tuscany. To be poor was to know less. “I loved it there,” he said.

After the call ended and the chat continued by IM, they bragged in foreign languages about their prowess in those languages. Carl used Google Translate to reply. Mason asked about his investment portfolio, and he culled an answer. It wasn’t just fear of being exposed in those lies that unnerved him when they scheduled another dialogue for that night. In some odd way he was beginning to feel proud of his family. No, he was troubled at a deeper level. He didn’t think the scientists could have deliberately ruined the Bartons’ lives, nor did he believe they could have peered into the boys’ future and pegged his as the most doomed. Still, it would have been nice to speak to inquisitive people about these ideas.

It had been too long since his last blueprint. He spent the afternoon drawing a federal center to house four coequal chambers of an imaginary government. When it began to resemble a honeycomb, he considered modeling the power structure on the colonial nests of bees. That didn’t suggest a way forward. The chambers, he decided, would be analogous to the human heart’s. A chamber to give oxygen, a chamber to take it back. A chamber to receive blood, a chamber to return it. White blood cells to fight off contagion, kidneys to remove waste, all controlled by the brain, and the honeycomb he revised into the Great Sphinx, jutting into the ocean on a craggy cape. When the government body was done, he hobbled down Branson’s gaudy main drag toward shapely green hills beyond. Another week and he would be hiking again. Did the others spend time outdoors? They skied and sailed, but if they yearned for wilderness, they hid it.

At the turn for Silver Dollar City, Carl considered visiting that old-timey park, finding out if its log flumes and gold-panning stations would awaken latent genetic memories, but he had no money. While Heath and company reaped the advantages of their geography and wealth, he couldn’t even enter Silver Dollar City.

Was his circumstance a maze to puzzle his way out of, he wondered, sulking onward? Was his bar set lower; must the others graduate summa cum laude from Oxford to match a middle-school dropout’s escape from the Ozarks?

The woman who spoke his name seemed to be hovering suddenly behind Carl’s head. He pivoted with his crutch to see an SUV driven by Silas’s mother, Alberta Boyd.

“Carl, is that really you?” said Mrs. Boyd, pulling onto the shoulder.

“What on earth did you do to your leg?”

“I was exploring.”

“Silas is at Randy Travis. I’ll give you a ride!”

Seized by eerie panic, he knew she must have deduced the truth—we all have cameras behind our eyes—but then he recalled that Silas had been a Junior, named for his father.

“Thank you, ma’am. I like to walk.”

“You must live with Sheila. Does she still sing?”

“She waitresses at a theater.”

“That’s nice.” He had never heard his sister sing. In silence he and Mrs. Boyd faced each other. Come talk to me, she’d said, with no idea what she was urging. He’d grown furious because it would have felt so good. Even now, light-headed, holding onto her side-view mirror, he nearly sobbed at the idea of it. Of admitting anything. The bombs, the crack, the other clones, the blueprints, so many secrets, amassing until a dam burst.

“I kicked Silas in the balls,” he said. “He died because of me.”

“That’s sweet of you,” said Mrs. Boyd without even blinking, “but it was his pervert cousin up in Tulsa.”

Over, he almost said. You went over to Tulsa, not up. “I’m not a pervert, but he asked me to do it and I did.”

“He admired you, Carl. You were a good friend.”

“At first I wouldn’t. I didn’t think I’d like it.”

“It was his cousin Rabbit. He’s in juvie now, up in Tulsa.”

Why wasn’t he glad? Would he feel this way forever? Trust me, he wanted to shout. He didn’t. Again she offered a ride. “Walking clears my head,” he said, refusing again, so Alberta Boyd drove off, leaving him alone with the old dread, fierce as ever, haunting him like a real ghost, and not even Marissa’s; where was her ghost? Hadn’t Carl done something bad to Marissa, too?

There were motels, family fun centers, a wax museum with a parking-lot carnival where he played midway games, tossing darts at balloons until he won a stuffed black bear that wore a toddler-size Branson T-shirt. Gateway to the Ozarks, it read. He wedged the bear in his armpit as a pad for his crutch. Back home, in wait for his pseudo-brothers to come online, he pulled up the Branson page. “Branson is a city in Stone and Taney Counties in the US state of Missouri,” it began.

Placing the cursor after the subject of that sentence, Carl added, “known as the Gateway to the Ozarks,” setting off the new text with commas since it was a nonessential clause.

He clicked through to his hometown’s page: a stub, in danger of deletion. He wrote about cash crops and commerce and linked to similar text in stubs about other Ozark towns. He was hoping to save them. There was still time. He edited mountains nearby, mountains in other states, other countries, even other worlds. With his atlas open to the moon he searched for peaks unnamed, as if he possessed any worthwhile knowledge of them. He gave Mons Moro a page. He gave a page to Mons Gruithuisen Delta. Like his description of Branson, they would be removed for lack of significance, but he denoted elevation and coordinates and name origins until the bell chimed.

“Hey,” he said when the other clones came onscreen, expectant, peaceful, mischievous, resourceful: four kinds of happiness to contrast his empty dread.

“Hey, you still sound like a hick,” Heath said.

“You’re still a fuckwad,” Carl said, and the others laughed in good spirits, seeming glad he’d joined in.

“I was reading about dialect discrimination. Apparently, it’s bigoted to make fun of hillbillies and hicks.”

They chuckled as if they knew what was coming. Even in his unease, Carl wondered if Heath’s upbringing stifled his innate polite humility, or had history failed to catch that Heath’s was the more natural Jeffersonian mode?

“What’s that say behind you?” asked Luc, of the stuffed bear.

“I won it at the fair.”

“Branson, then something smaller.”

“Gateway to the Ozarks.”

“You’re the gateway to the Ozarks,” said Heath, resurrecting Silas’s last living taunt: “You’re an eroded plateau.” The words echoed off Thistle Mountain and across the months and miles. To take the clones’ laughter to heart was ridiculous. Obviously Carl wasn’t an eroded plateau. By the joke’s mechanics, whatever he uttered was rendered absurd. Was it so absurd, though, to call a reborn Enlightenment naturalist who climbed hills and studied maps— who turned the local range’s name over in mind until it struck him as some ur-language’s first word—the gateway to those mountains?

They were still laughing. He had had enough. Every day he’d been soaking in shame, until he was wishing for the world’s end. Not just over Silas. His mother; his sisters; strangers’ pity at those wretched funerals. His petty edits to the encyclopedia—garnish, not knowledge—and on a mountain, when someone had asked did he want to undress in the hot wind, he’d said, “No.” If the geneticists were rooting for the underdog, they’d tensed up while he talked to Mrs. Boyd, and now they would clench their teeth again to hear Carl say, with no motive beyond catharsis, “I killed a boy last year.”

Immediately he had the clones’ attention. “There was no one else for miles,” he said. “It was a warm summer day, and Silas took off his clothes, because he wanted to play a game.”

Listening, each boy exhibited his own tic—Luc’s slanted smile; Heath’s twitching eyelid—but they were genetic equals, whose reactions must mean the same thing: they were all struggling to admit to wrongs on par with Carl’s crime.

Of course, he thought. Look who they were copied from! They had the DNA of a man who’d confined his boy slaves to a nailery under threat of the lash. Ones who fought were sold into the Deep South. Children as young as ten, living on a mountain at the edge of wilderness, but in a cage, hammering out ten thousand nails per day. Tranquility was the apotheosis, Jefferson had written. Freedom from worry; freedom from pain. Ataraxia and aponia: the Epicurean ideal. Would you spend your life harping on freedom from worry if you were free?

No, thought Carl, as he described tricking Silas out of kicking back, the terrible hike home, the news, the funeral, the aftermath. “Maybe that’s why I’ve learned no other languages,” he said.

Heath was typing. Another boy murmured. Carl waited for text to appear.

“Sounds like you needed that off your chest,” said Luc.

Or was it Mason, or Talbot? Both were suppressing the same smirk, as if no one else had anything to get off his chest. No words had arrived on Carl’s screen. “Look at the depraved things Jefferson did,” he said—an accusation, like saying, Look at the depraved things you’ve done. Look at the freakish secrets plaguing you! They wouldn’t look. Like their progenitor, they’d been raised too properly to defy the convention against reticence. That much was apparent to Carl now that he’d confessed. Not confessing had been miserable. Physical violence led to emotional violence, as it had done for the founders, so corroded by the guilt of enslaving that they’d dreamt of epochal ruin.

“No, you’re the depraved one,” Heath said. “Except for being genius polymaths, the rest of us are normal.”

“Maybe you’re right. Maybe my mom tainted my DNA when she smoked crack.”

He was beginning to hear the twang in his accent. He muted the speakers, not in spite. He had quit wishing for bombs to obliterate his twins’ cities. Suddenly the illogic of absolving himself by means of more harm seemed as obvious as his origins. Their lives were gaming out a wager whose odds had been set before Carl was born. Clone X to exceed historical Jefferson’s capabilities. Clone Y to prove capable of same as original. Clone Z to fail. If Heath and the rest kept up their tepid investigation, they would decipher a scheme to use settings of disparate privilege to pursue a trite inquiry into nurture and nature. Unplugging his modem, Carl forsook that quest for lack of significance. There were more intriguing questions. His injuries to the Hemings family alone had had Jefferson stoking the Reign of Terror. Whether or not that aligned with the record, Carl’s own thoughts proved it. He had worthwhile knowledge that would rewrite history. His dread was going to change the past. Not long ago, when he was still devoting his considerable brainpower to cluster-bombing, the ones who’d bet against him must have believed they were sitting pretty.

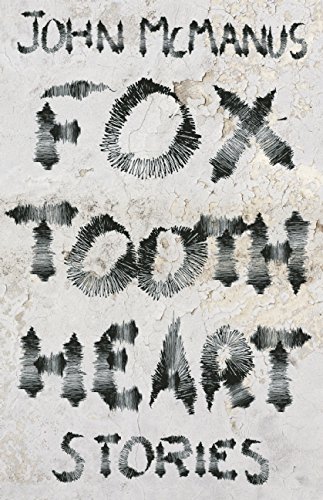

From FOX TOOTH HEART. Used with permission of Sarabande Books. Copyright © 2015 by John McManus.