Gary Panter, Matt Groening, and the Dual History of Punk and Comics

And the Outsider, DIY Ethic that Connects Them

Just about anyone who has paid any attention to pop culture in the past 30 years can picture Bart Simpson. He has popping saucer eyes, a red T-shirt, and what looks like a crown of jagged hair. First appearing on television in 1987, Bart is the perpetually-ten-year-old Simpson family son who quickly became a globally famous figure for pugnacity and rebellious disrespect (“Don’t have a cow, man!”). What few people know, though, is that Bart’s iconic hairline is lovingly lifted from cartoonist Gary Panter’s punk everyman character Jimbo and his spiky hair—meaning that one of America’s most beloved pop culture characters actually springs from a key figure in its groundbreaking punk scene.

In the late 1970s, The Simpsons creator Matt Groening and Gary Panter were both living in Los Angeles, in what Groening describes as “a couple of the sadder neighborhoods in Hollywood.” Groening, who graduated from the Evergreen State College in Washington, had grown up in Portland, Oregon, while Panter hailed from Sulphur Springs, Texas; both moved to LA after college. Panter was scrounging illustration jobs. Groening was working, among other places, at a copy shop.

At the shop, Groening self-published—that is to say, photocopied—his darkly funny Life in Hell, which he would staple together and send to his friends in the Pacific Northwest, including the cartoonist Lynda Barry. He also sold copies for a few dollars in the “punk” section of a local record store on Sunset, where he was an employee, called Licorice Pizza. The title—Life in Hell—was a reaction to living in LA. It featured anthropomorphic rabbits; its tone was existential and its star was the downcast Binky the bunny, also an everyman observer like Panter’s Jimbo. Binky, who has big ears, wide eyes, and a pronounced overbite, is joined in the strip by Sheba, his on-off girlfriend; Bongo, a one-eared rabbit even more alienated than Binky; and Akbar and Jeff, fez-wearing humans who are maybe brothers, maybe lovers. “Life in Hell actually sold copies,” Groening says. “Sometimes the punks would tear up copies, but sometimes I sold them.”

Panter, whose own self-published comics Groening had read and admired, wrote him a fan letter in 1978. (Leonard Koren, who published an avant-garde lifestyle magazine called Wet, first showed Panter Life in Hell.) Groening describes being actually “frightened” by Panter’s handwriting—today still known, which is to say admired, for its scratchiness and intensity—but he wrote back. The two met and became fast friends, plotting how to make art people would pay attention to. Groening recalls how they would “scrape coins out of the carpet of our crummy little apartments and split burgers and then scheme about how to invade pop culture.”

The two young cartoonists scraping to split some Astro Burgers between them would manage to succeed in that scheme. The Simpsons, Groening’s wildly successful animated television creation, is the longest-running scripted American prime time television show in history, and its insights and mottos have earned the status of cultural truth. “D’oh!,” clueless patriarch Homer Simpson’s exclamation, was added, in 2001, to the Oxford English Dictionary. Groening says he owes his success to Panter, who went on from their early, scheming days to win—among many other accomplishments—three Emmys as the set designer of the popular Pee-wee’s Playhouse, the children’s show and creative phenomenon that ran on CBS from 1986 to 1990. Remember the talking chair, Chairry, with her Betty Boop eyelashes and a mouth between the cushions? “He brought that psychedelic crazed Gary Panter style to Saturday morning, and completely warped a generation of kids,” Groening said in an interview with ForYourArt. “Gary went first, and he was my role model.”

The punk scene that launched cartoonists Panter and Groening was part of a larger punk movement that hit America, and the UK, in the mid-to-late 1970s. Both political and aesthetic, the punk movement, which often registered as a visceral or even violent response to mainstream pop culture, encouraged people to create their own culture across many different forms of production. This includes, most famously, the music that came to be known as punk rock.

Punk culture often consolidated around bands, particularly their live performances, and the independent labels that developed to put out their music, along with the art and graphic design that went into their promotion—as well as the fanzines that articulated their ideas and goals. The “do-it-yourself” ethic is the defining feature of punk culture and production. As Jaime Hernandez, the creator, along with his brother Gilbert, of the famed long-running series Love and Rockets explained, he never realized he could be a cartoonist until he got involved with punk. “Then I thought, ‘Oh, this is kind of the same thing,’” Hernandez told the novelist and comics writer Neil Gaiman. “They were all the same to me, so if you could do that with punk, you could do that with comics.”

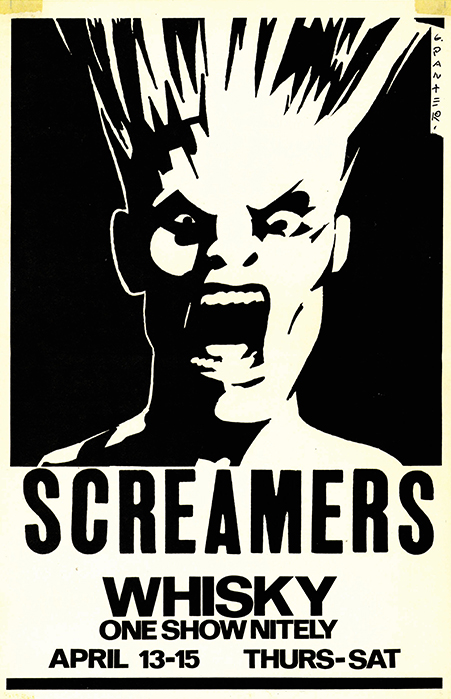

Screamers poster, art and design by Gary Panter, 1977.

Screamers poster, art and design by Gary Panter, 1977. Used by permission of Gary Panter.

“Punk” was a term for disrepute and outsiderness, resignified in the 1970s as an expressive, antiestablishment rejection of the “expert” and the corporate. The word “punk” had been used in the music magazine Creem to describe 1960s garage bands, and had appeared in gangster movies, in prison slang, and in Shakespeare’s plays (usually as a synonym for “whore,” as in “your French crown for your taffeta punk” in 1605’s All’s Well That Ends Well). It makes an appearance in William S. Burroughs’s 1953 Junky, in which the character Roy says, about two men harassing him, “Fucking punks think it’s a joke.” (Burroughs, in the oral history Please Kill Me, simply notes, “I always thought a punk was someone who took it up the ass.”) In mid-1970s New York, bands like the Ramones, Television, and Blondie—the latter name a reference to the eponymous comic strip that began in 1930—were generating zealous attention, playing at venues like the East Village’s CBGB. But it was only after the fanzine Punk began publication in January 1976 in New York that “punk” began to become a movement one could identify.

Before Punk, as Guy Lawley points out, people called the sound of these New York bands “street music.” “It wasn’t an original concept,” founding editor John Holmstrom, a cartoonist, explains, “but it wasn’t very well-defined, so starting a magazine called Punk took some nerve.” Soon after, more bands and fanzines that understood themselves as explicitly punk cropped up (and later Legs McNeil, another Punk contributor, complained that the world incorrectly understood punk as English). The Sex Pistols, a band from London whose one studio album, 1977’s Never Mind the Bollocks, Here’s the Sex Pistols, initiated a widespread UK punk movement characterized by short, sped-up rock songs and anti-conformism, gained transatlantic notoriety. In Los Angeles, where plenty of bands were sprouting up, the highly influential punk fanzine Slash—which also birthed an important record label of the same name—launched in 1977, the year Panter and Groening both moved to the city.

“Groening and Panter’s career trajectories demonstrate punk’s role in contemporary comics—and also how the graphic novel today trades on so many of its values.”

Fanzines link punk (a historical movement and ongoing system of values that prizes independence at the level of creation) and comics (an art form conventionally designed for print circulation) directly. Zines, as today they are commonly known, are independently published periodicals on a range of topics. The roots of zines and comics run deep together: teenage writer/artist team Jerry Siegel and Joe Shuster published the earliest incarnation of Superman in 1933 in their very own mimeographed fanzine Science Fiction: The Advance Guard of Future Civilization. And zines, with their DIY ethic, are a cornerstone of punk philosophy and its music specifically: they represent independence from the corporate, the building of community through the circulation and exchange of knowledge, and a forum for promoting bands. One sees in punk zines—as one does with iconic punk album covers like the Clash’s 1979 London Calling, a dark homage to Elvis Presley’s self-titled debut album combining pink and green stylized letters with black-and-white photography—just how key the frisson between words and images that motors comics is to the punk aesthetic.

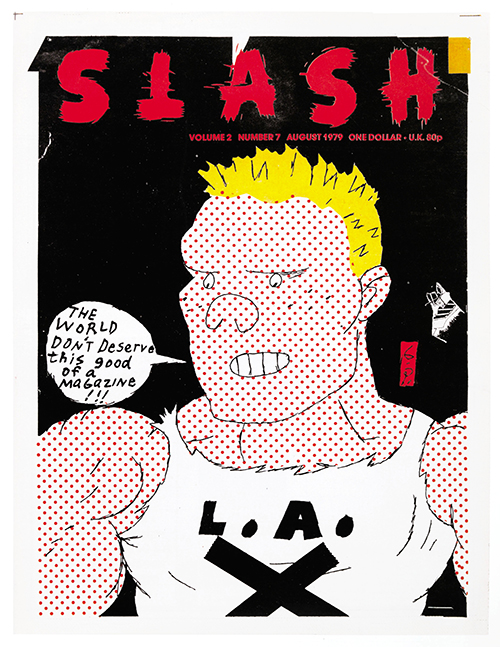

Groening and Panter’s career trajectories demonstrate punk’s role in contemporary comics—and also how the graphic novel today trades on so many of its values, including an emphasis on immediacy and the handmade, for what is now a mainstream audience. Alternative newspaper The LA Reader, founded in 1978, picked up Life in Hell as a weekly comic strip in 1980. Panter, who had also self-published, began publishing Jimbo, named after his signature character, once a month in Slash in 1978; he also created covers and design for the famed publication. Jimbo is an ageless navigator of a confusing world. Panter has said of Jimbo, who he has been drawing since 1974, “Jimbo is an observer. He is not very willful. His drives are simple. He is not stupid, but he is no genius. I use him to observe the places I put him in, which are satirical social, technological, and control situations.”

Gary Panter, cover for Slash featuring Jimbo, 1979.

Gary Panter, cover for Slash featuring Jimbo, 1979.Used by permission of Gary Panter.

Once they became friends, Panter and Groening, the two budding cartoonists, drew comics together in a wild, apparently untrained style for punk zines such as Flipside and Chemical Imbalance under the monikers the Fuk Boys or the Shit Generation. Their longest collaboration, “Ocurence at Oki Dog,” is an almost unreadably scribbled and dense two pages. One dopey looking character is rendered in a simple yet exaggerated style recognizable to any Simpsons fan and wears a T-shirt of LA punk band the Germs (Panter’s first wife Nicole Panter had been the band’s manager until they disbanded in 1980). The speech balloons are full of the cross-outs that characterize punk’s deliberately rough aesthetics. In the story, two friends set out in a car to hot-dog restaurant Oki-Dog, run over a pet cat, pick up a hitchhiker with a hook for a hand, and fight that hitchhiker before the car crashes and he dies on the street. While today one thinks of Groening as the creative force behind one of the biggest, most recognizable entertainment properties in history, Pulitzer Prize–winning cartoonist Art Spiegelman first knew Groening as “Gary’s punk rock friend.”

Panter describes that he was “kind of waiting for punk rock. I was waiting for someplace I could plug in.” He earned his BFA in painting at East Texas State University in 1974, and worked as a janitor in Texas before moving to LA, just around the time that punk rock was becoming a full-fledged movement. Panter recounted to Vice that one night shortly after arriving in LA, he was walking down Gower Gulch—the nickname for the intersection of Sunset and Gower in Hollywood—and saw a copy of the first issue of Slash laying on a newsstand. He found its sensibility similar to his—“big crude graphic stuff that’s probably out of fine art type of stuff, like [Robert] Rauschenberg and [Kurt] Schwitters.” Panter explains, “I’d seen something in the paper about punks, and I thought, these are like creepy little neo-Nazis, you know—what a bunch of jerks. But mostly it was people out of art school who wanted to make something happen.” In 1977, Panter created a poster that remains one of the most recognizable emblems of the punk movement: the stark, black-and-white graphic rendition of shrieking vocalist Tomata du Plenty of the Screamers. This dramatic image became the Screamers official logo and one of the most nationally and internationally famous images to emerge from punk rock. It alone adorns the cover of the recent art book Punk: An Aesthetic. Panter’s graphic sensibility came to substantially define the visual culture of punk, from band flyers, record sleeves and cover art, to T-shirts and posters, comics, books, and fanzines. Panter is the innovator of punk comics; people sometimes call him the king or the godfather of punk comics. In an interview in The Believer, Lynda Barry recalled Panter to me this way: “Gary was beyond ahead of the pack. I mean, you didn’t even know that you were in a race or on a racetrack or that you were a horse.”

__________________________________

From Why Comics?: From Underground to Everywhere. Used with permission of Harper. Copyright © 2017 by Hillary Chute.