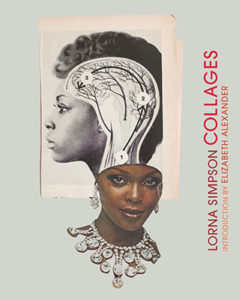

Galaxies Unto Themselves: Lorna Simpson's Collages of Black Women's Hair

"Black Women are the Shimmering Surface and the Power Beneath"

We start with the Book of Miss Brooks, and her poem, “The Anniad,” which casts the life of an “ordinary” black girl, Annie Allen, in epic scale and form:

THINK OF THAUMATURGIC LASS LOOKING IN HER LOOKING-GLASS AT THE UNEMBROIDERED BROWN; PRINTING BASTARD ROSES THERE; THEN EMOTIONALLY AWARE OF THE BLACK AND BOISTEROUS HAIR, TAMING ALL THAT ANGER DOWN.

![]()

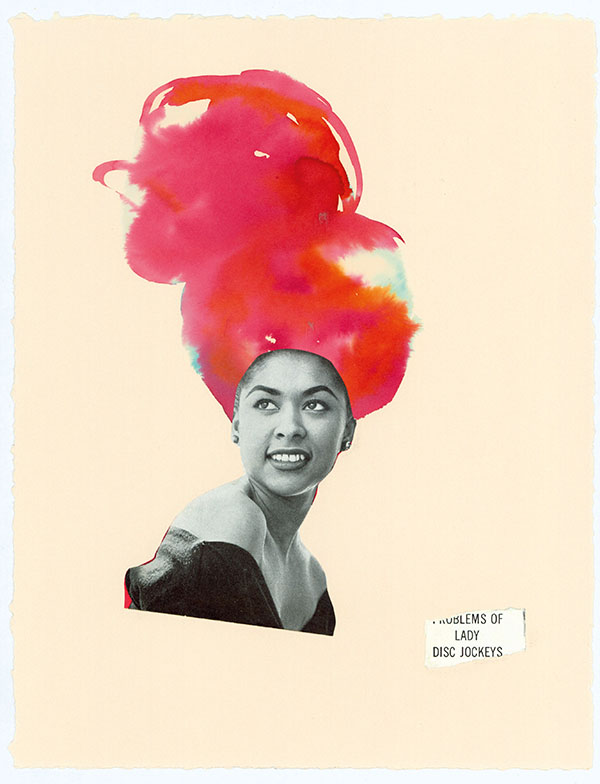

In Lorna Simpson’s collages, “the black and boisterous” hair is the universal governing principle. Black women’s heads of hair are galaxies unto themselves, solar systems, moonscapes, volcanic interiors. The hair she paints has a mind of its own. It is sinuous and cloudy and fully alive. It is forest and ocean, its own emotional weather. Black women’s hair is epistemology, but we cannot always discern its codes.

Lorna Simpson, Earth & Sky #17, 2016.

Lorna Simpson, Earth & Sky #17, 2016.

Watercolor is the perfect medium for Simpson here because of how it holds light and appears to be translucent. But it is also a wash, a shadow cast over what we cannot know in these women. Simpson’s portraits invite us to look, by their sidelong glances or direct gazes. We are compelled, always, by the phantasmagorical hair, which both invites and obscures.

In these pictures black women’s phantasmagorical hair is like smoke, but nothing is turning to ash. It is a non-consuming smoke, the mesmerizing beauty of smoke as it curls and wafts and draws a viewer inexorably near.

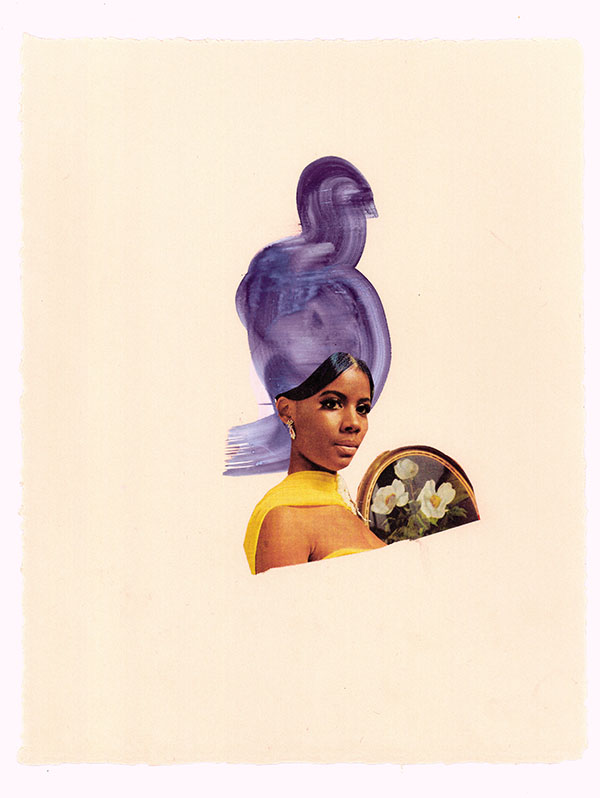

Lorna Simpson, Ultra Violet 2, 2015.

Lorna Simpson, Ultra Violet 2, 2015.

If black people are “the window and the breaking of the window,” as William Pope.L asserts (we are reminded by curator Amanda Hunt), what are black women, in Simpson’s vision here?

Black women are blue and black and ocher and goldenrod and magenta. Black women are unfathomable.

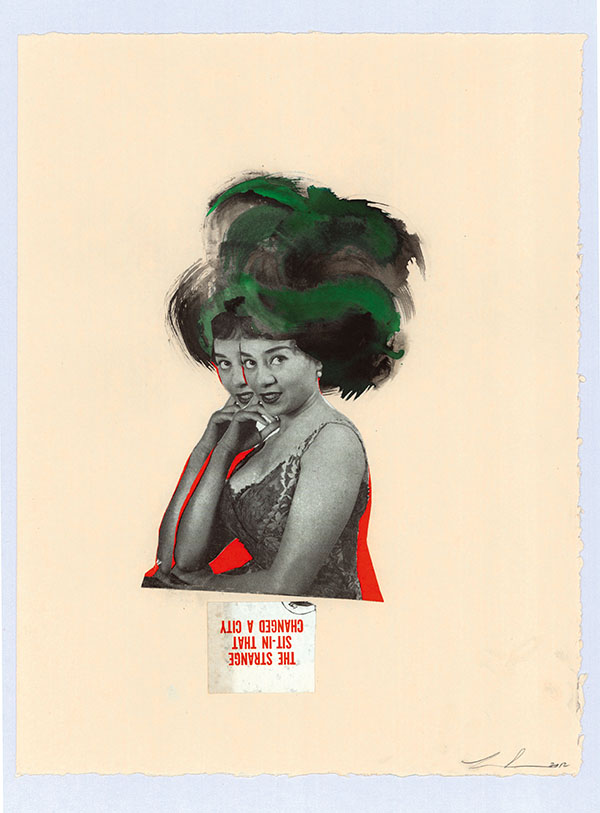

Lorna Simpson, Jet Problem, 2012.

Lorna Simpson, Jet Problem, 2012.

Black women are composed, necessarily immaculate. A black woman could go off at any moment.

Black women are mighty and terrifying.

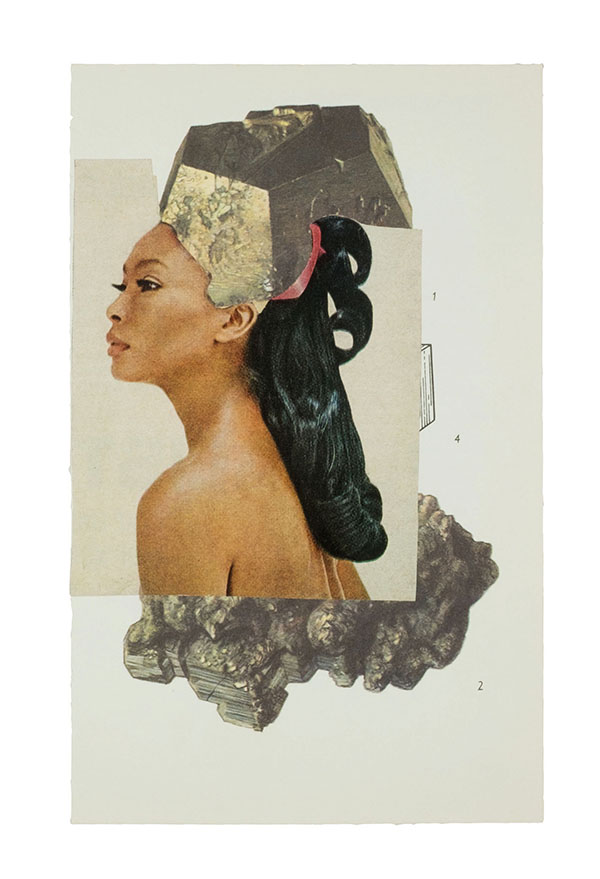

Lorna Simpson, White Roses, 2011.

Lorna Simpson, White Roses, 2011.

I do not know a black women who is at leisure. I have never known a black woman not efficient. Black women bide their time.

Black women are the shimmering surface and the power beneath.

What does it mean for a sister to sing that song?

The repetitions in these images suggest that we are thought of by some as a dime a dozen: undervalued, yes, but also, abundant. Black women are everywhere glorious and unsung.

Lorna Simpson, Jet Double Sit-In, 2012.

Lorna Simpson, Jet Double Sit-In, 2012.

The black woman is elemental, of the earth, magma, and gem, “malachite and azurite.”

She is Afro-blue.

Before the serpentine coil, the gravity-defying nimbus of black hair, there is grease and there are plaits and there are headrags and there are silk sleeping scarves and satin pillowcases. Simpson doesn’t show us that. Yet we know it is there.

Lorna Simpson, Unbroken, 2017.

Lorna Simpson, Unbroken, 2017.

One soundtrack to these pictures: A woman sings Otis Redding’s “Try a Little Tenderness” to her sister, her girlfriend. Black women, we sing to each other, a black woman artist singing an epic ode to black female beauty.

Ah black. Ah boisterous. Ah black. Ah beauty.

I want to name these women old-fashioned names: Viola, Simone, Mamie, Zora, Fern, Rachel, Daphne, Maudell, Thelma, Wenonah, Alondra, Farah. Adele, Matrice. Look, I’ve named some of them for women I love, whose eternal beauty never ceases to stir me.

Lorna Simpson, Earth & Sky #03, 2016.

Lorna Simpson, Earth & Sky #03, 2016.

Black women are the beginning and the end. Black women are the law. Black women are the ground and the sky, the horizon. Black women are the lucky number seven.

Black women are all the books in the Ancient Library of Alexandria, Egypt. Black women are Hammurabi’s code and the Rosetta stone: vexation and answer, secret and revelation.

Black women are surpassingly beautiful, and that is why you cannot stop looking at Lorna Simpson’s pictures.

The word “thaumaturgic” means: performing miracles.

![]()

From Lorna Simpson Collages. Used with permission of Chronicle Books. Art copyright © 2018 by Lorna Simpson. Introduction © copyright 2018 by Elizabeth Alexander.

Elizabeth Alexander

Elizabeth Alexander is a celebrated poet, essayist, and scholar. She is the author of more than a dozen books, including six volumes of poetry.