All the tables at the bar are full, as usual, but the staff, instead of waiting on the customers, is huddled in a corner; even the owner is there. I once heard his wife question the wisdom of that lack of interest in the clientele. “Where else are they going to go?” he said, without a trace of sarcasm, so she shrugged and went on talking with her friends. That’s when my notions about the ways of the world switched into reverse. It’s true. This is the only bar on the island.

I couldn’t join them because I was working the cash register that night. But I could hear them, talking about the afternoon’s waves. Most of the people who work here are surfers. The guy they called El Cojo, “The Crip,” was at La Lobería, the rest went to Ola Carola. From what I gathered, El Cojo had better luck, he caught the perfect wave, but nobody believed him. The staff tend to be skeptical, too many people pass through here and we ́re in the Galapagos. Everybody thinks they have the right to claim they saw a shark, they grabbed a dolphin by the fin, they swam with seven sea lions. Nobody believes them, everybody believes them. It cancels out. To a certain extent, it’s all a matter of perspective and ambition.

My colleagues don ́t stray from three points on the island: Playa Mann, La Lobería, and Ola Carola. The wildest thing you’re likely to see there is a German tourist lying topless on the beach. Life is too short to miss the perfect wave and those are the only places you’ll find one. Why go anywhere else? They know what they want and they go after it. I envy them. Once I read that the only way to be happy is to be satisfied with what you have. I work with a group of laid-back guys who only care about waves, that ́s why they ́re skeptical. I ́m not. I’m not a skeptic, but I ́m also not happy. I want, sometimes I don’t even know what I want. Eight years ago, right after arriving on San Cristóbal, I worked in the galley on a boat that sailed around the archipelago. Close to Wolf Island, with my head under water, wearing a face mask and a snorkel, I saw two mating stingrays more than six feet long, seven humpbacked whales, and hundreds of sharks swimming ninety feet below me.

I like to listen and I tend to keep quiet, or at least I try to. But sometimes I can’t, sometimes I talk too much.

“That’s Robinson Crusoe’s map,” I say. The man turns and looks over his shoulder.

“What?” he yells.

“That’s the map Alexander Selkirk made of the archipelago.” I walk over to his table and put my hand on the map he’s spread out. He widens his eyes and stretches his neck, he’s got some kind of a gadget behind his ear, he looks like a turtle, his skin sags in folds as he leans over the tablecloth, there’s a cataract on his right eye. He looks at me, searchingly, he wants me to keep talking, a sign I’ve already said too much. I ask if he wants another drink. He shakes his head, points to the chair next to him. I sit. This guy didn’t come on a tour. If he had, the bus would have been parked around the corner. And he doesn’t seem like the tourists who stay at the boarding houses in town. He must have a boat anchored in the bay. He offers to buy me a drink. His Spanish isn’t bad.

“What do you know about Robinson Crusoe?” he asks after I have a gin and tonic in front of me.

“That that wasn’t his name.”

He smiles.

“And what else?” he asks.

“That he came to the Galapagos under orders from Captain Woodes Rogers, that he was a pirate, that he was with Dampier when they attacked Guayaquil, and that his boat sank near here,” I say.

“Full of gold.” When he smiles again, the old man displays a set of perfect dentures.

“That’s what they say.”

Somebody at another table calls to me. I ignore him.

“You don’t believe it?” he asks.

“I believe a lot of things, that doesn’t mean they’re true,” I reply.

In fact, Selkirk is one of my favorite subjects. I’ve read his diary, I know his story backwards and forwards. I’m convinced we would have been friends if I had been born in the eighteenth century. I wouldn’t have thought twice about hanging out with him to soak up some of his knowledge. The guy knew what he wanted. There aren’t many people who do, and then act on it. He asked to be left behind on an abandoned island because the ship’s captain was planning to risk going around Cape Horn in a leaky boat. He survived for four miserable years. But he was luckier than his shipmates, who all died. The old man and I don’t talk about that. We keep speculating about the fate of the ship that went down somewhere in the Galapagos. But when the customers start whistling, I have to leave him. The man, his name is Max, stays until closing.

Everything I know about Selkirk I learned seven years ago when I worked in Victor ́s shop. Victor taught me how to dive. After I’d been working there for three months, he asked me to go with him on a dive. He hired five other divers. We went with our equipment to a boat near the dock. On top of a table in the middle of the boat was a waterproof map. After a few hours sailing, we stopped and got ready to go down, with orders to look for signs of a shipwreck. We stayed down forty minutes and found nothing. We sailed on for half a mile and tried again. We went on like that until we were out of oxygen. On the way back, I sat next to the man giving instructions; he was a historian, a Scot. He asked what it was like to breathe underwater. I don’t know, I told him, I’d never given it any thought. A few minutes later he asked again. The rest were talking about what they were going to eat when they got back and about the price of some new surfboards that had come in on a navy ship. I closed my eyes and tried to remember.

“The first time it was like I’d gone into a woman ́s bedroom while she was taking off her clothes.” I stopped there, but then I thought of something else. “I swam, surprised, for a while until suddenly I was out of breath and the oxygen regulator fell out of my mouth.”

“And what did you do?” He seemed interested.

“I knew I would drown if I didn ́t do something fast, but I didn’t try to climb the twenty-five feet that separated me from the air. I blew bubbles through my nose until I found the mouthpiece, stuck it in and started to breathe again.” I paused there. “I gave myself up to the water and I stopped thinking.” I was quiet again. “It worked.”

I didn’t know what else to tell him but, since he still seemed interested, I went on.

“That got me hooked.”

“I don’t understand. What got you hooked?”

“Having to operate according to a different logic, learning to let go,” I looked at him before going on. “Then,” I paused, “there was the wall.”

“What wall?” he turned to look at me.

“When I went down and into the bedroom where the woman was undressing, the room had no far wall. Since then, I’ve been looking for it.” He looked surprised at what I said.

We were close to Tijeretas. Just around the last reef was the port. Soon it would be dark. The sky was orange with violet streaks. When the sunset the world would disappear.

“The far wall?” he asked.

I could barely see his outline, I couldn’t see his expression, nor how interested he was in my answer.

“The end. It has to be someplace, I keep looking for it,” I said.

Then Victor signaled for me to get the equipment together, we sailed into port, and we unloaded. The rest of the week we kept diving, each time farther out, each time farther down. We found nothing. The same thing happened the following week. On the Monday of the third week, we didn’t go in a boat but, instead, we hauled the equipment onto a yacht with a metal hull, its navigation instruments connected to a satellite. Once there, I heard the historian yelling as he tried to talk to the small man with the captain’s cap. When they were finished arguing, he approached and said to Victor that he no longer needed him, but that he still needed my services to take care of the tanks. With the yacht came fifteen divers trained by the North American navy. They spent a month on San Cristóbal and they didn’t find anything, either. During those thirty days, Will—that was the historian’s name—taught me how to measure longitude and latitude and also told me about Selkirk, Juan Fernández Island, Cape Horn, and about how the English Crown executed the pirates it arrested. Of all the stories he told me, it’s the one I remember best. He told me about it while he drank from a bottle he had chilled in an ice bucket at his feet. He told me that they ordered steel suits made to measure, out of sheets, that left strips of skin exposed. They took the prisoners locked inside those personalized cages to London Bridge where they were crucified in the air. What I mean is, he told me, they were hung with ropes tied to their outstretched arms, gravity did the rest to their joints. From bellow they looked like they were suspended in the air. Birds fought over who would finish them off first. Albatrosses, pelicans, seagulls fighting desperately to tear out the tastiest strips of exposed skin. Will paused and then emptied the bottle, which was more than half full. When he began talking again, he slurred his words and his eyeballs swam in a sea of tears. While they bled to death or the damned birds managed to rip out an organ or they choked while their limbs collapsed—are you listening to me, boy?—they were surrounded by a cyclone of feathers whipped by the gale.

“That guy there,” he signaled the man giving orders, the one with the sailor’s cap, “he’s descended from those kings. Now he’s bent on finding the ship Selkirk piloted after sacking Guayaquil.”

Then he passed out and I carried him to bed. It wouldn’t be long before they stopped trying to find the boat. By then they had spent millions and gotten nowhere and, above all, they ́d given up because the man descended from kings got bored. Among the many lessons I learned from that job, the main one was that I was better off as a free agent. To depend on no one and answer to nothing but my own conscience. The few pirates who died like that had been buccaneers not long before, working for the very queen who ordered their execution. They weren’t punished for what they did but, rather, because of a change in status that meant that certain things that were all right in times of war were not all right in times of peace. Killing, murdering, beheading, and stealing in the name of the queen had been all right when national interests were at stake. Doing the same things, openly, when peace came, turned those same buccaneers into pirates and criminals who had to be hung over the abyss.

I tell him that I don’t think the ship sank where we looked for it seven years earlier. Will followed the coordinates reported in the diary the Duke’s captain published, where there was also a detailed description, not only of Selkirk’s rescue from Juan Fernández and the story of his life on that island, but also of where the ship sank with some of the booty. The man who wrote that was a buccaneer with the mentality of a buccaneer. Would he have published the exact site where his chests of gold had gone down?

“No, Max, never,” I say and he nods.

Ever since Max asked me about Crusoe, he comes to the bar daily. I prefer his company to that of my fellow waiters. I can’t figure him out. He doesn’t have much money but he has enough to make me believe that he has more. I don’t know why he does that, he’s not a swindler. And he’s not a treasure hunter, he’s not full of tales or useless information. He’s interested in the shipwreck, but not obsessed. He doesn’t need to convince me of anything, nor convince himself of something.

“Where would you look for it?” he asks me one day.

“Assuming it’s true that it sank, it would be close to the coast. It must have crashed on the rocks, pulled in by the current.” I pause.

“What do you mean, ‘if it sank,’” he asks.

“The only people who told the story of that trip, the only ones who knew how to write, were Rogers, Selkirk, and Dampier, and they were in command. The only thing they used the Galapagos for was to divvy up the loot and to take on fresh meat and water, no one lived on the islands. On that trip, they were still buccaneers, they had England’s permission to attack the Spanish, but they had to split what they found with the Crown. If the ship disappeared, the booty was given up for lost.”

“You would make a great detective,” he says.

After thinking about that for a minute, I answer, “No, Max, I just think that people assume too many things, one of which is that somebody who writes always tells the truth.”

“Would you teach me to dive?” he asks on another day.

“Go see Victor,” I tell him.

“Victor does everything by the book,” he looks at me with his one good eye. “I wouldn’t even get through his theory classes. Look at me. I have high blood pressure, heart failure, I can barely hear.”

“Why risk it? You could end up down there.”

He doesn’t respond at first, then he goes back to the usual subject. “I want to look for Dampier’s treasure with you,” he says. “I’m not looking for anything,” I reply.

“But you could, right?”

“What are you proposing?”

“That we be partners.”

“I haven’t got a red cent.”

“I do,” he says.

Since I know that’s not true and time is running out, Max is going to have to talk. Does he think I don’t get it? Since he got here, he’s dropped at least ten pounds. For once I shut up. He knows what is going on, and he knows that I know. So? I accept.

Two weeks go by and we still haven’t agreed on a date to begin classes. He’s happier than I’ve ever seen him since the day we met. He writes in a notebook, drinks wine, tells me that the hardest thing for Selkirk to deal with during those four years alone was sadness. That when he touched bottom, when he thought about killing himself, he started talking to the feral cats and goats on the island without realizing what he was doing and then he stopped feeling so lonely. He pauses and then he looks at me. From behind the film his tiny black eyes shine, as though the sky had fallen inside them. Damn, am I ever going to miss him. Then he tells me that Selkirk was thirty years old at the time, that he had his whole life ahead of him. Only then does he say that the next day would be a good day for our first dive. We could do it. I own my own business. It ́s not like Victor’s, I’m not even competition, sometimes he subcontracts me when he has too many customers, and I have my own boat, some equipment, and permits to take tourists out and back. When I agree to teach Max, I know that I’ve risked losing all that. Sometimes we don’t know why we do things but we do them anyway. At least, this time, I know, so I don’t care what might happen. During the last weeks he has given me hints, there are things he wants to tell me, but, since he doesn’t dare, they come in the form of washed out slides. He mentions a redheaded granddaughter with a green checked dress that matches her eyes perfectly, he says in passing that she always smells like spring, even in the darkest days of winter, that the dress reaches just above her knees and that on her right knee there’s always a scab. Things like that, as though he were talking about the treasure. He also talks up his passion for lifting weights and the competitions he’s participated in since he turned thirty-five.

“Last year was the last time,” he pauses. “It was in Tena, I came in first in my division,” he says.

I look at him, surprised. You could break him like a stick, a few feathery plumes are all the hair he has left, his face is covered with liver spots that make him look like he’s been splashed with mud. A champion weight-lifter. I ask why it was the last time.

“There’s no category after eighty,” he says. “And last year wasn’t so great, either. I was the only contestant in my division. But I lifted three hundred and thirty pounds, more than when I was seventy-nine,” he smiles.

So, he’s eighty-one years old, knows the Ecuadorian Amazon, and must feel like the last of the Mohicans. I offer him a drink, we toast. I know some people would frown on what I’m doing with Max, but I could care less, I care about Max. I don’t know if what we’re going to do is what he needs, but I do know that it’s what he wants. I tell him that for a week we’ll snorkel in Tijeretas, that when he’s used to the mask and the fins, we’ll practice with an oxygen tank. When we go down, Max doesn’t take his t-shirt off, he mentions something about the sun and I say nothing but I know that whatever he’s not telling me is under that t-shirt. We see eleven sea turtles scattered on the floor of the bay. A school of blue and yellow tuna move above them like a conga line. I watch Max when we see them. He looks like a moss-covered statue from an ancient civilization set down on the sea floor sediment. The fish slip along the currents and, when they come to the turtles, they open circles around them, creating eleven sanctuaries. The turtles are old and young, male and female. After watching them and resisting the temptation to touch them, Max stops in front of what looks to be the most ancient turtle. He must have been two hundred years old. They look alike, the same cloudy eyes covered with a thin white film and a lost, inward look. I have to force him to leave. The water temperature has dropped suddenly and I’m beginning to get cramps. When we emerge, he hugs me and collapses in my arms, but he doesn’t say anything. That night I don’t see him. The next morning he’s at the door of my shop at eight, more fragile than the day before. He helps me open up, sweeps, and then sits near the door, but he seems to be somewhere else. It’s as though he’s still out at sea, I offer him cup of coffee and he accepts it. Then he says that he doesn’t know if he has seven days to swim in Tijeretas, so why don’t we go ahead and practice with the tank. When I hand him the cup, I see a question mark in his eyes. He puts the cup on the floor and lifts the right side of his t-shirt. An enormous scar, still pink, too recent, crosses from his nipple to the top of his hip. “I only have one lung, I should have died six months ago,” he says. I hear him as if I were listening to the voice of a man who is on the other side of the wall. If someone had hammered my head it wouldn’t hurt as much.

We practice for the first time that same afternoon in a friend’s pool. I don’t let him lift the tank. I tell him to get in the water and I put it on him. The water does the work for him. Max is a natural. In half an hour he has perfected what it takes a lot of people three days to learn. The trick, which he understands immediately, is not to fight the water but to give in to it. Then I explain all the safety measures he needs to take, the difference between air and water pressure. How the lungs (I avoid saying “your lung”) can burst if the diver comes up to the surface too quickly. I talk to him about the oddities of the sea floor, of the changes in perception that you experience down there. About how sounds move and how colors fade and temperatures fall the deeper you get. I notice that Max trembles and coughs and tries to hide it. I tell him I’m tired, that I have a headache, and why doesn ́t he come home with me for a bowl of soup. He surprises me by saying that he would like that very much. He shuffles through the streets and into my living room where he falls into the easy chair. I cover him with a blanket and put a hassock under his feet and tell him I ́ll be right back. He takes my hand and squeezes it. His eyes are closed. He holds my hand in the warmth of his for a few moments and then lets go. Everything swims around me; an emptiness closes in on the both of us. I go to the kitchen, and open the window, the coldness of the living room hasn’t reached here, the heat is a molten liquid that runs through my veins. While I chop an onion and pour oil into a pot, I think of how I’m going to manage it. How I ́m going to get him out to sea, how I ́m going to put weights on him, how long he will take to go down and whether he will be able to come back up. I continue with the carrots and the celery and decide to stop thinking. I look through the door and I don ́t see him, all I see is the mossy statue at the bottom of the sea. From the angle I’m watching him, it seems as if strips of his ashen face are missing, but, still, he smiles. That smile hasn ́t left his face for the last two weeks, he’s like the cat that ate the canary. When the soup is ready, I put it on a tray and take it to him. I leave it on a table and touch his arm.

“It’s ready, Max,” I say.

He doesn’t move. I get down on my knees and put one of my hands over his nose and mouth and I feel nothing. I touch his hand, his warm hand of a few moments ago feels as though it has been two hundred feet under water. I can’t stay upright. When I fall, I see him. He’s swimming with the turtles, they ́re heading toward the far wall.

On the other side, the soup must be getting cold.

_________________________________

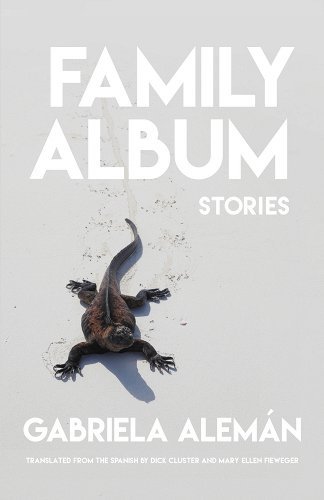

“Baptism” from Family Album: Stories. Copyright © 2010 by Gabriela Alemán. Translations © 2022 by Dick Cluster and Mary Ellen Fieweger. Reprinted with the permission of City Lights Books.