Gabriel García Márquez Remembers His Dearest Friend, Julio Cortázar

"I always thought that death itself seemed indecent to him."

Mexico City, February 12th, 1994–

I went to Prague for the last time, with Carlos Fuentes and Julio Cortázar, in the historic year of 1968. We were traveling by train from Paris because the three of us were united in our fear of airplanes, and we had talked about everything as we crossed the divided night of the Germanys, their oceans of beets, their immense factories which made everything, the devastation of their savage wars and excessive loves.

When it was time to sleep, it occurred to Carlos Fuentes to ask Cortázar how, and at what point, and by whose initiative the piano had been introduced into the jazz orchestra. The question was casual, not meant to find out more than a date and a name, but the answer was a dazzling lecture that went on until dawn, between enormous glasses of beer and icy sausages with potatoes. Cortázar, who knew how to weigh his words very carefully, offered us, with barely credible knowledge and simplicity, a historic and aesthetic review that culminated at first light in a Homeric apologia for Thelonious Monk. He spoke not only in a deep organ voice with laborious long rr’s but with his big-boned hands as well, more expressive than any others I can remember. Neither Carlos Fuentes nor I will ever forget the astonishment of that incomparable night.

Twelve years later I saw Julio Cortázar in front of a crowd in a park in Managua, with no weapons other than his beautiful voice and one of his most difficult stories: the tale of a boxer down on his luck that the protagonist recounts in Lunfardo, the underworld dialect of Buenos Aires, whose comprehension would be completely forbidden to the rest of us mortals if we hadn’t caught glimpses of it through so much malevolence; yet that was the story Cortázar himself chose to read on a platform in a huge illuminated garden before a crowd composed of everyone from consecrated poets and unemployed masons to comandantes of the revolution and their opponents. It was another dazzling experience. Although, strictly speaking, it wasn’t easy to follow the sense of the story, even for the most expert in Lunfardo slang, you felt and were hurt by the blows the poor boxer received in the solitude of the ring, and his illusions and misery made you want to cry, for Cortázar had achieved so intimate a communication with his audience that no one cared any longer what the words meant or didn’t mean, and the crowd sitting on the grass seemed to levitate in a state of grace because of the spell cast by a voice that didn’t seem to be of this world.

These two memories of Cortázar, which affected me so much, also seem to be the ones that defined him best. They were the two extremes of his personality. In private, as on the train to Prague, he seduced with his eloquence, his lively erudition, his millimetric memory, his dangerous humor, with everything that made him one of the great intellectuals in the good sense of another time. In public, in spite of his reluctance to be a spectacle, he fascinated the audience with an inescapable presence that was somehow supernatural and at the same time tender and puzzling. In both cases he was the most remarkable human being I’ve had the good fortune to know.

These two memories of Cortázar, which affected me so much, also seem to be the ones that defined him best. They were the two extremes of his personality.

Years later, when we were already friends, I thought I’d see him again as I saw him that first day, for I think he recreated himself in one of his most accomplished stories, “The Other Heaven”, in the character of a Latin American in Paris who attended executions by guillotine out of sheer curiosity. As if he had done it in front of a mirror, Cortázar described him in this way: “He had at once a distant and curiously fixed expression, the face of someone who has become immobilized in a moment of sleep and refuses to take the step that will return him to wakefulness.” His character went around encased in a long black smock, like Cortázar’s own overcoat when I saw him for the first time, but the narrator of the story didn’t dare approach to ask about his origin, fearing the cold anger with which he himself would have received a similar question.

The strange thing is that I didn’t dare approach Cortázar either on that afternoon in the Old Navy bar, and because of the same fear. I saw him writing for more than an hour, not pausing to think, not drinking anything but half a glass of mineral water, until it began to grow dark and he put his pen in his pocket and went out, his notebook under his arm like the tallest, skinniest schoolboy in the world. On the many occasions we saw each other years later, the only thing that had changed in him was his thick, dark beard, for until two weeks before his death the legend that he was immortal seemed true, because he had never stopped growing and always stayed the age he had been when he was born. I never had the courage to ask him if it was true, as I never told him that during the sad autumn of 1956 I had seen him, without daring to say anything to him, in his corner of the Old Navy, and I know that wherever he is now he must be cursing me for my timidity. Idols fill you with respect, admiration, affection, and, of course, great envy. Cortázar inspired all those feelings as very few writers do, but he also inspired another, less frequent one: devotion. He was, perhaps unintentionally, the Argentine who endeared himself to everybody.

However, I dare to think that if the dead die, Cortázar must be dying again of embarrassment because of the worldwide consternation caused by his death. Nobody dreaded posthumous honors and funeral pomp more than he, either in real life or in books. Besides, I always thought that death itself seemed indecent to him. Somewhere in Around the Day in Eighty Worlds, a group of friends cannot contain their laughter at the evidence that a friend of theirs has committed the absurdity of dying. That was why, because I knew and loved him so well, I refused to take part in lamentations and elegies for Julio Cortázar.

I preferred to go on thinking of him as he undoubtedly would have wanted, with immense rejoicing that he had existed, with deep joy at having known him, and gratitude for his having left the world a body of work that may be incomplete but is as beautiful and indestructible as his memory.

__________________________________

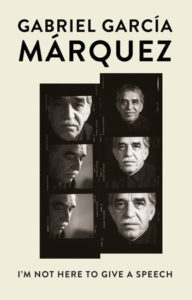

From I’m Not Here to Give a Speech. Used with the permission of Vintage Books. First Vintage International Edition, January 2019. Copyright © 2010 by Gabriel García Márquez. Translation copyright © 2014 by Edith Grossman.

Gabriel García Márquez

Gabriel García Márquez was born in Colombia in 1927. He was awarded the Nobel Prize in Literature in 1982. He is the author of many works of fiction and nonfiction, including One Hundred Years of Solitude and Love in the Time of Cholera. He died in 2014.