Gabriel García Márquez: On Taking Writers at Their Word

Not Exactly Against Interpretation, But Close

A literature teacher warned the youngest daughter of a great friend of mine last year that her final exam would be on One Hundred Years of Solitude. The girl was frightened, with every reason, not only because she hadn’t read the book, but because she was concentrating on other, more important subjects. Luckily, her father has a very serious literary education and a poetic intuition like few others, and he subjected her to such an intense preparation that, undoubtedly, she arrived at the exam better armed than her teacher. However, he asked her an unexpected question: What is the meaning of the backward letter in the title Cien años de soledad ? He was referring to the Buenos Aires edition, the cover of which was designed by the painter Vicente Rojo with one letter turned backward, because his absolute and sovereign inspiration instructed him to. The girl, of course, did not know how to answer. Vicente Rojo said when I told him that he wouldn’t have known either.

That same year, my son Gonzalo had to answer a literature questionnaire prepared in London for an entrance exam. One of the questions purported to establish what the rooster symbolized in No One Writes to the Colonel. Gonzalo, who is very familiar with our house style, could not resist the temptation to pull the leg of that distant scholar, and answered, “It is the rooster of the golden eggs.” We later learned that the person who received the highest grade was the student who answered, as the teacher had taught him, that the colonel’s rooster was the symbol of the repressed power of the people. When I found that out, I was again glad of my tactful lucky star, for the end of the book I had planned, and which I changed at the last minute, was to have the colonel wring the rooster’s neck and make out of him a soup of protest.

For years I’ve been collecting these pearls bad teachers of literature use to pervert children. I know one who in very good faith believes the heartless, fat, and voracious grandmother who exploits the naive Eréndira to collect a debt is the symbol of insatiable capitalism. A Catholic teacher taught that Remedios the Beauty’s ascent to the sky is a poetic transposition of the Virgin Mary’s ascension in body and soul. Another taught a whole class on Herbert, a character from some story of mine who resolves problems for everyone and gives away money hand over fist. “He is a lovely metaphor for God,” said the teacher. Two Barcelona critics surprised me with the discovery that The Autumn of the Patriarch has the same structure as Béla Bartók’s third piano concerto. That caused me great joy because of the admiration I have for Béla Bartók, and especially for that concerto, but I still haven’t been able to understand those two critics’ analogies. A literature professor at the Havana School of Letters spent many hours on an analysis of One Hundred Years of Solitude and reached the conclusion—flattering and depressing at the same time—that it offered no solution. Which completely convinced me that the interpretive mania eventually ends up being a new form of fiction that sometimes gets stranded on a foolish remark.

I must be a very ingenuous reader, because I’ve never thought that novelists mean to say more than what they say. When Franz Kafka says that Gregory Samsa woke up one morning transformed into a gigantic insect, it doesn’t strike me as a symbol of anything, and the only thing that has always intrigued me is what kind of creature he might have been. I believe that in reality there was a time when carpets flew and genies were imprisoned in bottles. I believe Balaam’s ass spoke—as the Bible tells us—and the only regrettable thing is that his voice was not recorded, and I believe that Joshua destroyed the walls of Jericho with the power of his trumpets, and the only regrettable thing is that no one transcribed the demolition music. I believe, indeed, that the lawyer of glass—by Cervantes—really was made of glass, as he believed in his madness, and I truly believe in the joyful truth that Gargantua pissed in torrents over the cathedrals of Paris. Even more: I believe other similar wonders are still happening, and if we don’t see them it is in large measure because we are impeded by the obscurantist rationalism inculcated in us by bad literature teachers.

I have great respect, and most of all great affection, for the job of teacher, and that’s why it hurts me that they too are victims of a system of learning that leads them to spout nonsense. One of my unforgettable beings is the teacher who taught me to read at the age of five. She was a lovely and wise girl who didn’t pretend to know more than she knew, and she was also so young that with time she has ended up being younger than me. She was the one who read to us in class the first poems that rotted my brain forever. I remember with the same gratitude my high school literature teacher, a modest and prudent man who led us through the labyrinth of good books without farfetched interpretations. This method allowed his students a more personal and free participation in the wonder of poetry. In short, a course in literature should not be much more than a good reading guide. Any other pretension is no use for anything but frightening children. That’s what I think, here in the back room.

–January 27, 1981, El País, Madrid

__________________________________

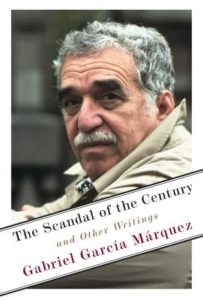

From the book The Scandal of the Century: And Other Writings by Gabriel Garcia Marquez. English translation copyright © 2019 by Heirs of Gabriel Garcia Marquez. Published by arrangement with Vintage Books, an imprint of the Knopf Doubleday Publishing Group, a division of Penguin Random House LLC.

From the book The Scandal of the Century: And Other Writings by Gabriel Garcia Marquez. English translation copyright © 2019 by Heirs of Gabriel Garcia Marquez. Published by arrangement with Vintage Books, an imprint of the Knopf Doubleday Publishing Group, a division of Penguin Random House LLC.

Gabriel García Márquez

Gabriel García Márquez was born in Colombia in 1927. He was awarded the Nobel Prize in Literature in 1982. He is the author of many works of fiction and nonfiction, including One Hundred Years of Solitude and Love in the Time of Cholera. He died in 2014.