I came to Paris for the first time one freezing December night in 1955. I arrived by train from Rome to a station decked out with Christmas lights, and the first thing that caught my attention were the couples who kissed each other everywhere. On the train, in the metro, in cafés, on elevators, the first postwar generation threw themselves with all their energy into the public consumption of love, which was still the only cheap pleasure after the disaster. They kissed in the middle of the street, with no worries about hindering pedestrians, who moved aside without looking at them or paying any attention, as we do with stray dogs that hang onto each other, making puppies in the middle of the town square. Those outdoor kisses were not frequent in Rome—which was the first European city I’d lived in—nor, of course, in the misty and prudish Bogotá of those days, where it was even difficult to kiss in bedrooms.

This was in the dark days of the war in Algeria. In the background of the nostalgic accordion music on the corners, beyond the street smell of chestnuts roasting in the braziers, repression was an insatiable specter. All of a sudden, the police would block off the exit of a café or of one of the North African bars on the Boulevard Saint-Michel and violently drag away anyone who didn’t have a Christian face. One of those, inevitably, was me. No explanations worked: not just our faces, but also the accent with which we spoke French, were reasons for our undoing.

The first time they put me in the cage with the Algerians, at the Saint-Germain-des-Prés police station, I felt humiliated. It was a Latin American prejudice: jail was something to be ashamed of then, because as children we didn’t have a very clear distinction between political and common crimes, and our conservative adults took care of inculcating that confusion and keeping us in it. My situation was even more dangerous, because, even though the police dragged me away because they thought I was Algerian, once inside the cell the Algerians distrusted me when they realized that, despite my face of a door-to-door fabric salesman, I did not understand a single word they said.

However, since they and I continued to be such assiduous visitors to the nocturnal lockups, we ended up reaching an understanding. One night, one of them said if I was going to be an innocent prisoner wouldn’t it be better to be a guilty one, and put me to work for the Algerian National Liberation Front. He was Ahmed Tebbal, a doctor, who was one of my best friends in Paris during those days, but he died of a different war death after the independence of his country. Twenty-five years later, when I was invited to the celebration of that anniversary in Algeria, I declared to a journalist something that seemed hard to believe: the Algerian Revolution is the only one for which I’ve actually been imprisoned.

I am most grateful to that city, with which I have many old grudges, and many even older loves, for having given me a new and resolute perspective on Latin America.

Nevertheless, Paris back then was not only a city of the Algerian War. It was also the place for the most generalized exile of Latin Americans in a long time. In effect, Juan Domingo Perón—who was not the same then as in later years—was in power in Argentina, General Ordía was in Peru, General Rojas Pinilla was in Colombia, General Pérez Jiménez was in Venezuela, General Anastasio Somoza was in Nicaragua, General Rafael Leónidas Trujillo was in Santo Domingo, General Fulgencio Batista was in Cuba. We were so many fugitives of so many simultaneous patriarchs that the poet Nicolás Guillén would lean out over his balcony of the Hotel Grand Saint-Michel, on Rue Cujas, every morning and shout out the news from Latin America in Spanish. One morning he shouted, “The man has fallen.” Only one man had fallen, of course, but we all woke up with the illusion that the fallen general was the one from our own country.

When I arrived in Paris, I was nothing but a raw Caribbean. I am most grateful to that city, with which I have many old grudges, and many even older loves, for having given me a new and resolute perspective on Latin America. The vision of the whole, which we didn’t have in any of our countries, became very clear here around a safe table, and one ended up realizing that, in spite of being from different countries, we were all crew members of the same boat. It was possible to travel all around the continent and meet its writers, its artists, its disgraced or budding politicians, just by making rounds of the crowded cafés of Saint-Germain-des-Prés. Some didn’t arrive, as happened to me with Julio Cortázar—whom I already admired for the wonderful stories of Bestiario—and for whom I waited for almost a year in the Old Navy café, where someone had told me he often went. I finally met him fifteen years later, also in Paris, and he was still as I’d imagined him since long ago: the tallest man in the world, who never decided to grow old. The faithful copy of that unforgettable Latin American who, in one of his short stories, liked to walk through the misty dawns to go and watch the guillotine executions.

We breathed in the songs of Brassens in the air. The lovely Tachia Quintana, a bold Basque woman whom we Latin Americans from all over had adopted as one of our own exiles, performed the miracle of making a succulent paella for ten on a tiny spirit stove. Paul Coulaud, another of our converts, had found a name for that life: la misère dorée, golden misery. I didn’t have a very clear appreciation of my situation until one night when I found myself near the Jardin de Luxembourg without having eaten a chestnut all day and with no place to sleep. I was wandering the boulevards for hours, in the hope that a police patrol sweeping the streets for Arabs would pick me up so I could sleep in the warm cell, but no matter where I looked I couldn’t find one. At dawn, when the palaces along the Seine began to show their silhouettes in the thick fog, I headed over to the Îsle de la Cité with long, decisive strides and with the face of an honest worker who’s just got up to go to his factory. As I was crossing the Saint-Michel bridge, I sensed that I was not alone in the fog because I could clearly hear the footsteps of someone approaching from the opposite direction. I saw him take shape in the fog, on the same sidewalk and with the same rhythm as me, and I saw up close his red and black plaid jacket, and in the instant our paths crossed at the middle of the bridge I saw his unruly hair, his Turk’s moustache, his sad countenance of backdated hunger and sleepless nights, and I saw his eyes brimming with tears. My heart froze, because that man seemed to be me, on my way back.

That’s my most intense memory of those times, and I’ve remembered it with more force than ever now that I’ve returned to Paris on my way back from Stockholm. The city has not changed since then. In 1968, when I was lured by my curiosity to see what had happened after that marvelous explosion of May, I found that lovers were not kissing in public, and they’d replaced the cobblestones in the streets, and they’d erased the most beautiful graffiti ever written on walls: “Imagination to power,” “Beneath the pavement, the beach,” “Make love on top of the others.” Yesterday, after walking around the places that were once mine, I could only perceive one novelty: some municipal workers dressed in green, who traveled the streets on green motorcycles and carried mechanical hands like space explorers to collect from the street the shit that a million captive dogs expel every twenty-four hours in the loveliest city on earth.

December 29, 1982, El País, Madrid

![]()

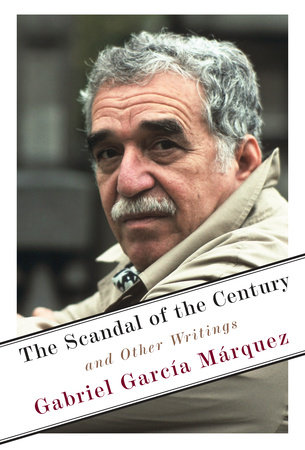

Excerpted from The Scandal of the Century and Other Writings. Copyright © 2019 by Gabriel García Márquez. All rights reserved. No part of this excerpt may be reproduced or reprinted without permission from the publisher.

Gabriel García Márquez

Gabriel García Márquez was born in Colombia in 1927. He was awarded the Nobel Prize in Literature in 1982. He is the author of many works of fiction and nonfiction, including One Hundred Years of Solitude and Love in the Time of Cholera. He died in 2014.