Gabriel Byrne on Struggling With Authenticity in the Wake of Fatherly Expectation

“To be on the scrap heap was to be shamed. A man worked.”

I begin to apply my makeup. My mask. Our tragedy, O’Neill said, is that we are haunted not just by the masks others wear but by the masks we wear ourselves. We all act all the time. Life makes us necessary deceivers. Except maybe when we are alone. As I am now in the windowless dressing room of a Broadway theater.

I struggle with authenticity. Being truthful. Both to myself first and to other people. Is it possible to be completely honest with myself? To admit my fears, my demons, prejudices, the petty envies, the unfulfilled desires? I want to live an authentic life. To take off the mask requires courage. I admit my fragility, my vulnerability and weakness. Why are we so afraid to let others see us as we truly are? Can you ever really know another human being? There is a locked room which we ourselves dare not enter for fear. Fear of what exactly I don’t know. Maybe that is one of the necessities of fiction. It allows us to experience the hidden depths of ourselves and to acknowledge that we are all made of the same human stuff.

I am by nature an introvert. For a long time I was ashamed of this. As if it were somehow a moral failing. I never felt I belonged anywhere. Was always trying to be as real as I could. Seeking authenticity. But paralyzed by my mask and the masks of others. I can be sociable too. But it drains me of energy and I have to find refuge in solitude again. I have few friends. That also used to mortify me. Aren’t you supposed to have huge parties where scores of successful witty people surround you?

No one else can play the part of me.

–You can’t trust actors, a producer said to me once, half-jokingly, because they are always pretending. They lie.

–No, I replied, our job is to try to tell the truth. We are the channels through which the truth comes. There is no play without the actor, no actor without the words.

I look into the mirror. My father’s face looks back at me. I see him dipping his cut-throat in the rainwater barrel, shaving in the cracked mirror which divides his face in two.

I struggle with authenticity. Being truthful. Both to myself first and to other people. Is it possible to be completely honest with myself?–Do you remember the time I finally got you to come for a meal in a restaurant?

–Sure where would I be going eating a meal in a restaurant and having to pay through the nose for food you could get in the supermarket for a quarter of the price?

–That’s not the point. I wanted to treat you.

–Sure treat me for what?

–Just. That’s all.

You were dressed in your one good suit, collar and tie under the pullover. Shoes, as always, polished. Your only extravagance.

–You can tell a man by his shoes, you always said.

We were shown to our table by a deferential waiter. He made a big show of saying he was a fan. He ignored you until I introduced you.

–A pleasure to meet you, sir, he said, bowing slightly from the waist.

–Jaysus, these are huge menus. You’d have to pass an exam just to read them. You wouldn’t know what half of these yokes are.

At home I rarely saw you sit at the table. There was never enough room in the kitchen for us all to sit together so you would stand with one hand leaning on the chair and bless yourself before and after each meal.

The waiter brought a selection of breads. Whole wheat, peasant raisin, sourdough rye, pumpkin.

–I’d like a bit of brown, if you have it, you said. You always loved Mother’s brown bread.

–If I may recommend our lobster bisque, offered the waiter.

*

You used to make soup from the boiled heads of sheep and pigs, and chew the pig’s ears and feet, with fried bread and dripping.

I look into the mirror. My father’s face looks back at me. I see him dipping his cut-throat in the rainwater barrel, shaving in the cracked mirror which divides his face in two.–There’s great nourishment in the brains too, you’d say. You used to cook huge pots of rice and a lumpy thing called sago.

–You’re not cooking for soldiers in a barracks, Mother would say.

–Did you know that in the Siege of Drogheda the people were that hungry they had to eat rats? An awful bastard Cromwell. The curse of God on him.

–Please, Dad, not now.

*

–Have you had a chance to look at the wine list, gentlemen?

–Would they give me a pint of Guinness, do you think? you whispered to me.

–They’ll get you anything you want.

–You don’t have to be spending all this money. You have to look after your pennies and the pounds will take care of themselves, a wise man said. You were always quoting this wise man, whoever he was.

We were uneasy together in the formality of the restaurant. Halfway into your pint you became expansive.

–You did well for yourself getting your degree at the university. The first of the family ever to get to a university. And a scholarship no less. And now you’re on the television. You’re as well known as Doran’s donkey.

–Remember when I asked you to come and see me in my first play? And you asked how much it was to get in? I told you five quid and you said, Sure I can see you at home for nothing.

–You were bollock naked in it.

–Only for a few seconds.

–Nearly had to cart your mother off to intensive care. I thought you would have stuck at the old plumbing game.

–I wasn’t cut out for it. I was useless.

–Still you can’t beat a trade, as the fella says. It’ll always stand to you.

You ordered another pint and the food arrived.

You said to the waiter:

–Them spuds are tasty alright, grand bit of meat too.

There was more silence. We made small talk about the restaurant. Football. You lit your pipe. The bill arrived.

–What’s the damage? you asked.

–Doesn’t matter. It’s my treat.

–Sure let me go halves.

–No.

–Go on. Tell us how much.

–Seventeen pounds, if you must know.

–Seventeen pounds. Lord Jaysus. At least Dick Turpin had the courtesy to wear a mask when he robbed people.

*

Every morning, my father and his friends would walk three miles to the chapel for early mass and then into the taproom of the Guinness brewery, a pint of undiluted stout to start the day. They were coopers’ laborers, hauling and shaving and planing wood for the staved barrels that would be rolled to the trucks and ferried off to the docks for England, or to the barges to bring porter to the faraway towns of Ireland. My father was proud of that ancient trade and the language that went with it.

Then, one day, they were told they would be needed no more. That they were laborers, not skilled men. On the scrap heap at 48 years of age, too young to retire, too old to find another job in a changing world. They got a lump sum, a small pension, and a clock. After thirty years.

–What use is a fucking clock only to remind you of how fast the years have gone and the few you’ve got left?

There was a dinner to which all the families were invited. Speeches were made by managers they rarely met. Applause and toasts and photographs.

To be on the scrap heap was to be shamed. A man worked, he brought home wages in a brown packet, placed them on the mantelpiece, and was handed back a few pounds by his wife for cigarettes and beer. But there was no talk of feelings or emotional pain, so my father sought refuge in silence.

He got a part-time job trimming hedges, and even though it was odd-job work, he put on a tie because he was going to work for a posh woman who he said was gentry. She didn’t like “the laborers,” as she called them, to eat in the house. I would think of my father sitting looking at her big house as he ate his sandwiches in the garden. Then winter came and there was no need for him anymore, and he wasn’t called back in spring or summer. Our mother became the breadwinner, working in the hospital, the one who left early now and didn’t return until late.

Every day, my father would take the dog for a walk on the hill road. Later when he got sick, I took over walking her. She would skid to a halt outside the pub and go straight to the barman.

To be on the scrap heap was to be shamed. A man worked, he brought home wages in a brown packet, placed them on the mantelpiece, and was handed back a few pounds by his wife for cigarettes and beer.–That dog would sit up on the stool and order himself a pint and a bag of crisps, the barman laughed.

After that job as a gardener, my father never worked again. But still he kept that cheap clock on the shelf, winding it every night, though it was always ticking too slow or too fast.

His wavy hair that all the women admired turned thin and grey. He became stooped and walked with labored breath, his clothes loose about his body, specks of dried blood where the razor grazed him; his hands had begun to shake, and he seemed bewildered by life.

He had never questioned the political and economic system which condemned him to the scrap heap.

–You live the life you are given, he always said.

*

For the 2017 Academy Awards, Rolex wanted to acknowledge actors who had worn their watches in film. There was Paul Newman, Marlon Brando, Peter Sellers, Benicio del Toro, Charles Bronson, and myself, among a few others. I received a gold timepiece with my name inscribed on the back, a one-off special edition. Paul Newman’s 1968 Rolex Daytona sold at auction for fifteen million dollars after twelve minutes to a bidder on the telephone, the highest price ever paid for a wristwatch.

–A world gone mad, I could hear you say. The biggest sin is wasting time. When your ship comes in, make sure you’re on the dock to meet it, as the wise man said.

It’s funny how I half-listened to you, or didn’t listen at all, for so many years. It’s only now I hear you.

When you died at the hospital, they brought us what they called your “effects”: toothbrush, razor, prayer book, the clothes you thought you would go home in; all that remained of you. The most valuable thing you owned, a vintage watch from the fifties with a cream dial, the numbers picked out in gold, Swiss made, seventeen jewels in a stainless steel case, water-resistant and antimagnetic. The brown band frayed with your sweat. It had been on your wrist as long as I could remember, beneath the crooked tattoo of a crucifix.

–You have to wind this fella with care between your finger and thumb, always in a forward direction.

As you got older you would bring it closer to your eyes, squint at it as I made to go, anxious to be away.

Later, when I’d visit you, you’d say:

–You can stay a few minutes yet. I’ll put the kettle on.

When you died at the hospital, they brought us what they called your “effects”: toothbrush, razor, prayer book, the clothes you thought you would go home in; all that remained of you.Now I understand that was your way of telling me you loved me. Hanging onto those last moments between us.

Late one night on the Bridge of Sighs in Venice, as I straggled back to my hotel after a night of drinking, I was pointing down to the canal when your watch slipped from my wrist into its dark depths. Maybe jewelry comes into one’s life for a reason and leaves for a reason, and like everything in this world we must be prepared to let it go. Yet so many times I have imagined the journey of your watch to the silt below, imagined it resting there, not rusted but shining, still ticking, real as anything and forever unreachable. Like the past.

*

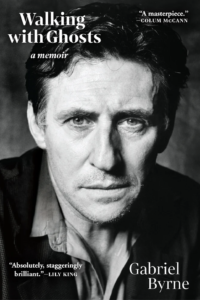

Join Gabriel Byrne and Lily King in conversation about Walking with Ghosts. Register here.

__________________________________

From Walking with Ghosts by Gabriel Byrne. Used with the permission of Grove Press. Copyright © 2021 by Gabriel Byrne.

Previous Article

The Woman Who Ran for President Before WomenCould Vote

Next Article

Surviving Your Thirties: AKA thePanic Years