Funeral For a Postponed Death: On Burying Argentina’s Disappeared

Mariana Enriquez: “How beautiful cemeteries are.... Where the name and the date remain, a voice that says: I was here, now I’m gone.”

Translation by Megan McDowell

In the middle of August 2011, I received an email from my colleague and friend Marta Dillon. It was an invitation to the burial of Marta Taboada, her mother, who had been disappeared. The message—it wasn’t sent to me exclusively, of course; it was an open invitation—said:

Friends, comrades:

There are moments in life when we need an embrace. When these words, friends and comrades, become indispensable. On August 27, thirty-five years after the last time we were able to embrace her, we will finally bury my mother, who was kidnapped and disappeared on October 28, 1976, along with Juan Carlos Arroyo and Gladys Porcel, all three of whose bodies were identified by the Argentine Forensic Anthropology Team last year.

The message went on to tell the story of her mother’s political militancy, and it invited us to meet in the main square of Moreno, a town some forty kilometers west of Buenos Aires, on August 27 at eleven-thirty AM.

Too much traffic, too much vertigo, too many incomplete explanations because everyone was trying to feign a composure that no one, not even the most distantly related, could maintain.

I knew that Marta Taboada’s body had been found, because her daughter, also named Marta, had written about it in the newspaper where we both worked. I’d learned the details in an article published on the back page of Página/12 on November 24, 2010:

My mother was murdered on February 3rd, 1977, at 2:05 in the morning, on the corner of Santamarina and Chubut, Ciudadela. Her death certificate says: “Multiple bullet wounds. Jane Doe, thin, 5’4″, dyed blond hair…” My mother is now, concretely, a skull with a few teeth, a morphologically designated jaw, tibias and femurs, radii and ulnas, clavicles. I’m sure I’m making mistakes in this listing of bones, but I do know that her torso is still missing. She, however, is not.

I remember that I sent Marta an email with a subject line that read “Uf.” The body of the email was only: “Martita, your back page today is extraordinary. Extraordinary. I don’t have much else to say, I’m still in shock.” I don’t think I ever spoke directly to her about her mother’s reappearance.

I did know the details, though. How Marta (mother) had lived clandestinely, a militant member of the Frente Revolucionario 17 de Octubre, in a house in Moreno on Calle Joly, near the train station, with her four children (Marta, Andrés, Juan, and Santiago), her boyfriend, Juan Carlos, and Gladys Porcel. How a squad had burst into that house, taken away the adults, and left the children behind, all witnesses to the kidnapping.

Marta Taboada was thirty-five years old. Marta, her daughter, was ten. It was October 28, 1976. They took Marta Taboada to a clandestine detention center in La Matanza called Proto Blanco—also known as Brigada Güemes, and usually lumped in with the El Vesubio detention center, which was across from it. A little over three months after the kidnapping, she was shot and buried in a common grave in the San Martín Cemetery. Now, reappeared and identified by the Argentine Forensic Anthropology Team, she was going to be given a proper burial.

I had to go. I don’t have a car and I’d never been to Moreno, but I had to go. I felt it was urgent: attending Marta Taboada’s funeral was a political act, but it was also something as simple as being there for someone, as mourning, as ritual.

After a few phone calls, our group was set: Raúl, who’s Colombian, at the wheel; Vanina, who knows the Western Zone, as navigator in the passenger seat; Patricia and me in the back. The cold on August 27, 2011, was unprecedented—unbridled, utterly cruel.

We left in a caravan from the home of Marta and her wife, Albertina, in Saavedra. We were supposed to follow Marta, or Marta’s brothers, or Josefina, or Raquel—both close friends of Marta’s, both daughters of disappeared mothers, as was Albertina—but it was impossible. Too much traffic, too much vertigo, too many incomplete explanations because everyone was trying to feign a composure that no one, not even the most distantly related, could maintain.

Far ahead of our car, we saw the white coffin. We followed it as long as we could, but then we got lost along the horrible gray Acceso Oeste Highway. We called people, received calls (“I got off at the wrong exit—I don’t know where I am!”); we turned around randomly in the middle of garbage dumps and wastelands, in that post-apocalyptic landscape you often see in Greater Buenos Aires.

Finally, we reached the Moreno plaza. By then the ceremony was wrapping up, but we didn’t care.

*

We had arrived in time to accompany the coffin, in its hearse, to the door of the house on Calle Joly, where the three dead activists were to be honored with commemorative paving stones. There were a lot of people, maybe more than five hundred, activists and relatives and friends and comrades.

Marta Taboada’s casket was atop the hearse, covered in a white cloth and surrounded by carnations. It was—is—a beautiful coffin, or more like a jewel box, or an urn. Marta and her friends, twelve women, had spent Saturday night decorating it. Albertina had ordered the box made. The artist Alejandra Fenocchio had painted a Montonera Evita, her blond hair flowing. The others had painted red flowers and glued on green, blue, and orange cloth flowers; they drew a blond woman on the beach in a bikini, and added a small black-and-white photo of Marta, as well as a black heart and pearls like droplets. To one side, in green, the word Mamá was written in little stones made of green clay. There was also another inscription: “Sister, friend, lover, mother, activist, grandmother, great-grandmother.”

The ceremony for the paving stones was long. There was a speech from Gladys’s son, Tupac Vladimir, who had been four or five at the time of the abduction. There was another speech, from Raquel Robles, a writer and activist in HIJOS (Sons and Daughters for Identity and Justice Against Forgetfulness and Silence), whose steady firmness was remarkable, almost severe. She read out a long list of names of supporters, because, she said, they had waited thirty years for this moment and what did it matter if they waited a little longer. She was right.

Marta, in a red sweater, leaned against her mother’s casket as she spoke. “I’m not going to say much,” she began. “There are moments that seem a lot like that Victory we always talk about. I think that this moment, with all of us here together, feels like Victory. There’s still a lot more to come. We still need to find out who fired, who moved the bodies from that corner of Ciudadela, who filled out the death certificates as Jane and John Does with false information. It’s a lot, but we’ll get there.” She posed for a photo with her fingers in a V, smiling and crying.

From there to the Moreno cemetery in La Reja, down Ruta 7. I got the chance to hug Marta at the entrance. In a clearing, we all tried to fit into a circle, with the casket at the center. I saw that the top of it read, “Until victory always,” and that it had an image of two crossed red rifles. A cleric from the Movement of Priests for the Third World invited people to join in a song. Marta’s brothers sobbed with the desperation of years, with childish anguish. There were words from Nora Cortiñas and Lita Boitano (the former a founder of the Mothers of the Plaza de Mayo, the latter the president of Families of Those Disappeared and Detained for Political Reasons). The cold was awful, but the rain that was predicted never came.

Then it was time to take Marta to the Taboada family vault and place her beside her parents. It was hard to fit in that narrow pathway of the Moreno Cemetery; I ended up close enough to see the casket enter the vault and, finally, the unleashed tears of Marta and her wife as they embraced. Someone was playing the guitar, and it seemed like the moment to give my spot to someone else, because everyone wanted to touch the now-closed grave and shout again: “Marta Taboada…presente, ahora y siempre,” the way they’d been doing since early that morning.

I circled the Taboadas’ vault and walked away from the songs and the red carnations. Near a structure of niches, I found the most extraordinary monument. A sort of anonymous stone altar, broad and low, with a little flight of stairs, something like a gazebo without a roof. It was full of things. Lit candles, images on paper and a plaster statue of the folk saint Gauchito Gil, flowers in green plastic bottles, simple bouquets of jasmine floating in rotten water inside coffee cans, a lot of plastic flowers to keep the place colorful. But most of all, this altar of the dead was covered in photos. Typical gravesite photos, sepia and oval, in frames. Who placed them here? Is it a custom at the La Reja cemetery to collect these photos when they fall off from rust and time, and instead of returning them to the graves where they belong, bring them here? Or are they photos of bodies that have been dug up from the ground and “reduced”?

Attending Marta Taboada’s funeral was a political act, but it was also something as simple as being there for someone, as mourning, as ritual.

In many municipal cemeteries, bodies are exhumed in order to make room for more. The bones are put into a niche or an urn, or they’re cremated and placed in a family home—that is, they end up somewhere other than in the ground. What happens to the photographs then? Some people must take them, but others must be abandoned. In that case, do the caretakers bring them here?

At La Reja, in Moreno, there is someone who places the pictures on this altar, along with candles that are lit even in the cold wind, set on little dishes, the melted wax creating fantastic shapes. The faces on the photos are anonymous, one beside another, no names, no dates of birth or death. A long-haired boy of around twenty smiles beside a very serious woman with her black jacket buttoned all the way up. An elderly couple is next to a mustachioed man who could be a tango singer. A very young woman with a bouffant (very 1960s), next to a man with slicked-back hair.

There are also plaques with birth and death dates, which were once on graves and were later relocated here. They don’t match the photos. It’s a mixture: a waist-up photo of a smiling little girl with neat bangs and narrowed eyes, beside a photo of a woman with an impressive nose, wearing a mantilla, and beneath them, a plaque that says, “Oscar Alfredo Velazques.”

Someone has also brought an angel that is so worn away it hardly has features or wings. There are a lot of carnations. The same flowers that accompany Marta.

I go back to the cortege. It’s time to go home. Some people are going to meet at Marta’s house. The four of us who rode together decide to return together as well, each to his or her house. Getting back is extremely, ridiculously easy, so different from the drive there that we have to laugh. We are relieved and content.

In her invitation, Marta had said, “We will walk five blocks to the house where she was abducted to place a paving stone with her name into the sidewalk, and then we’ll go to the cemetery, where she will finally rest in peace, beside her deceased parents, in a place where people can read her epitaph.”

How beautiful cemeteries are, I think as I look out the window at the gray sky. My friend Patricia is asleep beside me. “Where people can read her epitaph.” Where the name and the date remain, a voice that says: I was here, now I’m gone. Maybe no one knows my name anymore, but someday someone will remember me.

__________________________________

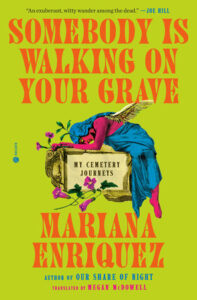

From the book Somebody Is Walking on Your Grave: My Cemetery Journeys by Mariana Enriquez, translated by Megan McDowell. Originally published in Spain as Alguien camina sobre tu tumba. Copyright © 2021 by Mariana Enriquez. Translation copyright © 2025 by Megan McDowell. Published in September 2026 by Hogarth, an imprint of Random House, a division of Penguin Random House LLC. All rights reserved.

Mariana Enriquez

Mariana Enriquez is a writer based in Buenos Aires. She has published in English the novel Our Share of Night and three story collections, A Sunny Place for Shady People, Things We Lost in the Fire, and The Dangers of Smoking in Bed, which was a finalist for the International Booker Prize, the Kirkus Prize, the Ray Bradbury Prize for Science Fiction, Fantasy & Speculative Fiction, and the Los Angeles Times Book Prize in Fiction.