As a freshman member of Congress in 1991, the same year that she joined the Financial Services Committee, Maxine Waters was also on the Veterans’ Affairs Committee. No sooner had Waters arrived in Washington than she once again had a Goliath that she’d have to conquer.

She joined the committee knowing that she was the only woman and only Black person. The committee chair was Sonny Montgomery from Mississippi, a retired National Guard Member with a reputation for being strict, Oh, sis, I know, how are these two going to mesh, right? He was known for running the committee with an iron fist, eek.

Waters wasn’t afraid. Did we expect her to be?

Montgomery was equally notorious for having no, zero, zilch tolerance for lateness. But Auntie Maxine had trouble finding the room that first day. It was on a different floor from what she expected, and in the end, she arrived a few minutes late. She walked in and sat down quietly, took a look around the room—white man, white man, white man, and so on.

It was all white men, as they’d said. Auntie Maxine is no punk at all, what she told Angela Rye on On the One is that she thought, Huh, he better not mess with me. (Auntie is gangsta, y’all!)

Montgomery, a former state trooper, was not one to be messed with either. Black, white, woman, man . . . What these two did have common was a notorious bite‑back.

Anyway, the conversation starts rolling around the room. Everyone sharing their two cents. As the newbie, Waters wanted to put in her opinion about cost. She was perplexed about the prevailing notion that Montgomery didn’t seem to want any of the committee members to propose anything that cost money, which she found ridiculous.

Maxine Waters was a freshman in an all‑male locker room, a 55‑year‑old woman, and there was no need to hesitate or try to win friends anyway.If the funding for their bill got turned down, that was fine, but to not even ask? . . . Well, that wasn’t at all what Auntie Maxine had learned legislation is all about. When it was her turn to speak, she said this to him in her own way, which is usually straightforward, and of course he didn’t like it.

He disagreed, of course, but when he decided to be vindictive and salty about it and pop off in front of everyone about Auntie having been only a few minutes late on her first day, Oh Lord, help him. . . .

“By the way, Maxine, this committee starts on time.”

Maxine, huh? Maxine, who?

Auntie probably started to see stars—WTH was he saying? Maxine? Did he know her from family picnics, did they go to the salon together, was he in her swim class? No. Then why the heck was he calling her by her first name? No, no, no, sir. She was a freshman in an all‑male locker room, a 55‑year‑old woman, and there was no need to hesitate or try to win friends anyway, but she caught herself. She bit her tongue. She told Angela Rye that she took a deep breath to let it sit for a while.

Breathe. Breathe. Breathe. She asked herself therapeutic questions: Was it a problem that he called her Maxine? Did he mean anything by calling her by her first name? Hmmm. Was he calling her Maxine like the help, “Hey, maid Maxine, come to work on time”? Hmmm. Was she not a member of Congress? she remembered thinking.

She collected Aunt Jemima figures due to her own respect for their history, but there was no way that she’d be treated like an underling today. (To Auntie Maxine, Aunt Jemima memorabilia represented the endurance of Black women who came before her. “They have so much wisdom. They worked hard, they scrubbed floors, they raised the children, they nurtured their men. I just love that this Black woman, as exemplified by Aunt Jemima, is probably what held this race together.”)

The problem of the moment was really his audacity to even go there. Had he ever or would he ever think to address a male member this way? It was pure shade. Hell no, she wasn’t going to allow that, but she bit her lip the entire meeting. She explained to Rye when to throw shade and when to hold back:

I have this thing about life. You fit your lines of action. If I am at a cocktail party, talking nicey-nice, if I’m in a back room where the fight is on, I know how to say son-of-a-bitch as well as anybody, and will fight as hard as anybody. But it really is [about] fitting your lines of action.

I don’t pretend to be happy all the time. I don’t pretend to be nice no matter what. I don’t take insults no matter what. Some people are trained to do that better than others. When you’ve basically come from a poor background, you’re not really trained that way. I didn’t go to finishing school.

But right after the meeting, when first‑name‑calling Montgomery was packing up all his notes and was ready to shuffle back down the hall to his office with all of his bros, Auntie Maxine waited to the side until there was room for her to move in on him calm and smoothly, and when she did, she said, as she told Rye, “I need to see you,” He was thrown. She continued, “Don’t you ever, first of all, call me by my first name. You don’t know me. Usually around here, people are referred to as the gentleman or the gentlelady, Mr. This, or That or the Other.” And she explained that’s the way he should refer to her from now on.

Many times these sort of bad first encounters, when two bosses come head to head, it can engender a mutual respect, and in this case with Waters and Montgomery, even a friendship. She wasn’t afraid to tell him the truth about his committee from her lens as a woman and person of color. She made it known quickly that he needed to make certain changes.

There were 55 staff positions and she was the first Black person?Gurl, Auntie Maxine came down on him like your mama when she discovers the mess you’ve been hiding in your room and she pays the rent; to her, his blindspots were ridiculous. One great thing about Auntie is that she goes into these situations and she’s able to see them for what they are. She didn’t go into his committee as the only Black woman ready to bend and fold according to his will and standards like she’d landed there because she held some lucky lottery ticket.

No. She worked her butt off to get in the room. Instead, he would bend and fold to her. At the next meeting (no she did not wait longer, what are you thinking?! This is Auntie Maxine) she told him that she found it really freakin’ strange, actually baffling, that he was chairing a committee for veterans and there was not a Black person in the room till she got there.

After all, there are millions of Black men and women sacrificing their lives and time with their families in these wars, the Persian Gulf, Vietnam . . . Where are the brothas and sistas, bruh? Black people are veterans too. There were 55 staff positions and she was the first Black person?

Auntie Maxine called it out on day two, sister. You don’t need to wait.

Of course, there was more stuttering, she said. “He made some excuses. He told me that he had one minority on the staff one time and he drowned; he died. Then he told me that he had tried to get one to come up from Mississippi and he didn’t want to come there. I said there are plenty of African Americans here in Washington, DC.”

OH. MY. GOD. He couldn’t find someone alive and Black in? These are the “excuses” about the lack of diversity in most American corporate offices, committees, boards, and so on that Auntie Maxine does not have any time for—she does not accept it— and we shouldn’t accept it either.

Waters wasn’t there to fight. She was there to make change. Someone had to say it to this man, but no one had been at the table to do it. Here she was. Ready for it.

So, in the end, he basically went out and found some Black people (yes, they were right there, after all!), and the committee became more diverse than ever. All thanks to Auntie Maxine, of course.

__________________________________

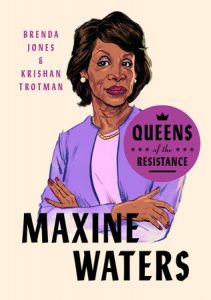

From Queens of the Resistance: Maxine Waters by Brenda Jones and Krishan Trotman, with permission from Plume, an imprint of Penguin Publishing Group, a division of Penguin Random House LLC. Copyright © 2020.