From the Fall of the Towers to Building Anew

Joe Woolhead on Documenting the Chaos of 9/11 and Later Efforts to Rebuild

In 1990, I had arrived in the United States for the first time, settling in New York with a couple of hundred dollars and a dream and the determination to become a filmmaker. I had no green card; like a lot of Irish immigrants, I came into the country on a holiday visa. The first year in the city, I took any work to simply survive. Jobs such as busboy, mover, and casual laborer kept me going. In 1992, I received my green card. This gave me the opportunity to find steadier work as a plasterer and a mason. Nothing like cement to keep my future solid, my dream smoldering, and my belly filled.

Then the “Year of the Nightmare” happened, a turn of phrase my mother used to refer to 1996. A tragic family event unfolded in February of that year, when my brother Brendan was a passenger on a London bus that was blown up by the IRA. Being Irish and incoherent due to his injuries, he was initially under police guard and handcuffed to his hospital bed. In the meantime, his name and his likeness were plastered all over the media, accusing him of being an IRA terrorist. With the help of a civil rights lawyer, the English authorities conceded that such accusations against my brother were groundless. Brendan was exonerated, but in October of the same year, he sadly passed away.

On my return home to Dublin for the funeral, I told my parents about my own near-fatal accident. On May 3rd of that nightmarish year, my legs were severely crushed by fallen granite slabs at a job in the mezzanine level of the Chase Bank headquarters not too far from the Twin Towers. Apart from my leg injuries, I sustained multiple other injuries, which would take seven years of operations, pain management, and therapy to sufficiently recover from to resume work.

In the meantime, I applied for a film course at Hunter College and was accepted in 1998. I had hoped this degree would help me to brush up on my filmmaking skills, acquired in Ireland back in the eighties. Going back to structured study also spurred on my creative endeavors fueled by my love of photography and poetry.

*

On the morning of September 11th, I was living in Corona, Queens, having breakfast in a room not big enough to swing a camera when I heard on the radio that a small plane had crashed into one of the Twin Towers. In those few minutes wondering whether this was an accident or a terrorist attack, I was transported back to that horrible year when my brother died and I was practically crippled for life, and I thought about my life before and after that time, what might have been, wishfully imagining sometimes that the bombing had never even happened, much like the way my mind whirred now whenever I heard of any bombing and I would imagine the wasted potential, the wasted dreams of all those lives lost. Then I heard another plane had hit the second tower. I grabbed my camera, my trusty Canon AE-1 Program that my eldest brother, Gerard, had bought for me in San Francisco in 1982. I headed for the subway. I got out at Sunnyside, where I picked up ten rolls of film in a 99-cent store with my last $10. I got back onto the number 7 train, stuffing the film rolls into my right pocket so that I knew, when one roll was shot, I simply transferred it to the left pocket.

In 2001, cell phones weren’t in widespread use, so when I boarded the train, I noticed half of the people in my carriage were oblivious to the terrifying events that had just occurred in downtown Manhattan. There were other passengers who were staring out the window aghast at the black, smoldering holes in the distant towers. I thought of the lines from Yeats’s poem “Easter, 1916”—“All changed, changed utterly: A terrible beauty is born”—and thought of the hard new reality the entire world was about to confront.

September 11, 2001 – New York. Joseph Woolhead.

September 11, 2001 – New York. Joseph Woolhead.

I photographed the towers from the front window until the 7 train went underground. I transferred at Times Square and went as far south as the subway could safely go, to the stop at Canal Street, then ran the rest of the way to downtown Manhattan as dazed crowds traveled away from the towers burning in the near distance.

September 11, 2001 – New York – Smoke pours from the World Trade Center complex following a terrorist attack September 11, 2001. PHOTO CREDIT: Joseph Woolhead / SIPA PRESS

September 11, 2001 – New York – Smoke pours from the World Trade Center complex following a terrorist attack September 11, 2001. PHOTO CREDIT: Joseph Woolhead / SIPA PRESS

What I witnessed that day, and on subsequent days, can be seen in the photos of people fleeing, the injured bodies, the firefighters running toward the fires, the second tower collapsing, the Winter Garden an unrecognizable flaming wreckage, the collapsed interior of Tower 6, the evening sun over a still-burning ground zero, and frightened, furious faces everywhere I looked. My experience is harder to explain. I’ll never forget the feeling of loss and dread, and bitterness and anger welling up inside me during those three days I spent there shooting and how super-real or hyper-real in a visceral sense everything seemed.

September, 11, 2001 – New York – Rubble near the base of the World Trade Center complex following a terrorist attack September 11, 2001. PHOTO CREDIT: Joseph Woolhead / SIPA PRESS

September, 11, 2001 – New York – Rubble near the base of the World Trade Center complex following a terrorist attack September 11, 2001. PHOTO CREDIT: Joseph Woolhead / SIPA PRESS

*

In 2002, I returned for the first anniversary to pay my respects. Somehow, I was funneled into the crowd of mourners, first responders, and security who walked down a massive construction ramp into the foundation area 70 feet below street level. Clouds of dust swirled in gusts around the mourners as they converged on an enclosed ring area where flowers were being tossed and prayers were being said. Soon, there was a sea of colors at the center of the site. Truly, on that terrible day of remembrance, all of us wept for our losses.

Two years passed. My old roommate and friend Dara McQuillan called. He was working with Silverstein Properties, the chief developer of the WTC site, and he needed some photographs of the July 4th groundbreaking ceremony for the Freedom Tower. Ultimately, Dara would ask me to document Silverstein’s efforts to rebuild the World Trade Center full-time. I knew this opportunity was a once-in-a-lifetime shot to capture the building of a new World Trade Center.

I became obsessed, driven by the idea that the prevailing narrative of the World Trade Center as a place of doom and gloom could be transformed, that people’s perceptions could be altered by the visuals of the progress of work at the site and that ultimately, seeing my pictures in the news, people would see progress and construction where the old towers used to be, and they would be made aware of the great changes happening on the ground and high up above the restless city streets as steel and concrete were riven together into spectacular form and new towers were seeded into New York bedrock.

I began to latch on to this notion of getting the “big picture” by making many, many pictures and building a mosaic of images that would incrementally showcase the progress of work on-site. I would even imagine this “big picture” as a visual superstructure with the elements or materials made of images, yet, unlike a building, which is solid, my vision would mutate as the real buildings continued to rise around me, floor by floor, conquering space. Another analogy I played with was the notion of a thousand photographers scrambling all over the site and still not being able to cover the multiple critical steps in the development of this complex of buildings.

*

In the fall of 2006, I was hired by Esquire to travel to a shipyard in Virginia and photograph steel arriving from Rotterdam that would serve as the first columns for One World Trade Center. I met Scott Raab in our hotel lobby, two minutes late for our appointment. He huffed audibly and gave me a look that made me feel like a circus flea. He asked me if I was serious about my work as we raced to meet the incoming ship. With minutes to spare, we made it before the ship docked and unloaded its priceless cargo.

While I went below deck to capture the workers rolling off the steel pieces, Scott went to interview the captain. At one point, I stumbled into the captain’s quarters unannounced, cutting off Scott midquestion, and he gave me his second withering look of the day. In his next essay, he immortalized me as “the putz with the camera” who barged in on his interview with the good captain, and I was sure that was the end of our brief partnership. Still, I’d never felt so honored, being cursed out in print.

I became obsessed, driven by the idea that the prevailing narrative of the World Trade Center as a place of doom and gloom could be transformed.

Thankfully, as the months progressed and the foundations began to come together creating floors where there had only been bedrock, Esquire called again. This time, I drove with Scott to Banker Steel, a mill in Virginia that was fabricating the raw steel shipped from Europe. The factory was mesmerizing—all the sights and noises and smells pervading the place. Soon after that trip, Scott invited me to his house in New Jersey for dinner, where I met his lovely family. I ended up staying late, having one of those rare kitchen conversations that go deeper than you meant to go, but when you go that deep, it turns out to be all right, comforting somehow, because you’re in great company. We talked a lot about life, and all that it entails to keep things together and to keep on—exactly what he was writing about in his stories about the World Trade Center.

*

The years passed. The buildings grew up, conquering space, conquering blue sky.

I had developed a strong rapport with the workers on-site. My background in construction put me in good standing with the crews. Since I was visiting the site so much, one of the ironworkers jokingly referred to me as the “the mayor of the World Trade Center.” Being at ease with the workers was crucial. It gave me the freedom to move naturally with the workflow and without disturbing them. Having been injured on the job, I understood the hazardous nature of construction and the importance of minding my own business.

Sometimes, that was easier said than done.

Even though I was officially working for Silverstein Properties, I was still closely watched by site inspectors. I felt like I had a target on my back after being kicked off several times for known and unknown offenses. Fortunately, Dara would smooth things over with the authorities and I would be back shooting in no time. I always managed to fight my way back on-site. Still, there was one time when I thought I would never get back on-site, and that was after I captured the photograph that graces this book’s cover.

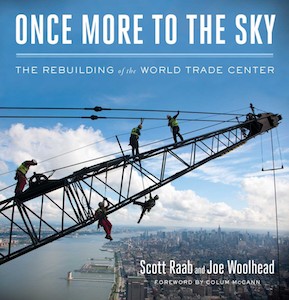

In 2012, with almost 100 floors complete of the new WTC, Esquire asked me to get a video for their new social media page, a defining image that was shot within the building itself and captured both the frame of the building and the city beyond. It wasn’t an easy request. I spent weeks trying to figure out the right shot. Then, one beautiful morning, on the 90th floor, I encountered a supervisor who showed me the shot he had just taken with his flip phone of a crane inspector hanging off the boom of the “slider” crane attached to the side of the building. It was exactly the shot I was looking for.

I raced up to the 92nd floor for a better view. I ripped away the protective netting on the outside staircase and set up my shot, recording five workers on the crane as they inspected the steel struts for any damage from lightning strikes the night before. After several minutes recording, I had the foresight to shoot four or five frames and then continue recording. The cover shot of this book is one of those frames. Subsequently, the image went viral and took on a life of its own. Ever since, people who see my image have made this unconscious connection to the iconic photograph Lunch Atop a Skyscraper (1932) by Charles C. Ebbets, of workers having lunch on a steel beam during the building of Rockefeller Center. Funnily enough, even though I’m the one who shot the photograph, I just can’t see the connection between them. Later, I was even interviewed for a documentary, Men at Lunch, about the famous photograph, and I still didn’t see the connection!

Unfortunately, as this minor visual triumph was happening in my life, I got the call from the Port Authority that I was barred from the site. I was devastated. I was never given a clear explanation for why they chose to bar me. One excuse they offered was one of the workers pictured was not safely tied off, but that was clearly untrue. It would be over six months before I was granted access again.

After getting back on, I continued to photograph at a furious pace until I had amassed a trove of images—nearly three million. As work continues on completing the WTC master plan, that shot number is still growing. And I still imagine the “big picture” coming into focus as the city rises again.

__________________________________

Excerpted from Once More to the Sky: The Rebuilding of the World Trade Center. Used with the permission of the publisher, Simon & Schuster. Copyright © 2021 by Scott Raab and Joe Woolhead.

Joe Woolhead

Joe Woolhead was born and raised in Dublin, and has been living in New York City for over thirty years. When the attacks happened on September 11, 2001, he grabbed his camera and shot what he witnessed over the course of three days. His work has since been featured in the New York Times, Esquire, the book A Century Downtown, and the documentaries Men at Lunch and The Irish New Yorkers.