When I was ten years old, I broke my mother’s wooden cutting board. I can’t remember how it happened; I’m sure it wasn’t on purpose. I’m not a psychopath. But regardless, in that moment both the cutting board and my life split in two. This went down at the end of fifth grade, and it couldn’t have come at a worse time. Summer was a nightmare scenario: three long, hot months with a punk-ass kid (that was me), a drama queen (that was Tatiana), a boyfriend (that was Westley), and an overworked matriarch (Mom) packed into a one-bedroom apartment on Pelham Parkway in the Bronx. Everything in our house was cramped. You could literally see and hear everyone else from every corner. The four of us fought for turf like we were in a prison yard. My mother and Westley slept in the living room; Tatiana had claimed the bedroom as her own. Now a sign on that door read Keep Out, and if I wandered in, she’d smack me so hard my ears rang for days. Tatiana hated Westley and me; I wasn’t a fan of hers, and gave Westley a harder time than I should have. We all loved my mom, but between her job at Café Lou’s and catering, she didn’t have that much time for any of us.

Without a bedroom of my own, I slept in a closet. Not a closet-sized bedroom, an actual closet. There was just enough room to wedge a twin mattress on the floor with a few extra inches on one side. To my mother’s credit, she tried to make it room-like. She cleared out the clothes racks and shelves, decorated the walls with posters I got to choose, and installed a moon-shaped nightlight since I was terrified of the dark.

For a while I loved it. It was like being in a hobbit hole. But by the time I was ten, what had been comforting and snug felt like a cell. I was speeding into adolescence, with the usual haywire emotions. I needed a space of my own. More space. It couldn’t be at my father’s apartment, just twenty minutes away, at 233rd Street and Amundson Avenue. The weekends I spent with him left me feeling even more claustrophobic than my time in the closet. At least the closet was my own. At my dad’s house, every single thing I picked up or put down or sat on or lay on, every task I tried to complete, could set him off on an epic rage. An eye roll would “earn” me a beating with the African whip. When I returned to my mom’s on Sunday nights after a weekend with him, with bruises up and down my arms and legs and a body full of hurt and rage, I’d throw myself in my closet and lock the door.

No wonder I fought with everybody over everything. Tatiana and I constantly skirmished, over what to watch on TV, who showered first in the morning, on and on. These were nasty, hair-pulling fights, and since my mother was often at work, they lasted for ages. When she was home, I fought with my mother over my tone of voice, her tone of voice, why I was stuck in a damn closet, why she was never around anymore, and why I kept getting into trouble.

As I morphed from a fat-cheeked kid to a young man, the world began to see me differently. At Mount Saint Michael, the Catholic private school to which I had transferred, I was surrounded and befriended by much tougher kids, mostly black like me, many of whom had grown up fending for themselves. Many of the teachers, however, were middle-aged or older white women, and they approached us—ten-year-olds—like we were dangerous. They wielded their power like prison wardens. And in their fear I saw reflected back an image of myself I hadn’t seen before. At the same time I saw the power my friends possessed, how they could manipulate using fear. As our teachers reprimanded us and, when that didn’t work, suspended us, I saw how the kids around me dealt with this anger and frustration. They turned their faces to stone and deadened their eyes like those of statues. They became hard and menacing, and as I saw it then, that hardness meant strength.

My mom said I had to learn respect; I said she couldn’t control me. Both were true.At home if I broke a video game cartridge, when West tried to talk to me about responsibility I’d retort that he had nothing to teach me, that he wasn’t my dad. At ten years old I’d come home after the streetlights had switched on, smelling of the Newport Lights I had tried to smoke and sometimes high, and challenge West and my mom to say something. I started to hang a red bandana out of my back pocket like I was a junior member of the Bloods (of course I took it out and carefully stashed it in my bag before I went out into the streets). I welcomed any pretext for a brawl. West, who had gotten in trouble himself as a kid and could see some of himself in me, would back off and off until he couldn’t back off any more. And then we’d fight, as my mother looked helplessly on. A few times he’d slap me around the small kitchen, more out of frustration than rage, but it hurt just the same. Every time we had an argument like that, it was like a slipknot that cinched a bit tighter in the apartment.

The cutting board was the last straw. Soon the fight just became the same one we’d been having for months. My mom said I had to learn respect; I said she couldn’t control me. Both were true. That night I stormed into the closet and slammed the door again.

*

I awoke the next morning to the smell of bacon frying. No matter how rough the week had been or how much we had scrounged for money or how hard we fought on Saturday night, Sunday morning was a chance for our family to hit reset. My mom cooked pancakes until they were perfectly golden brown and fried strips of bacon until the aroma of hot fat filled the kitchen. She turned cans of salmon into little patties we pan-fried together. I loved helping her make scalloped potatoes most of all. She minced the garlic and onions and sliced the potatoes while I layered them in a casserole dish and tended the garlic and herbs as they softened in a hot pan. We never fought in the kitchen. It’s hard to, when you’re standing side by side at the counter.

West was the egg master and could make eggs like a short-order line cook, any way you liked them. Tatiana, who by this time was attending a Food and Finance High School, bustled around the small space in a cloud of cake flour. When she asked, I fetched her baking powder and salt without complaint, a rare period of cooperation.

In the first few seconds of getting up, I forgot about the cutting board. But as soon as I walked into the kitchen, I remembered. Something was off that morning; I could feel a heaviness in the air.

“What’s wrong, Ma?” I asked.

With no preamble she said, “You’re going to live with your grandfather.”

At first I was confused. Which grandfather did she mean? My real grandfather, her dad, Bertran Robinson? That couldn’t be right; she hardly knew him herself. I had met him a few years ago when we had visited him in the galley of a ship where he worked as a cook down in Beaumont, Texas. He had towered over me like an old statue, smelling of fry oil and diesel fuel. Later he had made me fried crawfish and fried shrimp that I ate with my feet dangling in the air off the wooden planks of the dock, looking at the water below. But that was the last I had seen of him.

Maybe she meant her stepfather, a laid-back Trinidadian guy named Winston who lived in Virginia with her mother. We were very close, but that was unlikely too, since we all called him Papa.

“No,” said my mother, “with Granddad.”

“Granddad!” I yelped. “But he lives in Africa!”

“Yes, I know that,” said my mom. “You’re going to live there with him.”

“When am I leaving?” I asked.

“We’re leaving for D.C. this afternoon,” she said. “You’ll fly to Lagos from there.”

“How long will I be gone?” I asked.

She paused for a moment. “Just for the summer.”

*

I loved my grandfather of course. I saw him nearly every summer when he returned from Nigeria to spend time with Auntie Chu-chu at her home in Washington. Not only were my grandfather and my father not close, but Auntie Chu-chu was the eldest, so by tradition she had the right and obligation to host him. Every August all of us New York cousins would pile into a car and head south to D.C. That part of the trip wasn’t out of the ordinary. But I hadn’t been to Nigeria since a week-long trip with my father five years ago. I couldn’t tell whether this was retribution in some way for the cutting board or whether it was just a long-planned childcare solution for the summer that no one had thought to tell me about.

At any rate, the sweetness of breakfast was gone. Soon after, I packed up my few belongings—I had, after all, only a closet. That afternoon I gave Westley a hug before my mom and I began the drive south. I was scared and a little apprehensive, but Africa was cool, if far away, and I was excited to spend time with Granddad.

My grandfather was born in Zaria, in northern Nigeria, but his family hailed from Ibusa, a village in the Delta State that was the cultural center for the Igbo people. Though he studied in Lagos as a kid, most of his adult life had been spent in the States. From the 50s through the 70s, he was a leading academic voice in the Pan-African movement, holding teaching positions at Howard and Fisk Universities, and publishing books on black ideology, on the diaspora and African identity and Black Liberation. But he saw firsthand the assassination of his friends like Stokely Carmichael, and concluded that the government wouldn’t let black activists live in peace until they were either in the ground or in a cell. In 1973 my grandfather realized he could never be free, truly free, in the United States. So he moved back to Nigeria, leaving behind his wife, my grandmother Gloria, and his seven grown children, including my father and Chu-chu.

My grandfather first settled in Lagos, where he served as the director general of the Nigerian Institute of International Affairs. But by the time I was sent to live with him, he had returned to Ibusa and assumed the title obinzor, or elder. He had built himself a large compound, with a couple of wives and a flock of chickens and a ceremonial hall in which he held court. That we came from noble blood was part of the family lore, I knew it well. In fact, every time we saw him in D.C. he made all the male cousins recite, “As men we must be honorable, respectful, and gentlemen. We must take care of those around us.”

When he opened the door of my Aunt Chu-chu’s house that evening, my grandfather certainly looked like something out of a history book. He wore a long white embroidered shirt called an isiagu and matching silken pants. On his head was a traditional red fez. His face bore the creases of age, his eyes crinkled behind a pair of wire-rimmed glasses and his thin and sinewy arms poked out of his sleeves. He was so foreign-seeming, so . . . African. But his smile was warm as he hugged my mother, and when he hugged me, I hugged him back.

__________________________________

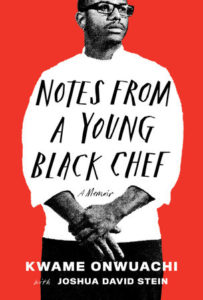

From Notes from a Young Black Chef by Kwame Onwuachi with Joshua David Stein. Used with permission of Knopf. Copyright 2019 by Kwame Onwuachi and Joshua David Stein.

__________________________________

Co-authored by Joshua David Stein. Joshua David Stein is a Brooklyn-based author and journalist. He’s the editor-at-large at Fatherly and the host of The Fatherly Podcast, the coauthor of Food & Beer, the U.S. editor of Where Chefs Eat, and the author of the children’s books Can I Eat That?, What’s Cooking?, and Brick: Who Found Herself in Architecture. He was the restaurant critic for the New York Observer until he quit in protest in 2016, and a food columnist for The Village Voice, before that went mute.