From Star Wars to Lord of the Rings, How to Build a World

The Art of Making the Imaginary Seem Real

For geeks, 40 years after Star Wars, it is no longer enough to make a world of fantasy; one must make a world. World-building has become the essential foundation of geek artworks, so much so that in 2013, the science fiction author Charlie Jane Anders called it “an essential part of any work of fiction”(!), and “the lifeblood of [science fiction and fantasy] storytelling.” In order to appeal to geeks, fantasy artists today are obliged to create not just movies, novels, or comics, but entire fictional cultures, languages, species, landscapes, histories, mythologies—sprawling alternative earths, strange other places that can be described so confidently and so thoroughly that their flora and fauna and machinery seem as solid and convincing as our own.

But world-building is hardly a new concept. Long before Harry Potter, long before Star Wars, philosophers and scientists had already created the intellectual practice of world-building, a kind of thought experiment in which one invents a fictional world in order to test abstract concepts. For instance, Immanuel Kant used world-building in the late 1700s to make ethical arguments. In a famous example, he proposed that one has a moral obligation to repay loans, because if everyone chose not to repay, then the result would be a world where no one ever lent anyone money. Scientists since then have used world-building to see how natural laws might work, whether real or imaginary—for instance, what other planets might be like.

By the late 1850s, a fictionalized version of this practice had split off from philosophy and the sciences, becoming science fantasy, then modern science fiction literature, resulting in works like Edwin Abbott Abbott’s Flatland: A Romance of Many Dimensions. That novel, first published in 1884, is many things, including a satire of Victorian social customs. But it also imagines different dimensions in order to demonstrate concepts of space and time, telling the story of a square that inhabits a two-dimensional world (Flatland), but winds up visiting a one-dimensional world (Lineland), then meets a sphere from a three-dimensional world (Spaceland).

The physicists on Big Bang Theory are passionate fans of sci-fi, and in that sense, little has changed since the Victorian Era. There has always been a great deal of crosspollination between science and science fiction. In his 1920 volume Space, Time and Gravitation, Sir A.S. Eddington, Plumian Professor of Astronomy and Experimental Philosophy at Cambridge, tries to explain how moving in spherical space might cause distant places to appear frozen in time. To help the reader envision this, he appeals to the “fantastic world-building” in a 1901 story by H.G. Wells, “The New Accelerator,” in which a fantastical drug allows a person to live and move so quickly that the rest of creation seems to crawl to a halt. Indeed, for many geeks, the whole purpose of science fiction is the illustration and explanation of scientific concepts.

Prior to Lucas, the most famous world-builder was probably J.R.R. Tolkien, who celebrated the practice in his 1939 lecture “On Fairy-Stories.” There he defined and defended fantasy literature as being stories about other realms—“faerie,” or “Secondary Worlds”—via which authors and readers engage in imaginative and linguistic play. Just as in the case of science fiction, these stories create realities other than our own, enchanted realms where the sun might be green instead of yellow. Tolkien defended this practice on practical grounds, claiming that it allowed us to refresh our perception of reality. Essentially, reading fantasy lit allows us a break from the everyday, the chance to go on a mental vacation, after which we return to the real world and see it anew. Tolkien further argued that in order for this experience to succeed, in order for faerie to be able to work its magic, the secondary worlds must be credible enough that we fall completely under their spell, to which end authors must give them “the inner consistency of reality.”

Tolkien delivered his lecture right after he started work on the sequel to his popular 1937 children’s book The Hobbit. Today we know that sequel as The Lord of the Rings. Rather than writing “The Hobbit, Part 2” as his publisher originally requested, Tolkien expanded his quaint children’s tale into an epic account of a war involving hundreds of characters. To do so, and in order to illustrate his ideas about fantasy writing, he devised an elaborate mythology of the “Secondary World” of Middle-earth, complete with its own geography, plus detailed accounts of all its peoples: humans, Elves, Dwarves, Orcs—and Hobbits.

“In world-building, there isn’t any supernatural, not really—just a different order of the natural.”

In doing so, Tolkien updated the concepts of fairy tales. Those stories traditionally depict fanciful species as needing to abide by peculiar rules. Fairies can’t tolerate the feel or sound of cold iron, and brownies will flee if you reward them for their work. Holy water and crucifixes repel vampires, and only silver bullets can slay werewolves. But Tolkien, being an Oxford professor of language and literature, went much further than any of that, creating respective kingdoms with lineages and histories and dietary norms and architectural preferences—and languages. Which is to say, he made his fantastical cultures more like human cultures, the same way that Lucas made spaceships more like cars. Tolkien went so far, in fact, that not even The Lord of the Rings and its appendices could contain all his world-building, which is why his son Christopher was able to collect and publish, four years after Tolkien’s death, The Silmarillion, a multivolume “backstory” that reveals that the Quest to destroy the One Ring was but one event in an epic struggle lasting thousands of years. (It involves magical jewels.)

Through world-building, geeks redefine the supernatural as the product of alternative natural laws that are themselves subject to discovery and documentation via the tools of science and reason. Which is to say, in world-building, there isn’t any supernatural, not really—just a different order of the natural. Dwarves and elves, planets where time runs backward, self-aware computers that go rogue and murder astronauts—all these things and more can be posited via world-building, an elaborate game of “what if?” that gives those fantasies and others their time in the sun, where they’re treated as something real, beings and objects as mundane as umbrellas and batteries, as normal as earthworms and pots of coffee.

For philosophers and scientists, and for Tolkien, worldbuilding had a practical function, and some still use it that way today. But many engage in world-building now for purely artistic reasons, or simply because it’s fun. Humans have always felt compelled to imagine things that aren’t real, then devise elaborate mythologies around them—hence the elaborate pantheons that define so many religions past and present. Geeks differ from mystics, however, in knowing that their invented worlds aren’t real, even as they want their fantasies to seem as real and as believable as possible.

The geek mantra might prove the same as the tagline for The X-Files: “I want to believe.” What makes the game they’re playing engaging and challenging is the inherent tension in making the imaginary seem nonimaginary. What does a blue whale look like? One can just go look. But what does a dragon look like? Ah, that presents a problem. Since dragons don’t exist, and never will exist, one is forced to dream up an answer. The challenge for geeks, then, is to produce an illustration or a movie that looks as convincing as the blue whale does when drawn or photographed, as well as to explain what impact a dragon would have on its environment, from the food chain to the local economy.

Lucas absorbed the tenets of world-building from the fantastical works that he adored as a child, including his beloved Flash Gordon, which featured its own strange Martian species, such as the Clay People and the Forest People. Edgar Rice Burroughs’s John Carter of Mars and Frank Herbert’s Dune are other clear influences. So when Lucas couldn’t get the rights to Flash Gordon, and decided to make his own version, he imagined not only a fast-paced adventure set in space starring Luke and Han and Leia, but an elaborate backstory—his own batch of world-building. Lucas’s biographer Dale Pollock reports that even in the first treatment of Star Wars, finished in May 1973, every “person, beast, and structure was explicitly named and described in detail.” Lucas worked out detailed histories and cultural traditions for the Wookies, as well as all of C-3PO and R2-D2’s owners. This wealth of material eventually proved far too much for a single film, leading Lucas to cut his treatment in half, then into thirds, finally focusing on the middle third, the portion that would become, in 1975, recognizable as Star Wars.

But Lucas retained his ambition of telling a larger story, a saga, which is why he went on to make two sequels as well as the prequel trilogy. Along the way, he also toyed with making smaller spin-off films that would showcase the elaborate world that he’d created: a movie with nothing but droids, and another with nothing but Wookies, speaking their native language. (Lucas initially conceived of Luke’s Uncle Owen and Aunt Beru as anthropologists studying the Wookies.) Indeed, it’s possible that the concept of a Wookies-only movie served as the basis for three later works for television: the 1978 Star Wars Holiday Special, the 1984 Caravan of Courage: An Ewok Adventure, and the 1985 Ewoks: The Battle for Endor (Ewoks being a diminutive version of Wookies). This ambition might have also fueled the animated Ewoks and Droids Adventure Hour, broadcast from 1985 to 1986.

“Humans have always felt compelled to imagine things that aren’t real, then devise elaborate mythologies around them—hence the elaborate pantheons that define so many religions past and present.”

All of these TV programs are instructive, offering insight into what Star Wars might have looked like minus its New Hollywood realism. The Star Wars Holiday Special, for instance, is thoroughly fake-looking, having been shot quickly and cheaply on obvious television soundstages, using shoddy costumes and makeup. It’s also bewilderingly episodic, emphasizing older TV guest stars like Harvey Korman, who does a manic Julia Child impression, instructing Chewie’s wife, Malla, on how to prepare “Bantha Surprise,” and Bea Arthur, who turns out to own the Mos Eisley Cantina, where she sings a cabaret number. Over two tedious hours, we’re treated to colorfully decked-out acrobats, a sultry serenade by Diahann Carroll, vaudevillian improvisation, and cartoonish matte paintings that look like paintings, not actual treetop Wookie homes. At one point, Jefferson Starship turns up, presumably because the band has starship in its name. All of which is to say, that while the Special features world-building—we meet Chewie’s family conversing for long stretches in their native grunts and growls while romping about their cozy tree house on Kashyyyk as they prepare to celebrate a holiday known as “Life Day”—it’s much more like a bad late–seventies variety show than it is like A New Hope.

Star Trek’s original TV series is similarly instructive. There’s no doubt that from its first appearance in the 1960s, Star Trek was deeply committed to world-building. Episodes frequently saw Kirk and his crew reach regions of space where the laws of physics got turned upside down, and the design of the USS Enterprise was anything but arbitrary. Its designer, Matt Jefferies, who was a pilot, based the ship’s designation, “NCC-1701,” on aircraft registration codes, and angled the twin sweeping nacelles away from the rest of the craft with the logic that they project their warp field backward, allowing the ship and its crew to ride in front of it. The ship’s layout is similarly logical, its sections defined and mapped out in relation to one another. When Kirk and the others ride the elevator-like Turbolift from engineering to the bridge, for instance, their car’s pulsing lights and corresponding sound effects indicate each time it changes direction, running first horizontally, then vertically, then horizontally, then vertically again.

Star Trek also regaled its viewers with an expansive mythos of alien worlds and species. While many of those aliens were obvious metaphors for rival nations involved in the Cold War, and depicted with little more than simple prosthetics and face paint, the Vulcans, Klingons, and Romulans each possessed unique anatomies and physiologies and psychological profiles, not to mention unique languages, histories, calendars, and mating customs. Being a lifelong fan of Star Trek, I know that Vulcans have green blood, a heart where a human liver is, and no appendices, while Klingons have reddish-pink blood and multiple organ redundancy (which even has a Klingon name: brak’lul). Vulcans also mate every seven years, in a ritual known as pon farr, while Klingons—well, let’s just say it gets intense.

But while Star Trek featured oodles and oodles of worldbuilding, it’s remembered just as much today for its cheap sets and cheesy special effects, not to mention its melodrama and heavy-handed allegories. While many of its episodes are undeniably classics, a fair amount of the show was always hokey. Even a brilliant episode like “The City on the Edge of Forever,” which is gripping, dramatic television, includes an alien planet with obviously fake rocks, a city with obviously fake streets, and a delusional Dr. McCoy with obviously fake “disease” makeup plastered all over his face.

As we’ve seen, in making Star Wars, Lucas brought New Hollywood realism to bear upon the science fiction practice of world-building. The result is especially evident in the movie’s cantina scene, a favorite of many a geek. Before that scene, which starts about 45 minutes into the film, we see Jawas and droids, as well as Tusken Raiders. But it isn’t until Luke journeys with Ben Kenobi to Mos Eisley, a “wretched hive of scum and villainy,” that we truly get a sense of the scope of the galaxy that Star Wars represents. Stepping into that bar, our eyes adjusting to the light, we, like Luke, are overwhelmed by the sheer number of weird aliens on display, from creatures that look like werewolves and horned devils, to sultry twin ladies in long braids, to a dwarfish bat thing chirping for more booze, to a hammerhead-like beast decked out in a robe, all of them jabbering in foreign tongues, quaffing drinks while kicking back to space-age jazz. Star Wars boldly and confidently presented its viewers with a secondary world (à la Tolkien) with more inner consistency than ever seen before—a more convincing vision of fantasy, Flash Gordon “done very well.” The achievement of Star Wars, then, as far as geeks are concerned, is that it opened the gateway to reimagining all science fiction and fantasy in the same way.

Which is what they’ve been busy doing ever since.

__________________________________

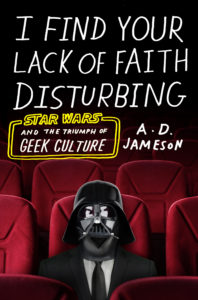

From I Find Your Lack of Faith Disturbing: Star Wars and the Triumph of Geek Culture. Used with permission of Farrar, Straus and Giroux. Copyright © 2018 by A.D. Jameson.

A.D. Jameson

A. D. Jameson is the author of several books, including Cinemaps, a collaboration with the artist Andrew DeGraff. His most recent book is I Find Your Lack of Faith Disturbing. A former blogger for HTML Giant, his fiction has appeared in Conjunctions, Denver Quarterly, Unstuck, and elsewhere. He is a PhD candidate in the Program for Writers at the University of Illinois in Chicago.