From Pick-Up and Pynchon to a Lifetime in Publishing

Gerry Howard and Peter Kaldheim on a Friendship Borne of Books

Longtime friends Gerry Howard and Peter Kaldheim discuss how they bonded over their great love of books and how their friendship helped them carve their respective paths in the New York literary world.

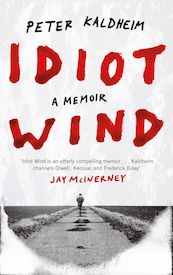

An executive editor and vice president of Doubleday Books, Howard is notable for publishing the first two books of David Foster Wallace, while Peter Kaldheim first entered publishing as a copy editor at Harcourt, then as an acquiring editor at Van Nostrand Reinhold. Kaldheim’s memoir, Idiot Wind, will be released from Canongate on August 1st, 2019.

*

Gerry Howard: So let’s set the scene here. It’s the summer of 1971 and we’ve just finished some three-on-three pick-up games on the courts in Shore Road Park in Bay Ridge at 79th Street. I’m back at home with my folks awaiting/dreading my senior year at Cornell, where I am majoring in English, with no plans whatsoever as to what I might do come graduation. You are new to the park and I’ve been impressed with the accuracy of your bank shot. So we begin to talk, and then, improbably enough, the subject of Thomas Pynchon comes up—a first, not just for that park, I’m sure, but perhaps the entire neighborhood.

Peter Kaldheim: That’s right. I had read Pynchon’s The Crying of Lot 49 as one of the assigned texts in a course on Postwar American Fiction during my just-completed senior year at Dartmouth and immediately became a Pynchon fan. I knew that Pynchon had attended Cornell, your alma mater, and that’s what prompted me to ask you if you’d read his work. I believe I also brought up Richard Farina’s Cornell-based novel, Been Down So Long, It Looks Like Up To Me.

GH: I was in the midst of my second try at V., which had defeated me once before. But I’d caught on to its narratively open-ended method and was hooked.

Anyway, what impressed me then, and later, was not just your refined and advanced taste in books, which reflected my own nascent impulses in so many ways, but also that you knew actual facts about actual writers. Such as that Pynchon had been a Cornellian and that the idea for One Flew Over the Cuckoo’s Nest came to Ken Kesey during one of his early acid trips at a VA psych hospital. To callow English major me, authors were godlike and remote and sort of theoretical. But then, you were a writer yourself.

PK: I didn’t read V. until after I’d read Lot 49, which I think was fortunate, because it isn’t quite as daunting as V. for a first-time reader of Pynchon. Having had my appetite whetted by Lot 49, I found it easy to fall in love with the convoluted plot twists and esoteric historical references that Pynchon built into his debut novel, and I had no trouble getting through it on my first try.

It’s true that I’ve always enjoyed collecting tidbits of information about the lives of writers I admire, and I suppose that’s because, as a would-be writer myself, I had a lot of curiosity about the way writers work and live (although, in Pynchon’s case, public information about his private life is famously scarce—but I do remember being pleased to discover that, like me, Pynchon grew up in the Long Island suburbs).

GH: As I was later pleased to discover that Don DeLillo and Robert Stone, both writers of great importance to us, had both been Catholic boys from the New York City area.

So it was off to the literary races for us. The period from the late sixties through the seventies was a great time to be an adventurous and ambitious reader, especially of “advanced fiction.” You were a terrific guide through this sometimes daunting territory. It was high season for the cohort of writers I think of as the Great White Postmodernists. A partial list of this school or tendency would include William Gass, Donald Barthelme, John Barth, John Hawkes, Robert Coover, and William Gaddis (whose huge and uncompromising The Recognitions reached us like a distant rumor from the fifties). Their work was formally innovative, epistemologically destabilizing, black humored, and sometimes crushingly difficult.

I think I was attracted to this work because it gave me an excuse to apply my literary tool kit. On top of that the dark irony these writers trafficked in implied an acute critique of consensus reality, and I was no fan of “la vie quotidienne” (savants will recognize the Barthelme allusion here) at this point, being stuck in an entry-level advertising job of no interest and feeling way low in the water.

The work of the Great White Postmodernists was formally innovative, epistemologically destabilizing, black humored, and sometimes crushingly difficult.

PK: Yes, we were both drawn to American writers who experimented with narrative strategies that challenged the status quo, and one of the real perks of my friendship with you was the fact it gave me someone simpatico to discuss the latest literary trends with, someone who didn’t get a blank look on his or her face when I brought up novels like Stone’s Dog Soldiers or DeLillo’s End Zone. So it was a banner day for me when you left your drudge job in advertising and took up a position as a copywriter at HBJ—lunch breaks in the company cafeteria certainly got a lot more interesting after you came on board.

Speaking of William Gaddis, I had often come across his name in discussions of Pynchon’s novels (e.g., in Tony Tanner’s survey of postwar American fiction, City of Words, but I didn’t get around to reading The Recognitions until I came across a first-edition copy on the shelves of the in-house library at HBJ. I think it took me two weeks to work my way through it, though it was well worth the effort (but a damned heavy book to hold up with one arm while you’re strap-hanging on a crowded subway car).

Keeping abreast of the latest work by the Great White Postmodernists was made easier for the both of us by HBJ’s relative proximity to the venerable Gotham Book Mart, which was an easy crosstown walk west on 47th Street to the Diamond District. I know I made countless lunchtime treks to the Gotham, where the cramped back room was chock-a-block with the kinds of little magazines that would publish cutting-edge work by the likes of Robert Coover and William Gass and Harry Mathews (and where from time to time I’d share the space with an eccentric character dressed in sneakers and a full-length raccoon coat—Edward Gorey).

GH: Yeah, I did a lot of my most important reading on the R train. And the Gotham was the very heaven for bookworms of our bent.

I owe you the world for tipping me off to a job as a copywriter at HBJ. By that time I’d blown on the embers of my notion that I might find work as a trade book editor, and that job was my foot in the door of the publishing industry. Strangely, I was lucky not to have started out, as most editors have, as an editorial assistant. The HBJ job was a 9 to 5 gig, which left my evenings and weekends free to read the books I wanted to read, including skull-stretchers like The Recognitions and Gravity’s Rainbow. If I’d been an assistant that time would have been taken up with reading and reporting on dozens and dozens of as yet unpublished manuscripts of wildly varying quality and interest. Instead, I had the time to discover and hone my own taste with vast and indiscriminate, free-range reading.

One of the real perks of my friendship with you was that it gave me someone simpatico to discuss the latest literary trends with, someone who didn’t get a blank look on his or her face when I brought up Stone’s Dog Soldiers or DeLillo’s End Zone.

DeLillo! Now there was a life changer. I remember you mentioning his novel End Zone with sardonic appreciation of its equivalence between the language of football and nuclear war planning. So I got myself to the Womrath’s bookstore on Third Avenue and bought “pocket books” reprints of that book and Don’s first novel Americana.

I began with the latter and it was love at first sentence: “Then we came to the end of another dull and lurid year.” I had discovered the writer of my life, cool in both senses, and hyperintelligent. I would end up buying all of his subsequent novels in hardcover as soon as they came out, no small outlay on a publishing salary, and the happiest of circumstances conspired to allow me to be Don’s editor on Libra, to this day the most satisfying experience of my career. And for the cherry on top, I persuaded Don to let us reissue Americana as a Penguin paperback.

I’ll toss you two more crucial books that you introduced me to and that I think helped to define our evolving canon, Gil Sorrentino’s Steelwork, the great Bay Ridge novel, and Fred Exley’s A Fan’s Notes, the foundational text in Male Failure Studies. How did you come upon them?

PK: Ah, Steelwork! What a surprise that book was when I plucked it from the shelves at the Gotham one afternoon in 1972, two years after its publication. The taxi-yellow cover, with its photo of a street sign from Fourth Avenue in Bay Ridge, was what caught my eye at first. I had never come across Sorrentino’s work before, but after scanning the first few pages, I knew I had found treasure.

The book’s 96 short chapters, each set between the years of 1935 and 1951, offer a kaleidoscopic portrait of the working-class Catholic neighborhood where Sorrentino (and my parents, who were his contemporaries), grew up—an enclave of Irish, Italian, German, and Norwegian immigrants that was rife with what Sorrentino termed the “fake bitter dignity of the poor, underneath which desperation thrives and writhes.” The dozens of neighborhood characters that populate Sorrentino’s Bay Ridge are as memorable—and as memorably rendered—as the Irish locals that make up the cast of James Joyce’s Dubliners. High praise, I know, but I believe it’s justified, and I was delighted when Dalkey Archive Press decided to reissue Steelwork in 2012, and even more pleased that they chose you to write the Foreword to the new edition. Here’s hoping it stays in print forever!

Fred Exley’s A Fan’s Notes (the second great love of my reading life, after Jack Kerouac’s On the Road) was recommended to me by my friend Kenny Brown, the only one of my high school classmates who shared my admiration for Jack Kerouac and Charles Bukowski. Kenny had sought the book out after reading a profile of Fred Exley that appeared in the arts section of Newsday. The interview had taken place at the Lion’s Head Tavern on Christopher Street in the West Village, which the reporter mentioned was one of Exley’s favorite haunts, and one day in the summer of 1970, Kenny and I piled into his old Ford Falcon and drove into the city from Long Island to see if we could catch a glimpse of our new literary idol. But no such luck—when we asked the bartender if he expected Exley to stop in for a drink, he informed us that “Ex” had retreated to his home upstate in Watertown for the rest of the summer. Alas, I never had the pleasure of shaking his hand or buying him a shot of whiskey, but A Fan’s Notes has provided me with no end of pleasure through the years.

Long before the current craze for autofiction, Exley billed A Fan’s Notes as a “fictionalized memoir,” and when I first read it I was blown away by its harrowing but hysterically funny portrait of an alcoholic writer facing up to the fact that he’d been fated to watch from the sidelines while others—like his college classmate (and star football player) Frank Gifford—cashed in on the American Dream. Exley’s gift for turning the disasters of his life into stories that were simultaneously sad and side-splittingly funny was pure genius, and I’ve often described the experience of reading A Fan’s Notes as equivalent to making the Stations of the Cross high on laughing gas.

Strangely, I was lucky not to have started out, as most editors have, as an editorial assistant. I had the time to discover and hone my own taste with vast and indiscriminate, free-range reading.

GH: Steelwork was a revelation to me as well on multiple levels. For one thing, the fact that a serious writer of Sorrentino’s caliber had sprung from my own native asphalt was a shock. (I was such a snobby postgraduate asshole in those days about the neighborhood.) Not only that, Gil had captured with accuracy, and the true artist’s touch, the people I’d grown up with and the bars, churches, schools, diners, movie theaters, pool halls and bowling alleys I’d frequented. I’ve read pretty much everything he wrote, and I even got to interview him, in Bay Ridge, where he’d returned (Ulysses-like? Antaeus-like?) after many years out at Stanford, for a profile-cum-critical appreciation I wrote for Bookforum. He struck me as a genuine neighborhood guy who just happened to be a genius.

A Fan’s Notes hit home with me because it was such an acute portrait of the identity struggles that sad young literary men experience once they are ejected from their cozy collegiate cocoons into a world that doesn’t seem to give a rat’s ass about the things they cared so deeply about. That it concerned Frank Gifford and the football Giants really resonated with me as well, because some of the best times I ever had with my father were spent watching the Giants on the tube in the early sixties, when they were really good. I’m sure the old man must have been watching in 1960 when Eagles linebacker Chuck Bednarik sent Gifford to the hospital with a vicious but fair tackle that remains legendary.

I feel our time may be running out, so I suggest that we do what you might call lightning rounds, borrowing a format from Joe Brainard’s wonderful book, I Remember.

Here goes: I remember the excitement of reading Gordon Lish’s Esquire (Raymond Carver!), Ted Solotaroff’s New American Review, and Charles Newman’s TriQuarterly. I remember making the grisly rounds of “college graduate” job interviews in Manhattan while carrying a copy of Nabokov’s Ada to read during down time. I remember being guided in my taste and reading choices by the Times Book Review, so brilliantly edited by John Leonard in those days—including Wilfrid Sheed’s unmissable “The Good Word” column. I remember reading Ken Gangemi’s oddball little masterpiece Olt and trying to emulate its hero’s program of aestheticizing the experiences of everyday life for a couple of months before giving it up. And I remember being stoned a good part of the time, a condition that seemed entirely in sync with the effect that the mind-bending fiction we favored also had on our brains.

PK: Okay, I’m game. Like you, I loved Joe Brainard’s memoir. I remember with delight the 1974 National Book Awards ceremony, at which Professor Irwin Corey, the double-talking comic, showed up in place of Thomas Pynchon and accepted the award for Gravity’s Rainbow with a gobbledygook speech that was pure postmodernist cheek.

I remember being more intrigued by the imaginary baseball games played by J. Henry Waugh in Robert Coover’s The Universal Baseball Association than I ever was by Tom Seaver and the Miracle Mets.

I remember scoring a signed first edition of Stanley Elkin’s comic masterpiece, The Dick Gibson Show, for only two dollars at a used book store on First Avenue in midtown—arguably the funniest book to come out of the seventies, and unrivaled since then (although Sam Lipsyte’s recent novel Hark gives Elkin a run for his shekels).

I remember being awed by the macabre exuberance of Tlooth by Harry Mathews, which opens with a baseball game being played in a Siberian prison camp by teams that call themselves “The Defective Baptists” and “The Fideists.” As a seminary dropout and lapsed Catholic, I was half-tempted to order myself a customized baseball jersey that said, “Defective Papist,” but I stifled the urge—I had too many nuns and priests in the family, and I doubt they’d have taken it kindly.

I remember Ron Sukenick’s experimental novel 98.6, in which a group of back-to-Earth commune types rebel against what Sukenick, with uncanny prescience, labels “The Dynasty of a Million Lies.” Sound familiar?

I remember that the staff at the Gotham Book Mart were such fans of Jaimy Gordon’s debut novel, the baroque fantasy, Shamp of the City-Solo, that for many months they displayed it on the front counter, right next to the cash register, where I passed it by on quite a few occasions before the quirky title finally tempted me to pick it up. And guess what? The Gotham folks were no slouches at recognizing a future “cult classic” when they saw one.

And, finally, I remember how eagerly I awaited each new novel by Don DeLillo and Thomas Pynchon—as I still do to this day, nearly five decades later.

GH: You know, if it wasn’t for the Jaimy Gordon novel you mention, which stumped me, I might entertain the notion that we are actually the same person. All the other books and authors you recall so fondly are very much “front of mind” for me as well. (I remember, from the delightful Tlooth, Dr. King Dri, the “Philosopher-Dentist,” who treated ailing teeth by performing a sort of New Age psychotherapy on each individual tooth. And almost hurting myself with laughter while reading The Dick Gibson Show. )

Well old pal, thanks for the memories. We were very lucky to have intersected with such great writing at a time in our reading lives when we were most open and adventurous. I really do believe that it is time for some smart critic to take in the fiction of the seventies afresh and do it justice.

PK: And I’d agree, my friend—we need a next-gen Jerome Klinkowitz to give the decade its due. Let’s hope that some adventurous soul out there will take up the challenge.

_____________________________________

Idiot Wind, by Peter Kaldheim, is available from Canongate.