From Hitchhiking the Sahara (and Storing Hash in the Garage) to Co-Founding MTV and Running Viacom

Terry McDonell Talks to Tom Freston, Author of Unplugged: Adventures from MTV to Timbuktu

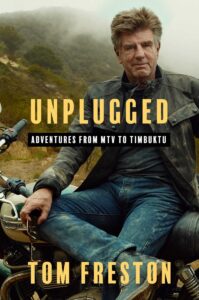

Unplugged: From MTV to Timbuktu begins on a hot Tuesday afternoon in 2006 in Tom Freston’s fifty-second floor office above Times Square, where he had run the entertainment giant Viacom until being abruptly fired less than twenty-four hours earlier by the then eighty-three-year-old Sumner Redstone in his Beverly Hills living room where huge fish tanks lined the walls. “It was like I was being taken out in an aquarium, harpooned by a mad Captain Ahab,” Freston writes in a rollicking, ironic voice that never lets up. Imagine a CEO memoir that rocks. “A brilliant business book wrapped inside of a wild adventure story,” blurbed Elon Musk biographer Walter Isaacson, who righteously never blurbs. Many rules are broken.

Freston was a cool suburban kid whose college and post-MBA choices to bartend and travel (across the US, around the Caribbean) lit his fuse. Hitchhiking the Sahara with a girlfriend built confidence. Extended stays in India and Afghanistan (a mix of competence and mischief) led to entrepreneurship. His creation of Hindu Kush, a clothing-export business based in India/Afghanistan reads like a case study in improvised ingenuity—with 250 pounds of hash in the garage (hash or hashish appear 48 times). It had sales in the millions over eight years but “vaporized like Ozymandias in Shelley’s poem.” Freston was thirty-three, deep in debt, and back in New York City when he got hired as the marketing guy at a start-up that would become MTV.

This is where Unplugged lifts off into the rock-and-roll stratosphere—an over-the-top, front-row, backstage, behind-the-velvet-ropes account of cultural transformation as Freston steps into ever-larger roles and responsibilities. He embraces leadership as opportunity, operating with artistic audacity and helping redefine youth culture. “What a ride,” as Freston is too cool to write—and what a read.

Freston’s clean-spirited rise to the C-suite feels discovered rather than engineered. He emerges as both storyteller and interpreter of experience, someone for whom travel is not escape but education, and leadership is an extension of close observation. His creative risk-taking and cultural fluency shape him into one of the media industry’s most influential executives.

Freston’s life is a compounding narrative of embracing uncertainty, following passions, and allowing seemingly disparate experiences to converge into a distinctive leadership philosophy. Unplugged ultimately argues that nontraditional choices, global curiosity, and openness to unexpected opportunity can lead to extraordinary professional and personal fulfillment.

The final proof is scale: guided by entrepreneurial instinct and cultural intelligence, Freston helps build a worldwide, multibillion-dollar media powerhouse spanning MTV, Nickelodeon, Comedy Central, VH1, and more—culminating in his tenure as CEO of both MTV Networks and Viacom.

Embarrassed to be leaving his Viacom office for the last time Freston takes the express elevator to the lobby to find more than a thousand employees gathered spontaneously to cheer him out, chanting his name or “Fuck Sumner!” If you were friends with Freston then (full disclosure: guilty) you heard about the hero’s sendoff almost immediately. There was so much good will across the media landscape that his firing from Viacom was transformed into a parable of resilience and discovery.

At large again and headed for the Jaipur Literary Festival, he’s got a lot to answer for.

*

Terry McDonell: Unplugged is a memoir but also a kind of hipster intellectual history of media over the last 40 years. Reading subhed, Adventures from MTV to Timbuktu, it strikes me that those adventures—traveling the world, meeting genuinely crazy expats, clandestine border crossings, a bit of smuggling, whatever—prepared you for uncanny success in corporate America.

Tom Freston: Asia was a perfect place to learn humility.

TM: Humility?

TF: That’s what’s lacking in the entertainment business, especially when you get to the higher levels. Looking back, I was fortunate to spend time in 1970s India, which was an assault on the senses in every way. You really got a sense of your insignificance. You’d be humbled just to make it through the day.

TM: You write that you gained confidence “operating low to the ground in treacherous, overwhelming places.”

TF: Especially taking risks. Perfect training for running a very eccentric, left-of-center media company in the eighties and nineties.

TM: I think the flash of MTV could be so blinding it distracted people from what was at the heart of what you were doing, which was extremely shrewd marketing and creative programming.

TF: We made it look chaotic on purpose. Underneath it all, there was a very clear methodology. We were in a midtown Manhattan office building, but we wanted to give MTV the personality of some kind of downtown, underground, hipster thing. Video clubs were starting, and the downtown art scene was in full swing. We got Basquiat and Warhol to get involved and do art breaks for us to give it a certain kind of quirky personality.

We made it look chaotic on purpose. Underneath it all, there was a very clear methodology. We were in a midtown Manhattan office building…

TM: And it worked for decades.

TF: We knew what we wanted to do and we learned how to maintain some level of coolness as we evolved, as talented people passed through and new ones arrived

TM: But it was always rock and roll so it could get wild, right? Like when you would Wayne places. Tell us about Wayneing.

TF: Wayneing was like saloon fighting in John Wayne movies. The first time was at Gurney’s Inn in Montauk at a staff retreat when our brand new corporate overlords helicoptered in to let us know that 1.) They weren’t going to pay off our stock options which they owed us; and 2.) We would be under some new kind of cost control regime. There was no mention whatsoever—or congratulations for us—of the great job we’d done in creating brand new businesses or any allusion to some kind of great future they saw for us. When they left, we went to the bar at noon, started drinking tequila and wound up throwing glasses, tipping over fish tanks and hurling palm trees.

TM: Like a bunch of Keith Moons, I guess.

TF: We Wayned a few places.

TM: Unplugged is full of crazy stuff like that and I think the subtext is that you could pretty much do whatever you wanted at MTV if the bottom line was growing—you could invade Carthage if you kept the strong box room full.

TF: There were only two rules. Make the bottom line and no frontal nudity.

TM: I am thinking about the MTV awards which you describe as “the usual cast of artists, celebrities, and criminals.”

TF: Yes, it was a rare assemblage. We tried to put together the good, the bad, and the smart and the stupid all in one spot.

TM: I’m talking about the writing, the preciseness of it. You describe Burma as “the crazy uncle of Southeast Asia, a country run by generals and fortune tellers.”

TF: I fell in love with Burma. Fortune tellers and soothsayers.

TM: That doesn’t sound like business writing, which the Wall Street Journal says Unplugged is, calling it a “CEO Memoir.” You also write Sumner Redstone’s memos come at you “like bomb threats,” and another executive is made to “walk the CEO plank.” Where does that come from?

TF: It just comes, I don’t know, inside my brain, thinking about business.

TM: You also write: “You work successfully at one place too long and your radar can dim. After fighting off so many lions and tigers, you may not notice a weasel sneaking up on you.” There’s a lot going on in those two sentences.

TF: You know, you don’t see the little weasels coming, and there are a lot of weasels in the media business. We even called ourselves weasels but there were weasels crawling up our backs and we were too busy to notice.

TM: Jon Stewart, among many of your fans, pointed to the humor in Unplugged; and it is hilarious, but it’s also extremely kind. I’m wondering if you were conscious of that kindness to the people that you write about.

TF: I could have been a little more ruthless, but I didn’t see the point of it really.

TM: You even write that you might be a little bit unfair to Philippe Dauman who succeeded you at Viacom, but that you were fated to be enemies from the beginning when he was Sumner’s estate planner and Summer was saying he was never going to die.

TF: It was a job predicated on theocraticals.

TM: You write it was “like listing which jewels and horses should be sealed up in the tomb with the Pharaoh’s sarcophagus.” I point this out because I admire the voice in the writing.

TF: Well, I did point out the deficiencies of a few, uh, a few individuals.

TM: You give Sumner his due as a cable entrepreneur, then he’s asking you to take him and his girlfriend to sex shows in Bangkok, and then he’s firing you.

TF: He fires me and goes on to live in infamy as a man who’s probably spent more on commercial sex than any human being who’s ever walked the Earth, $150 million.

TM: You report that in the book.

TF: Sumner wound up with a whole squad of comfort women servicing his every need at ninety-one years old and saying he had sex three times a day and all he did was eat steak. Two of these women made so much money they founded their own private charities.

TM And Sumner got to fire Tom Cruise.

TF: For a moment, until I had reminded him that Tom Cruise was the star of some of our movies, but he didn’t work for us.

TM: Which pissed him off.

TF: I should have seen it coming.

TM: You note in a couple places that most really big deals get made, not because of rigorous analysis of synergies or return on investment thinking, but rather driven by ego, vanity, revenge or some twisted combination of not necessarily admirable motives.

TF: We see a perfect example of that today with Netflix and Paramount going after Warner Brothers with bids that make no economic sense. I remember when Sumner bought Paramount, it was for $5 billion or so. Now they’re talking a hundred billion dollars and it’s going to go up and up. I don’t mean to be too dystopian, but there’s nothing in it for us consumers.

We see a perfect example of that today with Netflix and Paramount going after Warner Brothers with bids that make no economic sense.

TM: Do you miss having one of those jobs?

TF: I miss the plane, and most people who got fired from a job that comes with a plane will tell you the same thing.

TM: You write about dividing up Viacom and flipping a coin with Less Moonves to see who gets the best plane.

TF: That was a good flip because we had two jets, both Global Expresses, but one was brand new with a five-year service contract. The other, they told us, was the 14th one ever made, which of course made me think that it was really the 13th. It was one flip do or die, and Les honored the flip and took the bad plane.

TM: A through-line in Unplugged is why it’s important to see the world and find some humility within globalism.

TF: I know it sounds like jargon, but a lack of humility still strikes me as very offensive and a telling sign of an unhealthy culture.

TM: It occurs to me that you might have more to say about that.

TF: Well, I thought I did have a lot to say, but my editor told me “you’re not Barbara Streisand (who had just published a 970 page memoir), we’ve got to winnow your 800 pages down to 300 or so.”

TM: I heard that Simon and Schuster asked you for more, actually.

TF: That was after I cut it. And now they may want a sequel, but we’ll see what happens.

TM: Are you surprised by the reaction you’re getting? I’ve been looking at all the press and can’t find a negative word.

TF: When I started, as someone with imposter syndromeI by the way, I was thinking, do I even do this? Put myself out there? Now I’ve got a file of notes from credible people.

TM: So, you were nervous?

TF: You don’t want to come out and lay an egg.

______________________

Tom Freston’s Unplugged: Adventures from MTV to Timbuktu is available now from Gallery Books.

Terry McDonell

Terry McDonell has published widely as a journalist, top-edited a number of magazines, and was elected to the American Society of Magazine Editors Hall of Fame in 2012. He is the author of The Accidental Life: A Editor's Notes on Writing and Writers and Irma: The Education of a Mother’s Son. He is president emeritus of the Paris Review Foundation and co-founder of Literary Hub. TerryMcDonell.com