From High School to Vietnam, Waiting for the Fight to Begin

Echo Company Waits for War, on the Eve of the Tet Offensive

The newly arrived soldiers celebrate their first night in-country by filling sandbags and fall asleep on cement floors under canvas roofs stretched over makeshift wooden walls. Stan Parker drifts off thinking of home, of nights back home when he pulled into the Blue Top Drive-In with Tom Gervais, without much of a care in the world. He wonders about Gervais’s warning: Stay away, Boots. Why would he write such a thing? He thinks of his mother and wishes he could speak to her, ask her if she is proud of him yet. He wonders when he’ll discover just what Gervais meant.

*

The next morning, December 14, Echo Company is transported northwest, through Saigon, to a place called Cu Chi, located in a thirty-square-kilometer region of expansive enemy fortifications that US commanders call the Iron Triangle.

Since the end of World War II, the Cu Chi area has been a haven for guerrilla fighters. Recon’s job, Stan learns, will be to hunt and engage these fighters.

When he looks around Cu Chi, he sees acres of forest braided with creeks, a shaded, pleasant place. A year earlier, the US Army’s 25th Division set up their base, completely unaware of the danger living below them, literally under their feet.

They had located atop a nerve center of the North Vietnamese Army and its guerrilla cadre, the Viet Cong. Miles of tunnels snake underground all the way to the city limits of Saigon. As the war has grown in intensity, the guerrillas have built hospitals and kitchens underground and devised an ingenious system that pipes the cooking smoke aboveground. The hidden piping might extend fifty feet on a horizontal plane and finally emerge on the forest floor, with the chimney opening screened by woven leaves. To anyone passing by, the emerging mist looks not like smoke but resembles a marvel of morning sunlight. The tunnels’ interior doors lead farther down into protected dwelling spaces. Some of the tunnels lead to a river, where, by a clever feat of engineering, a soldier can enter and exit the complex through an underwater opening. The tunnels are part of a large underground city with infirmaries, dormitories, and armories.

Dotted around the Cu Chi area are dozens of “spider holes,” fighting positions dug by the Viet Cong close to the myriad tunnel entrances. A fighter can hide in a spider hole and wait in ambush, fire off a few rounds, and slip undetected through the tunnel’s camouflaged entrance.

You could crawl through these tunnels—measuring maybe three feet high and two feet wide—and eventually pop out of a trapdoor in sight of a busy street in Saigon, pull yourself up through the hole, replace the camouflaged lid capped with leaves and twigs, tamp it back in place, brush off your clothes, and walk into town into the flow of traffic and become one of millions of South Vietnamese living in Saigon. That, in fact, is precisely how the North Vietnamese Army has been moving into position to attack the Americans in a planned early-winter operation, scheduled for the Tet New Year.

Chiefly, the NVA are using the 600-mile-long Ho Chi Minh Trail that snakes through Laos and Cambodia; once they get close to the cities in South Vietnam, they hide in places like the tunnels at Cu Chi, which had been built under the command of Ho Chi Minh in the late 1940s. This means that by the time Stan Parker and the Recon Platoon arrive, the Viet Cong know these Cu Chi woods as intimately as Tom Sawyer knew the caves of Hannibal, Missouri.

By December 15, Stan and his fellow soldiers settle into new quarters, struggling to acclimate to the tropical climate. They have been warned about the dangers of sun exposure and instructed to acclimate by getting a “suntan” (read, “sunburn”). After a week of filling sandbags, Stan longs to go on a patrol. He expresses some of his frustration of garrison life in letters to his high school girlfriend, Maureen.

“I have a few extra minutes,” he writes, “so I thought I would drop you a few lines. A lot has happened since I wrote to you last”:

Around the end of the month, we’re going to join up with the 101st’s 1st Brigade and with 3rd Brigade and the whole 101st Airborne Division is going up on the Cambodian border and kick some ass. We’re going to end this war.

General Westmoreland himself said, “Give me the 101st Airborne Division and I’ll give you Vietnam.” Besides, this is an election year and something has to change about this war.

Have a real good tan now, real nice weather for getting a tan over here, but sure as hell gets cold over here at night. Oh shit does it get cold, oh shit does it get hot . . .

I never did tell you thank you for going out with me when I was home . . .

Well, I’ve got to go now and do what I was sent here to do (get a good suntan) . . . Tell your mom hi for me, love you, Stan.

Finally, after two weeks, they start patrolling and scouting for VC fighters. Stan is surprised by the dryness of the vegetation; he had expected to be in thick, wet jungle. The dust he kicks is red, like paprika, and tastes oily. He passes straw and bamboo huts and smells what he guesses is fish cooking. He soon comes to learn that the smell is nuoc mam, a fish oil, and an essential flavoring in food. The patrols are an assault on his senses, while his heart hammers in his chest.

They patrol a place they call Hobo Woods and through a French-owned rubber plantation called Filhol. They walk in single file, as trained, separated by about fifteen feet; this way, if they are attacked, they’re not bunched in groups and are slightly less vulnerable to mass casualty. The lead soldier is the point man and the guy behind him is called the slack position (as in, he’s “walking slack”). The slack guy’s job is to keep an eye out for anything the point man might have missed—literally, take up the slack. Most days, a Huey will land and pick them up from their patrol, before dark, and take them back to Cu Chi. One night, Viet Cong soldiers probe the camp’s perimeter and in the 30-minute fight that ensues, 30 Viet Cong soldiers are killed and two taken as prisoners.

Through all of this, Stan still hasn’t fired his weapon. “We were itching for something to happen,” he writes to his father.

In the minds of the men of the platoon, the Viet Cong and NVA are wily, elusive opponents, quick as wraiths. They view them as able adversaries, but feel they are cowards because they’ve heard they rarely stand their ground in a fight. Almost as soon as battle begins, they melt back into earth and trees.

They’ve also heard that the VC and NVA are masters of devising ways to maim, having perfected all manner of booby traps, often made of sharpened bamboo stakes called punji sticks, smeared with human excrement, mounted on swinging boards, and triggered by an unsuspecting footfall on a trip wire. The stakes can come swooping down from a tree branch or fly up from the ground, impaling the soldier in his path.

There are trapdoor booby traps that, when you step on them, flip up and drop you down into a grave-like hole lined with punji sticks. There are spiked booby traps strung in trees designed to drop down and target a man’s genitals and puncture arteries. The uses of sharpened bamboo go on and on, the ingenious answer of a poor people to a richer country’s superior technology and firepower.

“Come on, do something!” Stan writes to his father. “Shoot at us!”

Little does Stan know that beneath them, enemy soldiers are gathering and waiting to do just that.

__________________________________

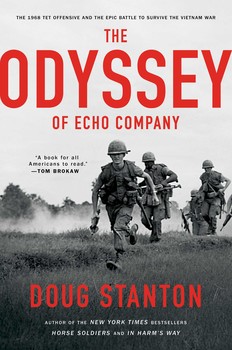

From The Odyssey of Echo Company by Doug Stanton, courtesy Scribner. Copyright 2017 by Doug Stanton. Image via Wikimedia Commons.