From Gatsby to Giovanni's Room, the Stories Behind 5 American Classics

Jake Grogan on the Origins of 5 Great Books

The Great Gatsby, F. Scott Fitzgerald

“While I have every hope and plan of finishing my novel in June, you know how those things often come out, and even if it takes me ten times that long I cannot let it go out unless it has the very best I’m capable of in it, or even, as I feel sometimes, something better than I’m capable of.” Fitzgerald wrote this in 1924 to his editor, Max Perkins. Fitzgerald’s very best yielded a commercial failure, at least in the immediate sense, but it wasn’t long before readers caught on to the novel’s brilliance.

Fitzgerald’s This Side of Paradise offered him the fame and access necessary to achieve good standing with the moneyed class of the Roarin’ Twenties—whose parties inspired the ones hosted by Gatsby in his West Egg mansion. The origins of that mansion are cloudy, though a 2011 article in the Los Angeles Times suggests that it was based on Land’s End, a Gold Coast Mansion where Fitzgerald had once attended a party. The origins of Nick Carraway and Jay Gatsby, however, are much clearer, as Fitzgerald writes himself into both. Nick was an Ivy-educated man, while Gatsby met the love of his life while stationed far from home in the military. Both were defining characteristics of Fitzgerald’s life, as he himself writes on his Ivy League education: “My new novel appears in late March: The Great Gatsby. It represents about a year’s work and I think it’s about ten years better than anything I’ve done. All my harsh smartness has been kept ruthlessly out of it—it’s the greatest weakness in my work, distracting and disfiguring it even when it calls up an isolated sardonic laugh.” Fitzgerald met Zelda, his wife, while stationed in Camp Sheridan outside Montgomery, Alabama. Zelda was a debutante born into wealth, and Fitzgerald idolized the way that she lived; like Gatsby, he did much to prove himself worthy of her company.

In her Careless People: Murder, Mayhem and the Invention of ‘The Great Gatsby,’ Sarah Churchwell claims that the two murder victims in the novel were inspired by the Halls-Mills Case of the early 1920s, which saw the murder of a priest and his mistress garner nationwide attention. On how she made the connection, Churchwell tells Signature, “It’s interesting the way that some people don’t see the Halls-Mills case as paralleling Gatsby very satisfactorily because the details don’t match up, but for me . . . the underlying themes are there. And so one of the things I was hoping was to suggest that all of the themes from Gatsby were in the air as Fitzgerald was writing. Not necessarily that it was a one-to-one correspondence with Hall-Mills, but Hall-Mills is representative of the kinds of stories that were around. It’s not that I think that Fitzgerald was transcribing this case into his novel—that would be foolish—but rather that the case has these echoes of the deep themes of Gatsby. So for example, class resentment and social climbing . . . that there’s actually a character in both stories who makes up a romantic past and a more aristocratic past. That this story about social climbing and class resentment is specifically about a woman who is seen as using an affair as a way to gain access to a better quality of life.”

Giovanni’s Room, James Baldwin

It was in 1956 when James Baldwin, an African-American author with a history of writing about black characters, penned a novel about a gay white man in Paris, France. “I certainly could not possibly have—not at that point in my life—handled the other great weight,” he said in a 1984 interview with the Paris Review. “The ‘Negro problem.’ The sexual-moral light was a hard thing to deal with. I could not handle both propositions in the same book. There was no room for it. I might do it differently today, but then, to have a black presence in the book at that moment, and in Paris, would have been quite beyond my powers.”

Baldwin, who cites his time preaching from ages 14 to 17 as a major reason why he got into writing, was no stranger to tragedy. His father died when he was young, and his best friend committed suicide by jumping off the George Washington Bridge. Worn down by the torment he had experienced in New York City, Baldwin moved to Paris, where he himself almost succumbed to sickness. He luckily found care and hospitality in a place that rarely afforded such things to black men, giving him the opportunity to hear about Lucien Carr. Says Baldwin, “David is the first person I thought of, but that’s due to a peculiar case involving a boy named Lucien Carr, who murdered somebody. He was known to some of the people I knew—I didn’t know him personally. But I was fascinated by the trial, which also involved a wealthy playboy and his wife in high-level society.”

Lucien Carr inspired Giovanni, the man who has relations with David on the night before his execution. David, on the other hand, was likely inspired by Baldwin himself. Upon first moving to Paris, he fell in love with a Swiss man named Lucien Happersberger, with whom he lived for a brief time. His inability to depict a man who was both black and gay could be a nod to his real-life trouble with that duality, which made him a marginalized figure in American society. Regardless, Baldwin was way ahead of his time, as his depiction of a gay main character came well before the gay liberation movement.

The Color Purple, Alice Walker

“My mother planted so many flowers around our shack that it disappeared as a shack and became . . . just an amazing place,” said Alice Walker in a 2013 interview with the Huffington Post. “So my sense of poverty was always seen through the screen of incredible ingenuity and artistic power.” Walker was born the daughter of two sharecroppers in Eatonton, Georgia, in the year 1944, when racism was very much the prevailing mentality of the deep American South. When she boarded a bus to leave for Spelman College in Atlanta in 1961, a white woman requested that the bus driver force her to the back of the bus, and he obliged. “I can refuse and sit in the front and get arrested in this little town,” she recalled, “or I can stay on the bus, get to Atlanta, check into my college and immediately join the movement for civil rights.”

Walker’s repeated encounters with racism reflected the experiences of many individuals she knew, but were seldom represented in anything that she had read. “In most literature, the lives of the people I knew did not exist. My mother for instance was, you know, nowhere in literature. She was all over my heart, so why shouldn’t she be in literature? People like my parents and my grandparents, the stories that I heard about their younger years were riveting. I started writing this novel longing to hear their speech. I was so determined to give them a voice, because if you deny people their own voice, there’s no way to ever know who they were. And so they are erased.”Frank Herbert,

Walker interviewed and transcribed the testimonies of sharecroppers facing eviction, using their stories and the stories of those she’d known growing up to write The Color Purple, her Pulitzer Prize–winning novel. “What I would like for people to understand when they read The Color Purple is that there are all of these terrible things that can actually happen to us, and yet life is so incredibly magical, abundant and present that we can still be very happy.”

Dune, Frank Herbert

Taken by the massive sand dunes in Florence, Oregon, Frank Herbert once wrote to his agent that they could “swallow whole cities, lakes, rivers and highways.” The US Department of Agriculture was attempting to provide integrity to the dune structure by planting large patches of grass throughout, inspiring an article that Herbert wrote, “They Stopped the Moving Sands.” The article was never completed but inspired him to continue researching the subject, as evidenced in his three-part series Dune World, which was published in the science fiction magazine Analog. The following year, in 1965, Herbert wrote a five-part series titled The Prophet of Dune, published in the same magazine. He tried to get an expanded and revised version of the series published as one novel, but the idea was soundly rejected across the industry. Only Chilton Books, better known for printing manuals, agreed to take it on. In his dedication, Herbert wrote, “To the people whose labors go beyond ideas into the realm of ‘real materials’—to dry-land ecologists, wherever they may be, in whatever time they work, this effort at prediction is dedicated in humanity and admiration.”

The Bell Jar, Sylvia Plath

Originally published under the pseudonym “Victoria Lucas” in 1963, The Bell Jar was Sylvia Plath’s first and only novel, published one month before she committed suicide. She began writing the novel in 1961, according to her husband, directly after publishing her collection of poetry titled The Colossus. Plath separated from her husband and moved to a smaller apartment, “giving her time and place to work uninterruptedly. Then at top speed and with very little revision from start to finish she wrote The Bell Jar,” he said.

The novel, which at one point was titled “Diary of a Suicide,” was semi-autobiographical; names and places reflect real people and places in Plath’s own life and Esther, the protagonist, experiences a descent into depression much like Plath did in her own life.

__________________________________

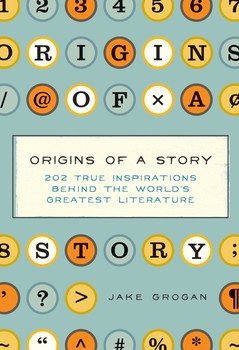

From Origins of a Story, by Jake Grogan, courtesy Simon & Schuster.

Jake Grogan

Jake Grogan is the author of Origins of a Story.