From Exobiology and Geology to... Writing Fiction?

Linda Rui Feng on Writing as an Act of Telepathy

In 1986, the previous time Halley’s Comet approached earth, I was an elementary school student living with my uncle’s three-generation family in Shanghai. Our Soviet-style building had balconies that faced towards the shipyards of the Huangpu River as it emptied into the sea. The ships coming and going were out of sight, but at night, sleeping in the room with my grandma and cousin, I sometimes woke up to the sounds of baritone ship horn from beyond the balcony. The bellows were unhurried, far-reaching, and, unlike anything else, announced forcefully the presence of an Elsewhere.

That year the comet was all but impossible to see from our latitude, but it was around then that I took to the balcony every night in order to replicate what I considered a scientific experiment. By chance I’d scavenged a book nestled in my uncle’s bookshelf that described how a man successfully communicated with extraterrestrials using what was called xinling ganying. I’d never encountered the phrase before, but could parse the word-pair to impart their meaning: “heart” plus “remote response.” It was my first encounter—on the page—with the phrase mental telepathy. According to that book, this man eventually received his rejoinder from outer space; he felt something like a jolt inside his chest when the otherworldly intelligence told him that they had been the “original inhabitants of the earth.”

So I decided to spew forth my own telepathic thoughts through the air and waited for interception over the vast distances. I don’t remember what thought-messages I emitted to our galactic neighbors, only that I didn’t tell anyone in my family of my telepathic attempts, because I couldn’t yet explain why the idea was so compelling to me.

*

If exobiology first drew me to astronomy and physics, it was the earth sciences that led me eventually to writing.

Throughout my college years, I took internships at national labs and research centers, where I learned to cut up mylar film, bake high-temp superconductor samples, and feed data into computer models that simulated tropospheric chemistry. I had been lucky, too, because at each of these stints, members of the scientific world encouraged and welcomed me, and I hopped from one natural science program to another until I settled down, toward the end of college, in the small and congenial department of earth sciences. My undergrad thesis advisor, Dick Holland, was a geochemist, and when I mentioned applying to graduate school, he immediately helped me come up with a list of prospective schools.

But even as I planned for a career I knew to be both meaningful and respectable for an immigrant, I also hesitated. The end results of science excited me, but I also understood that conducting day-to-day science was different, and I was—just maybe—looking for something else.

The summer before I was to graduate, I joined a field trip with Dick’s research group which took us to an area in Ontario, deep in the Canadian Shield. Having spent all my time in classrooms and labs, I’d never before clambered around on bedrock or held a hand lens over the surface of a rock to scrutinize its grain size. Fortunately, on the trip Dick never missed an opportunity to pull over the van and offer roadside geology lessons.

If exobiology first drew me to astronomy and physics, it was the earth sciences that led me eventually to writing.

Standing in front of road cuts, he would point out folding patterns where you could see that sedimentary layers accumulated over millions of years were heated by the earth’s internal engine and bent into undulating patterns. A rock with constituent clasts of different sizes signaled that it was laid down not by rivers but by glaciers, which flowed very slowly but could readily mobilize bigger rocks, even boulders.

Whenever something unusual presented itself, Dick was fond of asking us, “What’s the story here?” to get us to reconstruct the process of transformation using verbs and causes and effects. I’d never heard a science professor use the s-word before, and it was exhilarating. I learned that rocks can be read as richly illustrated tomes for evidence of epic and even cataclysmic change, and that there was a particular logic to it if you looked carefully. Dick made sure I looked carefully.

At one point he lugged over a jagged piece of concrete and tried to get me to identify the “conglomerate,” then guffawed like a drunken teenager when I appeared suspicious. I loved the fact that human timescales, in units of months and years and maybe decades which we are most comfortable thinking and planning in, are minuscule by comparison in this geological timeline of events. This is what geologists call “deep time,” and I felt oddly at home with it.

We were headed to the Gowganda Formation, where the expanse of deeply storied rock, roughly half the age of the earth, lay exposed in all its Precambrian glory, a lithified snapshot of events that happened to landscapes and organisms on timescales beyond human reckoning. Dick’s research group was trying to understand the composition of earth’s ancient atmosphere, which, until 2.3 billion years ago, hardly had any oxygen. In that oxygen-deprived atmosphere, some boulders and large pebbles rolled around in either a lake or a sea and, weather-beaten, acquired a distinct outer shell. (I imagined shadows sweeping across the clasts, as the earth made its circuit around the sun time and again.)

Then an ice sheet covered over them and buried them underneath, and this mixture eventually hardened from earth’s heat into a type of rock geologists call “tillite,” and the boulders and pebbles became its constituent clasts. So the research group was working on whether what we see in the Gowganda Formation could help reconstruct the early earth’s pre-oxygenate atmosphere, an important prequel for life as we take for granted.

At the end of one of our last days in the field collecting samples, I happened to be alone at the site. As I took notes about the outcrop for my thesis, I found myself doing something unsanctioned by the scientific method.

I talked to the clasts. I singled out one of the eye-catching boulders, pink (rich in the mineral feldspar) bordered by a black (chlorite-rich) rim.

Hey you, I said to the clast through what I considered a form of human-rock telepathy. What was it like to be steeped in an atmosphere that would have suffocated us humans? How do your outer shells prove this?

Perhaps this was hubris, megalomania. This was certainly bad science. In a relaxed moment, unobserved by others, interspersed with scientific wonder, my approach to paleoclimatology was to hold an interview with a glacial tillite.

I had returned to my old habit, you see, of speaking to the remote and unreachable.

I didn’t know it yet, but this was to be my habit of speaking to my fictional characters, too, when left alone with them. When I was working on my first novel, which has four point-of-view characters in a braided narrative, I would ask each character questions and coax confidences from them. I sometimes even interrogated characters I’d killed off. (“Now that you are in a place that is beyond hope and despair,” I would begin.) Some days, of course, the characters are less forthcoming than others. When I struggled to figure out what a character is truly longing for, or how a backstory from her childhood shaped her imagination and fears, I even cajoled her to talk. (“Now look here—if you want your story to be told, you gotta throw me a bone.”)

At the end of that summer field trip to the Gowganda Formation, we brought back to campus rock samples of the clasts. One of Dick’s graduate students advised me on X-Ray fluorescence analysis and how to structure a thesis. The scientific details have faded from my memory, yet I can clearly recall pacing back and forth on the polished and beautifully exposed Gowganda outcrop with my head lowered, beckoning inanimate objects to surrender their secrets.

*

There is no point in this recollection where I can write, “and the rest is history,” for the choices I make between science and art, between atoms and stories, are as vacillating and tentative as they have ever been. Before Dick Holland passed away, I didn’t have the chance to tell him that, when he was teaching me field geology, he was also guiding me toward another career whose prospect at that time was as amorphous as the prospect of grad school was concrete.

Years later, as I began writing fiction in earnest, I found that I was drawn to stories of outsize time scales. I love writing about characters who try to make sense of the entanglement of time before their lives are set into motion, and those who struggle to imagine a world after them, without them. In one of the early versions of my novel, I wrote about a middle-aged Chinese father—Momo—who drives out of town in the American plains to spot Halley’s Comet. Because his young daughter lives halfway across the world, Momo shouts at the fuzzy blob barely visible at the horizon, asking the comet to greet Junie on its next return, when he himself would be long gone. Though I cut out this scene in a later draft, I like to think that something of its emotional weight became folded into the novel’s internal logic.

Writing, for me, is an attempt at telepathy, no less Herculean than trying to intercept inter-galactic messages. To the writer, the promise of seeing its sought-after consequence always seems remote, while the possibility of failure looms large. Yet as soon as you begin to undertake this seemingly futile task, something about your world—even just the fact of its limited circumference—snaps into place.

During the summer field trip with Dick, the most memorable thing he showed me was a sedimentary rock type called a dropstone. The specimen we saw was light colored with delicately and rhythmically spaced horizontal layers, nearly perfect, except at one spot, a small pointy stone is poised against the layers and makes a dent in the fine parallel pattern. What I learned of its chronology was something that I took with me from early adulthood to my thirties and now into my forties, as I try, still, to figure out what it is I write from: Year after year, a fine layer of clay is deposited at the bottom of a quiet lake or shallow sea, adding imperceptible thickness to the bed.

This one year, a piece of ice that happens to be ferrying a small pebble melts away, and the pebble sinks through the water column and lands at the lake bottom, making a small dent in it. Gradually, new accumulating layers of clay cover up the pebble, and over time its contour vanishes the way a pea disappears under a mattress. It is a minuscule event, infinitesimal in significance, except that you can see it, right there, and you, the late-arriving, oxygen-breathing earthling similarly infinitesimal in the grand scheme of things, you blink to hold it in your field of vision and think, This is the story—the story is here.

___________________________________________________

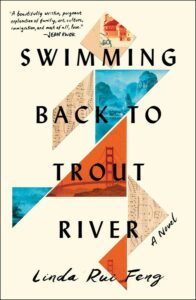

Excerpted from Swimming Back to Trout River by Linda Rui Feng. Copyright (c) 2021 by Linda Rui Feng. Used with permission of the publisher, Simon & Schuster. All rights reserved.

Linda Rui Feng

Born in Shanghai, Linda Rui Feng has lived in San Francisco, New York, and Toronto. She is a graduate of Harvard and Columbia Universities and is currently a professor of Chinese cultural history at the University of Toronto. She has been twice awarded a MacDowell Fellowship for her fiction, and her prose and poetry have appeared in journals such as The Fiddlehead, Kenyon Review Online, Santa Monica Review, and Washington Square Review. Swimming Back to Trout River is her first novel. Visit LindaRuiFeng.com to learn more.