From Aspiring Cartoonist to The New Yorker

Jake Goldwasser Takes Us on His Creative Journey

When I graduated college, in 2014, The New Yorker was still letting aspiring cartoonists come into the office to pitch their artwork. For a 21-year-old, the chance to sell cartoons alongside regular contributors was like a chance for a little leaguer to pinch-hit for the Yankees. I was exhilarated.

Every Tuesday morning, I sat in the Cartoon Lounge, a small conference room conducive to neither cartooning nor lounging, and awaited my turn with the editor, a brusque, wire-haired man who had been professionally passing judgment on gags for as long as I had been alive. My batch of eight was a drop in his bucket—more than a thousand a week—and the odds were slim. But the real prize was time with the cartoonists. In my weekly date with the pantheon, I had a rare opportunity to ask them about their processes, tools, and influences.

Eager to emulate them, I studied the backlog of cartoons, asked them what inks and nibs they used, and watched videos of them drawing to recreate the pace of their hand motions. I printed out cartoons and traced them. I became an expert in inks and papers. I spent a lot of my time in a parallel world of desert islands and therapy couches.

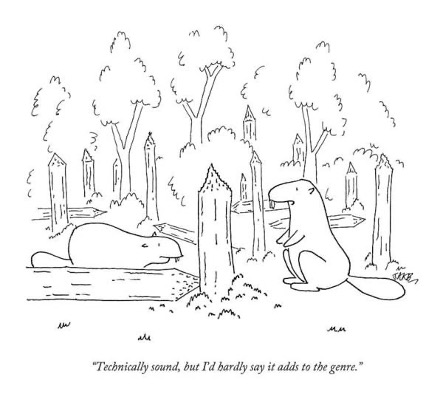

My research, however, wasn’t impressing the editor. The work I was producing was just what I had strived for—an emulation. It was stiff and lacked idiosyncrasy. “Technically sound,” he cautioned, “But I’d hardly say it adds to the genre.” Aha, I thought—that’s a caption. Transposing the scene, I drew one of the first cartoons I would go on to sell to the magazine.

Even back then, my clumsy illustration made me cringe. I could tell that my drawing ability wasn’t up to snuff, and I continued to study other artists’ work in the hopes of getting better. (Back to the old drawing board, as one classic cartoon advises.)

While the masters’ styles and processes varied widely, what I found they did share was a common mindset: an improvisational, meditative mode that governed the act of drawing. Artists like Liza Donnelly often make the whole cartoon in a single inky session, without a reference image, and have to produce several attempts to find one that works. This state is conveniently on display in YouTube process-videos that include cartoonists’ trance-like narrations as they draft—in them, not only can you watch their composition unfold, but you can also see their equanimity when, for example, the pencil tip snaps or the nib doesn’t cooperate. A real-time view into artists’ thought processes is a unique advantage of visual media—most writers wouldn’t dare put a camera on a poem’s or story’s gruesome revision process.

The editor teased me: “Do you know how many people have sold three and never published again?”Writers are sometimes encouraged, rather quaintly, to actually write out, longhand, a Shakespearean stanza so we can know what it feels like for genius—or at least really good writing—to flow through our fingertips. The rub here is that the experience of banging out a sonnet in ninety seconds on a MacBook bears almost no fidelity the experience of composing a sonnet, which even for Shakespeare must have been effortful and thought-intensive, the stuff of a creative flow state. What does it feel like for Terrance Hayes to write a sonnet? It’s a kind of interiority that isn’t fully communicable outside the controlled chaos of the poem itself. In cartoons, though, thought proceeds in lines, right before your eyes.

In my first year submitting to The New Yorker, I sold a couple of cartoons, but the specter of beginner’s luck was always at my back. The editor teased me: “Do you know how many people have sold three and never published again?”

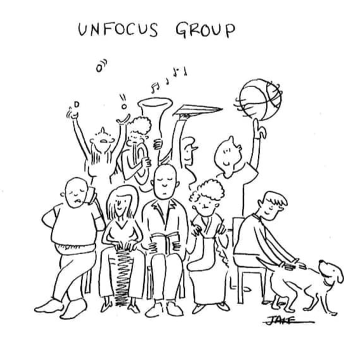

The single-panel cartoon is about as restrictive as a genre can be. Limited to a few square inches of illustration and a dozen words at most, it doesn’t lend itself naturally to self-exploration. (Graphic narrative, comics, and even comic strips are different stories—and some single-panel cartoonists are exceptions that prove the rule.) In a gag cartoon, there is always the pressure to snap to a punchline, which is why even the best cartoonists default to the same proven scenes and tropes. Frustrated by these constraints, I turned more and more to writing poetry to explore ideas and feelings. I became interested in how a medium enables (or fails to enable) self-expression. Sometimes this even came out in my cartoons:

Eventually the curse came true—I went years without selling another cartoon, and I felt so taxed by the rote labor of putting my weekly bundle together, I all but abandoned the craft.

In the low point of that dormant period, I listened to an interview with George Saunders about writing fiction. His advice, to my surprise, was not about point of view, structure, or the sentence but rather about the conscious experience of writing. It was guidance that sounded more like it came from the mouth of a Tibetan monk than an MFA.

“There’s a meter in my head [that] responds when I read prose,” he said. “The whole thing for me is to be reading my work as if I didn’t write it… And then all the time, another part of the mind is watching that meter, basically saying, what would a first-time reader be feeling right now? In or out, in or out?”

Saunders’ meta-cognitive take on craft brought me back to my early days as a cartoonist, discovering the role that attention played in a drawing practice. I thought about videos of cartoonists cultivating a sense of equipoise in the face of catastrophes like ink blobs and stray lines, proceeding with the image as though it were a meditation rather than an object. I thought about the white-out corrections and bristol-board patches that often adorned Roz Chast’s finishes, the digital process-reveal videos of Jeremy Nyugen, and how the elder cartoonists had all seemed to attain a certain level of comfort with blemish as a feature of the form. This was, after all, cartoon, not marble statuary.

Saunders’ advice inspired me to revisit drawing with a different mindset. I tape my paper to the board, I dip my fifty-cent nib into India ink, and I watch myself make shapes. An image emerges, or it doesn’t. Am I enjoying the shape of this elbow or this suitcase or this Shetland sheepdog? I try to make shapes that amuse me. I ask myself questions as I draw.

I’m trying to get into this mindset with poetry, too, but it’s harder. Language is so tangled with attention, it can be hard to tell the writing from the writing mind. It feels nearly impossible for me as a poet to cultivate a state of equanimity in relation to a poem that is so wrapped up in my sense of self.

Focus, in my practice, means getting a handle on that: monitoring, non-judgmentally, my conscious mind while writing. But, of course, that’s easier said than done.